Return to ITER Power Facts Main Page

December 7, 2020

Luo Delong, Chair of the ITER Council

Huang Wei, Vice-Minister of Ministry of Science and Technology, (China)

Massimo Garribba, Deputy Director-General, DG Energy, European Commission (European Union)

Ravi Bhushan Grover, Member, Atomic Energy Commission (India)

Matsuo Hiroki, Senior Deputy Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (Japan)

Chang-Yune Lee, Director General, Space and Nuclear Energy Bureau, Ministry of Science and ICT (Korea)

Igor Borovkov, Deputy Chief of Staff of the Government Executive Office of the Russian Federation (Russia)

Steve Binkley, Principal Deputy Director of the Office of Science, Department of Energy (U.S.)

Open Letter To the Chair and Heads of Delegation of the ITER Council:

Your organization is taking billions of taxpayer dollars in exchange for promises to the public that you know the ITER reactor will never deliver. You can’t change the reactor’s design but you can correct your claims. I encourage you to do so.

June 16, 2020, Letter

On June 16, 2020, in advance of the 26th ITER Council meeting, I wrote to some of you and explained the systemic pattern of false and misleading fusion claims that have surrounded the ITER project, including some of the activities of Director-General Bernard Bigot and the Head of Communications, Laban Coblentz.

After the 26th ITER Council meeting, I saw no improvement in the accuracy of the ITER organization’s public claims. Instead, a month after ITER Council 26, Bigot and Coblentz published a press release about ITER that contained a fraudulent claim about the primary measurable objective of the ITER project.

Nov. 15, 2020, Letter

On Nov. 15, 2020, I wrote to all the delegates of ITER Council 27. I brought the systemic patterns of false claims by Bigot and Coblentz to your attention. I provided you with samples of misleading claims on the ITER organization’s Web site. I provided you with samples of the many consequences of your organization’s false and misleading public claims.

In order to encourage positive change, I also provided you with a three-point outline of an accurate and transparent description of the primary measurable objective of the ITER project. I requested that the council inform me of its intentions by Nov. 23. Nobody from the council wrote back to me, let alone argued with any statement I made or facts that I presented.

At this point, every member of the council understands the problem. Every member of the council has an accurate and transparent description of the project available to use, if the council intends to honestly, accurately, and transparently describe the ITER project to the public.

Today, I’m going one step further, providing you with a condensed version of an accurate, transparent description of the ITER project.

Primary Measurable Objective

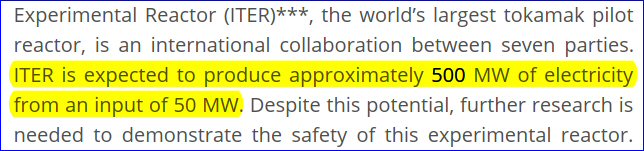

The primary measurable objective of the ITER reactor is the production of fusion reactions that have a thermal output of 500 megawatts. The input requires 50 megawatts of heat to be injected continuously into the reaction chamber. ITER is not designed for net power for the overall reactor; therefore, the 50-megawatt value does not include the power required to operate the reactor.

Let me remind you that, when communicating with the public, using the phrase “fusion power” when you actually mean “fusion reaction power” is dishonest. Everybody but plasma physicists thinks that fusion power is a form of power generation that would generate electricity. They think that claimed fusion power values represent usable, net rates of power (thermal or electric) that would be produced by fusion reactors. Nobody but plasma physicists understands that your use of the phrase fusion power applies only to the physics of the fusion reaction and that it fails to account for power required to operate a fusion device. Therefore, telling the public that ITER, which is equivalent to a zero-net-power reactor, is designed to produce “500 MW of fusion power” is dishonest.

In the words of Johannes Schwemmer, advice which he himself did not follow, the accurate way to represent the primary objective and goal of ITER is to “ensure that there is no possible misunderstanding on the ITER energy gain of 10- [that it is] linked only to the plasma and not to the energy balance of the overall ITER plant.”

In the words of European Commissioner Arias Cañete, who was apparently misinformed by the ITER management, “the IO Web site now states unambivalently that the performance of ITER will be assessed by the so-called fusion Q, i.e., by comparing the thermal power output of the plasma with the thermal power input into the plasma.”

Your collaborator Masahiko Inoue, on behalf of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, published an advertisement earlier this year demonstrating a perfect example of many of the false and misleading claims.

Excerpt from Mitsubishi Heavy Industries advertisement on Forbes Web site, July 13, 2020

You now have a concise, accurate, honest, and transparent three-sentence summary that describes the primary measurable objective of the ITER project. If the council intends to move forward with improved communications, please let me know by Dec. 18.

If you do not intend to communicate to the public accurately, honestly, and transparently, what conclusion can be drawn other than the entire upper management of the ITER organization is corrupt?

Sincerely,

Steven B. Krivit

Publisher and Senior Editor, New Energy Times

DISTRIBUTION

European Parliament

David Maria Sassoli, President

European Commission

Ursula von der Leyen, President

CHAIR OF THE ITER COUNCIL

Luo Delong

ITER COUNCIL — CHINA

Representatives

Huang Wei, Head of Delegation, Vice-Minister of Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST)

Chen Linhao, Deputy Director-General, Department of International Cooperation, Ministry of Science and Technology, MOST

Wang Min, Deputy Director-General, ITER CN DA

Experts

Zhou Wenneng, Deputy Director-General, MOST

LI Xinshuo, Third Secretary, Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Li Chunjing, Director, MOST

Yang Xuemei, Director, MOST

He Kaihui, Director, ITER CN DA, MOST

Liu Lili, Deputy Director, ITER CN DA, MOST

You Jiayu, Project Officer, MOST

Chen Yingqiao, Project Officer, ITER CN DA, MOST

ITER COUNCIL — EURATOM

Representatives

Massimo Garribba, Head of Delegation, Deputy Director-General, DG Energy, European Commission

Beatrix Vierkorn-Rudolph, Chair of the Governing Board, F4E/Euratom Domestic Agency

François Jacq, High Representative for ITER in France and CEA Chairman

Experts

Johannes Schwemmer, Director, F4E/Euratom Domestic Agency

Jean-Marc Filhol, Head of the ITER Program Department, F4E/Euratom Domestic-Agency

Eric Kraus, Director, Agence ITER France

Carles Dedeu, Deputy Head of Unit, DG ENER, European Commission

Alice Whittaker, Policy Officer, DG ENER, European Commission

Benoît Fourestié, Project Officer, DG ENER, European Commission

Alessia Bizzarri, Policy Officer, DG ENER, European Commission

Michel Claessens, Policy Officer, DG ENER, European Commission

Johannes De Haas, Programme Officer, DG ENER, European Commission

ITER COUNCIL — INDIA

Representatives

Ravi Bhushan Grover, Head of Delegation, Member, Atomic Energy Commission

Shashank Chaturvedi, Director, Institute for Plasma Research

Ranajit Kumar, Head, Nuclear Controls & Planning Wing, Department of Atomic Energy

Sushma Taishete, Joint Secretary (R&D), Department of Atomic Energy

Experts

Ujjwal Baruah, Project Director, ITER-India

Shishir P. Deshpande, Sr. Professor, Institute of Plasma Research

Arun K. Chakraborty, Associate Project, ITER-India

Mahaboob Basha Syed, Member, Nuclear Control and Planning Wing, Department of Atomic Energy

ITER COUNCIL — JAPAN

Representatives

Matsuo Hiroki, Head of Delegation, Senior Deputy Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT)

Uezono Hideki, Director, International Science Cooperation Division, Disarmament, Non-proliferation and Science Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Iwabuchi Hideki, Director, International Nuclear and Fusion Energy Affairs Division, Research and Development Bureau, MEXT

Kamada Yutaka, Advisor to the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and Deputy Director General, Naka Fusion Institute, Fusion Energy Directorate, National Institute for Quantum and Radiological Science and Technology

Experts

Takeiri Yasuhiko, Director-General, National Institute for Fusion Science, National Institutes of Natural Sciences

Furuya Kaori, Chief, ITER Unit, International Nuclear and Fusion Energy Affairs Division, Research and Development Bureau, MEXT

Seki Yohji, Administrative Researcher, International Nuclear and Fusion Energy Affairs Division, Research and Development Bureau, MEXT

Tsuji Shino, Deputy Director, International Science Cooperation Division, Disarmament, Non-proliferation and Science Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Kurihara Kenichi, Managing Director, Fusion Energy Directorate, National Institute for Quantum and Radiological Science and Technology (QST)

Sugimoto Makoto, Director, Department of ITER Project, Naka Fusion Institute, Fusion Energy Directorate, QST (Head of JADA)

Matsumoto Taro, Deputy Director, Department of Research Planning and Promotion, Fusion Energy Directorate, QST

Taniguchi Masaki, Group Leader, ITER and BA Promotion Group, Fusion Energy Directorate, QST

HAMAGUCHI Dai, Principal Researcher, ITER and BA Promotion Group, Fusion Energy Directorate, QST

ITER COUNCIL — KOREA

Representatives

Chang-Yune Lee, Head of Delegation, Director General, Space and Nuclear Energy Bureau, Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT)

Kiseok Kim, Director, Nuclear and Fusion Energy Cooperation Division, MSIT

Dongmin Hwang, Deputy Director, Nuclear and Big Science Cooperation Division, MSIT

Suk Jae Yoo, President, National Fusion Research Institute (NFRI)

Experts

Hyeon Gon Lee, Vice-President, NFRI

Ki Jung Jung, Director-General of ITER Korea, NFRI

Seung-Min Shin, Head of External Relations Team, ITER Korea, NFRI

ITER COUNCIL — RUSSIAN FEDERATION

Representatives

Igor Borovkov, Head of Delegation, Deputy Chief of Staff of the Government Executive Office of the Russian Federation

Viacheslav Pershukov, Special representative of the Atomic Energy Corporation ROSATOM on International and Science and Technology Projects

Viktor Ilgisonis, Director of the R&D programs of the Atomic Energy Corporation ROSATOM

Sergey Mazurenko, Member of the RF Presidential Council for Science and Education

Experts

Anatoly Krasilnikov, Head, RF ITER Domestic Agency

Vitaly Korzhavin, Deputy Head, RF ITER Domestic Agency

Vladimir Vlasenkov, Deputy Head, RF ITER Domestic Agency

ITER COUNCIL — U.S.A

Representatives

Steve Binkley, Head of Delegation, Principal Deputy Director of the Office of Science, Department of Energy (DOE)

James W. Van Dam, Associate Director, Office of Fusion Energy Sciences, Office of Science, DOE

Jonathan Margolis, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Science, Space and Health, Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs, Department of State (DOS)

Joseph May, Director, Facilities, Operations and Projects Division, Office of Fusion Energy Sciences, Office of Science, DOE

Experts

Harriet Kung, Deputy Director for Science Programs in the Office of Science, DOE

Thomas J. Vanek, Senior Policy Advisor, Facilities, Operations, and Projects Division, Office of Fusion Energy Sciences, Office of Science, DOE

Jeff Thomas, Senior Policy Advisor in the Office of Fusion Energy Sciences, DOE

Cole Donovan, Foreign Affairs Officer, Office of Science and Technology Cooperation, Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs, DOS

Esha Mathew, Foreign Affairs Officer, Office of Science and Technology Cooperation, Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs, DOS

Gabriel Swiney, Legal Advisor, DOS

Kathy Mccarthy, Project Director, US ITER

ITER COUNCIL — CHAIR OF THE FINANCIAL AUDIT BOARD

Alexander Zagornov

ITER COUNCIL — CHAIR OF THE MANAGEMENT ADVISORY COMMITTEE

Shirai Hiroshi

ITER COUNCIL — CHAIR OF THE SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY ADVISORY COMMITTEE

Yong-Seok Hwang

IAEA

Mikhail Chudakov, Deputy Director General, Head of the Department of Nuclear Energy

Melissa Denecke, Director of the Division of Physical and Chemical Sciences, Department of Nuclear Sciences and Applications