Krivit Paper on Widom-Larsen LENR Theory Publishes in EPJC was last modified: February 7th, 2024 by sbkrivit

Feb 072024

Jan 5, 2024

By Steven B. Krivit

The first vacuum-vessel sector waiting in the assembly hall, Dec. 2021. The core of the reactor will be built from nine of these sectors.

Two years ago today, French nuclear authorities ordered a halt to assembly of the core of ITER, the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor. Neither the French regulators nor the ITER Organization publicly initially disclosed the shutdown. New Energy Times broke that story on Feb. 21, 2022.

The organization was unable to proceed with assembly of the massive vacuum-vessel sectors because of multiple fabrication and shipping defects. Ancillary construction on the site continued; however, assembly of the reactor core is an essential process of the critical-path for the project.

New Energy Times asked Laban Coblenz, the spokesman for the organization, for the earliest projected date for the installation of the repaired sectors. He did not reply.

Timeline entry posted on ITER Organization’s Web site, Dec. 2021

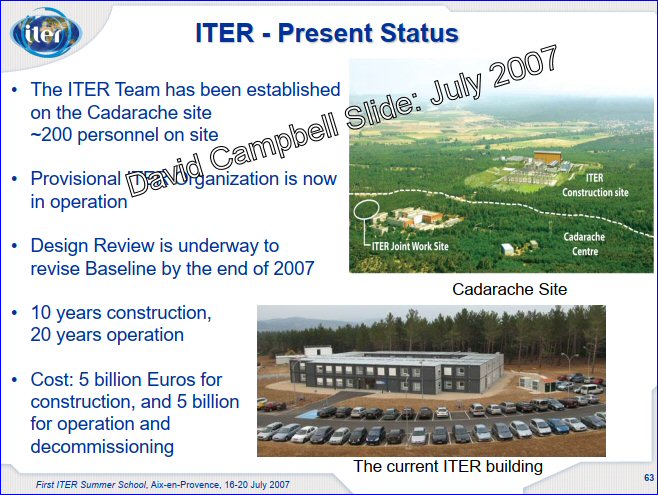

When the ITER project was approved by its international partners, the cost was estimated at €5 billion. But that value did not include most of the parts. In 2018, David Kramer of Physics Today broke the story that — as of 2018 — a more realistic estimate for the project was $65 billion (€59 billion).

Thanks to journalist Charles Notley for his excellent questions that led to this interview with a concise explanation of low-energy nuclear reaction research (LENRs). It’s a great starting place for people who are new to the subject.

“The Promise of Low Energy Nuclear Reactions” (Oct. 6, 2023)

To all LENR researchers and fans: Please enjoy the video of my ICCF-25 presentation on the Widom-Larsen theory and follow-up discussions. I hope you find my work informative.

PART 1: Introduction

PART 2: Krivit Presentation at ICCF-25

PART 3: Discussion with Konrad Czerski

PART 4: Discussion with Robert Greenyer

PART 5: Discussion with David Nagel

PART 6: Summary

Edmund Storms, the most vociferous critic of the Widom-Larsen theory, did not participate in the conference in-person. If he did participate remotely, he elected not to speak during the available time in the question-and-answer portion. I have addressed his previous statements in this article.

Dec. 29, 2023

By Steven B. Krivit

On Dec. 14, 2023, the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA) announced initiatives to research methods for enriching lithium in the lithium-6 isotope. Lithium enrichment at scale would be required to breed the tritium fuel that will be needed for commercial deuterium-tritium fusion reactors.

The UKAEA has funded four universities and one private company to find an effective way to produce the large quantities of enriched lithium that will be required in deuterium-tritium fusion reactors.

Two years ago, New Energy Times broke the story, explaining that, without a viable method to enrich lithium and without a sufficient tritium breeding rate, no fusion future will be possible. At the time, we were not aware of any active research program to develop a replacement for the environmentally hazardous COLEX lithium-enrichment process. The process has been banned in the United States since 1963.

Fusion advocates like Andrew Holland, the chief executive officer of the Washington, D.C.-based fusion advocacy group Fusion Industry Association, promote the idea of fusion as safe and harmless. In contrast, according to the U.S. National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), “when used as a target in a nuclear reactor, lithium-6 reacts with a neutron to produce tritium, the most important thermonuclear material for weapons.”

According to the NNSA, from 1954 to 1963 about 442 metric tons of enriched Li-6 were produced at the Y-12 plant in Oak Ridge, Tenn., for nuclear weapons use. NNSA states that it has no further need to enrich additional quantities of Li-6 and needs only to recycle its existing quantities of enriched lithium-6. Construction on a new processing plant — for recycling, not enrichment — broke ground on Oct. 19, 2023. In an Oct. 20, 2023, article in knoxnews.com, Gene Sievers, the Y-12 site manager, confirmed the danger of lithium enrichment.

“We are the nation’s steward of the stockpile of lithium,” Sievers, said. “We don’t go mine and then enrich and then use lithium. We recycle the lithium that we enriched decades ago, and it’s Y-12’s mission to be the careful stewards of that, so we don’t have to go back and engage again in that, what I will just say, chemically hazardous process.”

Earlier this year, the ITER organization explained the gravity of the fusion fuel situation: “Over the course of its scientific program, ITER will acquire and consume the totality of the world’s tritium inventory, which amounts to only a few dozen kilos. Developing solutions to breed large quantities of tritium is therefore a precondition for the development of industrial and commercial fusion reactors.”

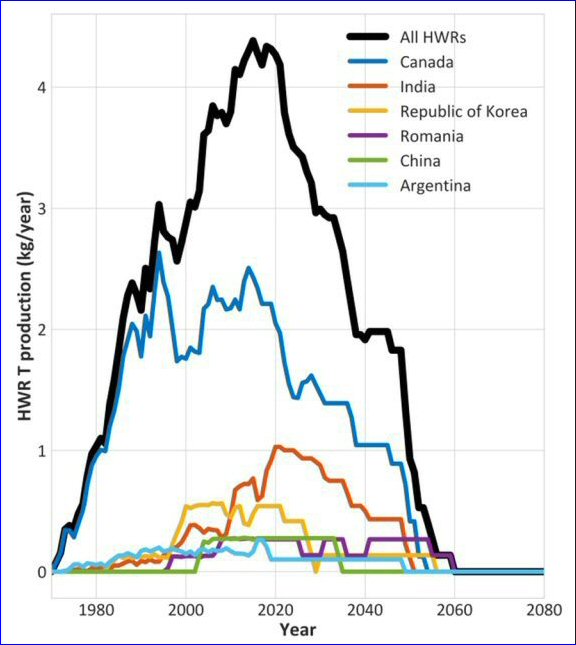

The world’s commercial tritium is produced from a small fleet of aging heavy-water nuclear fission reactors. Most are in Canada. After 2060, those reactors will have reached the end of their lifecycle, and Canada does not plan to replace them. The only proven way to produce more tritium is to build more heavy-water fission reactors.

After ITER, most of the seven partners on the international project will pursue their separate research efforts and build their own DEMO reactors. Tony Donné is the program manager for EUROfusion, the organization responsible for designing the EU DEMO reactor. If ITER is ever completed and if it ever performs the deuterium-tritium experiments for which it was designed, there would be no tritium left for any DEMO reactor.

In January 2022, I discussed the lithium issues with Donné and asked him about his planned source for the tons of enriched lithium needed for the EU DEMO reactor. He had none. He confirmed that the enrichment technology does not exist. He hoped that a solution will appear in the next few decades.

“We have enough time until the fusion reactors are rolled out to develop the technology and set up plants to enrich the lithium,” Donné wrote.

But the enriched lithium, if a method is developed to produce it, will be useless without tritium to start a deuterium-tritium fusion reactor.

In January 2022, Holland delivered a presentation to President Biden’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST). I requested and was granted an opportunity to respond during the meeting. I explained to the president’s science advisor and other members of the Council that the required fuel for fusion does not exist.

After the meeting, Holland submitted a written comment to the Council in response to my presentation. He did not refute a single technical point I had made. Instead, with no supportive evidence, he wrote, “The U.S. will have stable, reliable fuel sources for fusion energy.”

Worldwide tritium production as of 2017. Source: Kovari, M. Coleman, I. Cristescu, and R. Smith, “Tritium Resources Available for Fusion Reactors,” (Dec. 21, 2017) Nuclear Fusion, 58 (2)

On Oct. 15, 2020, the ITER organization secured an agreement with the government of Canada for the transfer of Canada’s tritium. Has Canada made any agreements to sell tritium to private companies in other countries? Has Argentina? India?

If not and if a method to enrich lithium at the scale needed for nuclear reactors does not exist, then can all the commercial deuterium-tritium fusion reactor claims coming from private companies be anything but a chimera, a delusion, or the world’s biggest technology scam?

| © 2026 newenergytimes.net |