By Steven B. Krivit

Dec. 15, 2022

In my reporting about the United States government announcement of a nuclear fusion research result at the National Ignition Facility, I was wrong about something.

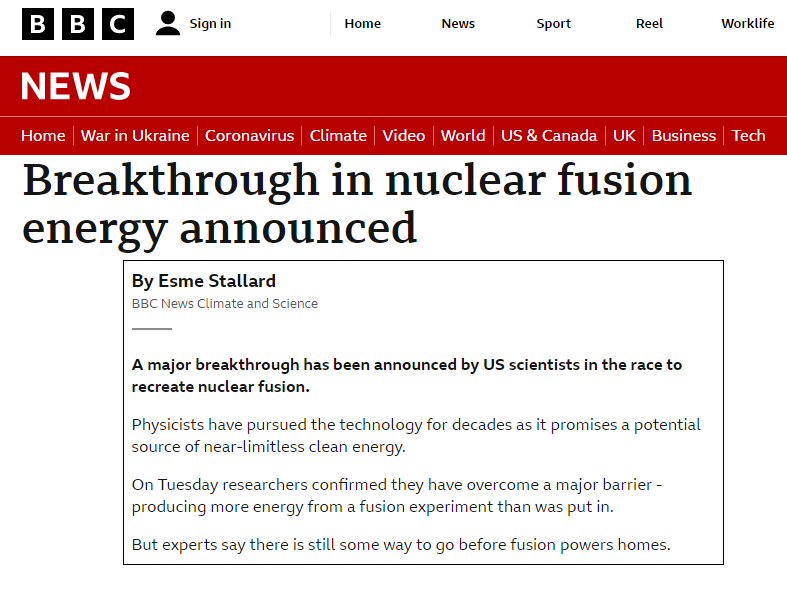

I first heard about the developing story on Sunday night when I began receiving text messages about it from friends. Tom Wilson of the London Financial Times had broken the story. I went online and realized that the news contained a major omission.

“Net energy gain indicates technology could provide an abundant zero-carbon alternative to fossil fuels,” Wilson wrote. His article explained that, from a 2.1 megajoule energy input, the experiment produced a 2.5 megajoule energy output.

I knew, as a specialist in nuclear energy research, that those values apply to only the energy going into and coming out of the fuel, and not the large amount of energy required to operate the NIF device.

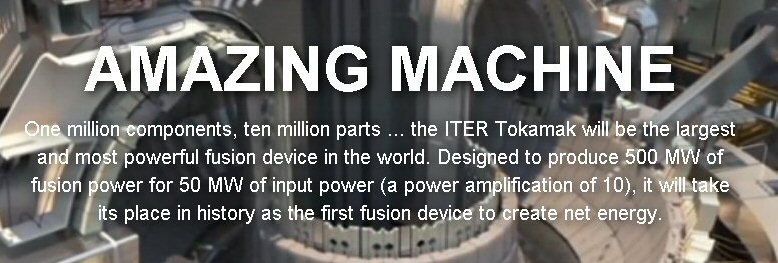

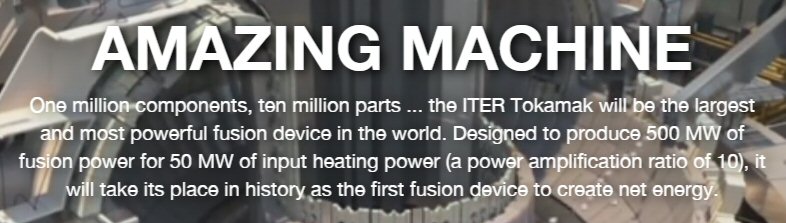

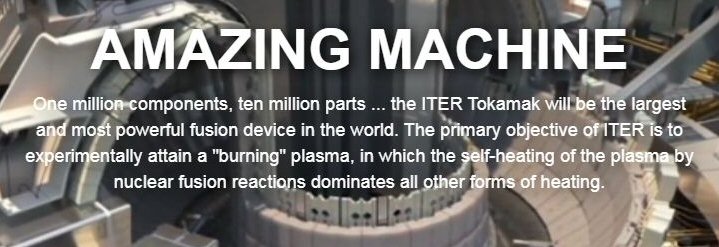

The promoters of the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), a magnetic fusion experiment, had been creating the same type of misunderstanding about the prospects of ITER, which I described in news stories five years ago.

A Question of Context

A year ago, my sources at the NIF lab had told me that the lasers consume 400 MJ of energy each time they run an experiment. Wilson had omitted this fact.

In the context of the actual NIF science accomplishment, the 400 MJ needed to operate the device is not relevant. But in the context of how the story was pitched — “abundant zero-carbon alternative to fossil fuels” — the net energy of the entire system was entirely relevant.

David Abel from the Boston Globe contacted me Monday morning and asked me to explain the numbers. The way the NIF story was playing out, as Abel accurately quoted me, “creates the false appearance that the device has produced net energy.”

But Abel immediately followed that with a comment from Mike Campbell, a former director of the one of the world’s leading centers for fusion research, the University of Rochester’s Laboratory for Laser Energetics.

According to Campbell, my critique was “misleading” because it implied the NIF result was associated with a practical demonstration of the NIF result.

“The experiment was only meant to show that the plasma in the fusion reaction could generate more energy than it consumed,” Abel wrote.

Then Campbell did exactly what he said I had done.

Campbell, as Abel paraphrased, “compared the breakthrough at the national lab to what the Wright Brothers did in Kitty Hawk, N.C. ‘They showed that a heavier-than-air machine could get off the ground; they weren’t designing a 787,’ Campbell said. ‘They showed that air travel was possible, if you could power it.”

The Wright brothers did get their plane off the ground and travel several dozen yards. But the NIF device did not demonstrate the production of a single Watt of power. Rather, it lost 99.2 percent of the energy it consumed.

Among the comments I have received from my readers, one stands out to me as the most thoughtful:

I hang my head in shame over the behavior over the last few days of my fellow scientists. It is being interpreted as the breakthrough that means commercial fusion is just days away. And the people being interviewed, who sometimes start with an honest description of what was achieved, are quickly losing their honesty and allowing the interviewer to misinterpret what they said.

I wasn’t wrong about the energy values. But I had thought that most of the news media who had reported the NIF result were to blame for the hype and exaggeration. That’s where I was wrong.

The Source

Yesterday, I saw what Kim Budil, the director of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), told the Wall Street Journal.

“This is one igniting capsule, one time. And to realize commercial fusion energy, you have to do many things,” Budil said.

The journalists, Jennifer Hiller and William Boston, made a reasonable, though optimistic interpretation from that. “[Budil] said it could take decades to commercialize fusion but that the achievement was a necessary first step that proves fusion could provide energy to a power plant.”

The NIF experiment lasted for 0.00000000009 of a second. The device produced no net energy. The device lost 99.2 percent of the energy it consumed. Suggesting to journalists who cannot be expected to be experts in nuclear fusion that this result “proves fusion could provide energy to a power plant” is beyond irresponsible. It is reprehensible.

Was Budil’s comment to the Journal a misquote? An isolated misstatement? Neither.

The news release from LLNL on Dec. 14 is rife with implications of laser fusion as a potential energy source. Here’s an example:

“I think it’s moving into the foreground and, probably with concerted effort and investment, a few decades of research on the underlying technologies could put us in a position to build a power plant,” Budil said.

The same news release explained that “with members of Congress, dignitaries and national laboratory directors in attendance, speakers at the stunning announcement celebrated the achievement as the culmination of 60 years of exploration and experimentation in ICF by generations of scientists.”

So after 60 years of laser fusion research, the last 10 using the most powerful laser fusion device in the world, laser fusion has demonstrated that it can produce slightly less than one percent of the energy it consumes.

A few journalists who reported this story have some training in physics. They knew better. But most journalists do not have training in physics. They are not to blame. They reported exactly what the officials told them. They omitted exactly what the officials — at least in the Dec. 14 news release — omitted; the device power consumption.

As a separate but equally important concern, the LLNL propaganda perpetuates the false claim about “limitless” energy from fusion. Even if NIF were to somehow miraculously produce net positive energy across the entire device, and repeat the 90-picosecond shots one after another, there is no tritium available in nature to fuel commercial reactors.

Any person who attempts to sell fusion to the public as a “limitless source of energy” without solving the multiple fuel issues is selling snake oil. Even the ITER organization, to its credit, withdrew its “unlimited energy” claim after I revealed that fallacy.

I am appalled, but sadly, not surprised at the behavior of the LLNL representatives. Taxpayers, rather than jubilant, should be outraged; not just for the falsehoods they have been told, but for the false hope these scientists have engendered and the diversion of our attention from other, more honestly promoted research.