Note from Steven B. Krivit: I want to thank my colleague Celia Izoard for doing what I have been unable to do so far: boots-on-the-ground reporting directly from the ITER construction site. Her other two thoughtful articles go into important details that I have not covered and I encourage readers to have a look at them as well.

Researched and Written by Celia Izoard

Originally published in French by Reporterre June 16, 2021

English Version by Steven B. Krivit, Oct. 9, 2021

Overview of the ITER Site, in November 2020 — Photo: ITER organization / EJF Riche

Part 1: The Future ITER Nuclear Reactor: A Titanic and Energy-Intensive Project

ITER, in Bouches-du-Rhône, will consume as much energy as it produces. This huge project is also much more expensive than expected: 44 billion euros.

The reality behind the promises of nuclear fusion: ITER, the future international reactor, intends to be the showcase of nuclear fusion, whose qualities, according to its promoters, surpass those of fission, as used in conventional power stations. We investigate the heart of a disproportionate project which has potentially disastrous health and environmental consequences.

Parts 2 and 3 (French only) Available at Reporterre

Part 2: Behind the ITER Project, Mountains of Toxic Metals and Radioactive Waste

Part 3: The ITER Chasm Does Not Discourage Thermonuclear Fusion Projects

Reporting from Saint-Paul-lez-Durance (Bouches-du-Rhône)

In Cadarache, in the Bouches-du-Rhône, several thousand people are working on one of the largest construction sites in the world. The complex where we enter with our guide, which will house the future ITER Nuclear Fusion Reactor (International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor,) weighs 440,000 tons, or more than forty Eiffel Towers.

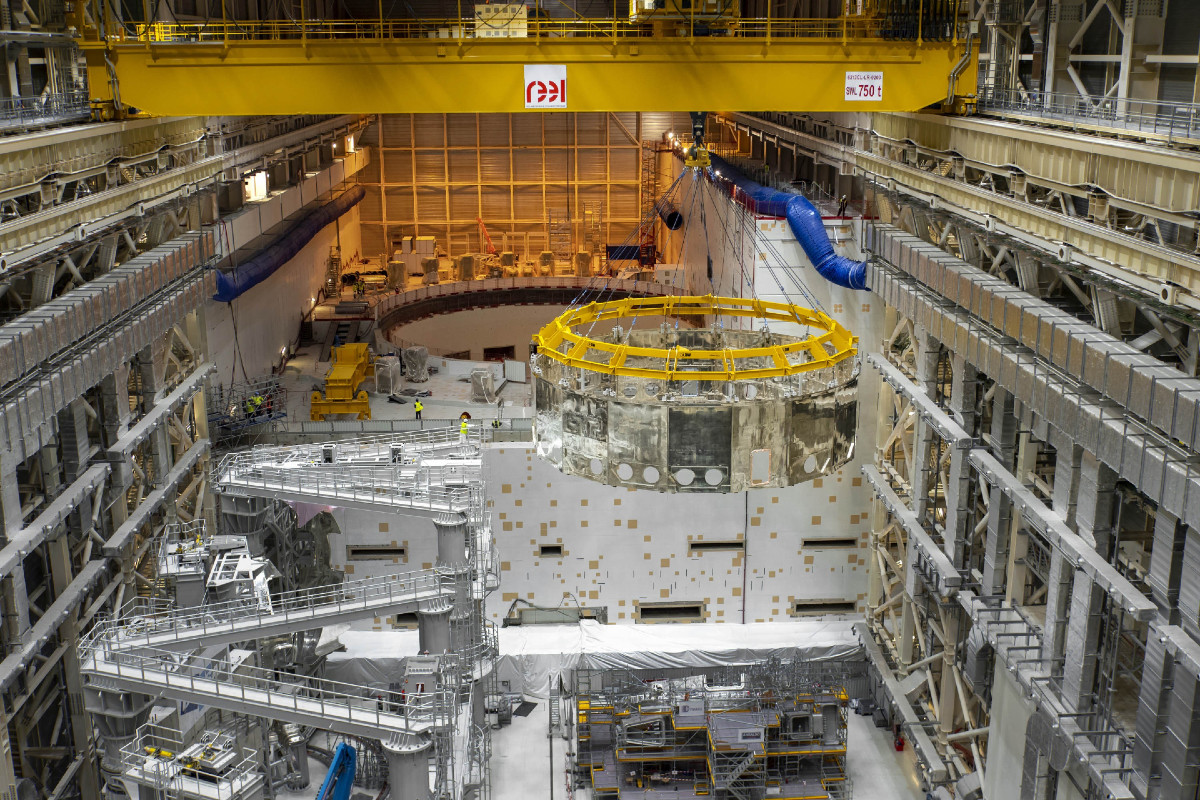

Men and women in construction helmets –“red helmets for the bosses, white for the workers,” explains the guide — all equally dwarfed in this immense space, contemplate a colossal piece of metal weighing 440 tons. It was shipped from China by boat, transported from Fos-sur-Mer on a barge specially built on the Etang de Berre, then transported by night convoy on 104 kilometers of fortified road aboard a giant truck equipped with 352 wheels.

If members of an unknown tribe arrived at the ITER site and observed the titanic resources mobilized for this project, they would probably conclude that a temple is being built here for the worship of a god. They might not be wrong. The name of this deity appears in large letters on the first page of the ITER organization’s Web site: “UNLIMITED ENERGY.”

French home page of the ITER organization. Screenshot:ITER.org

Nuclear power plants built from the 1960s had already promised to answer this prayer, but by means of fission: triggering a chain reaction releasing neutrons by breaking apart uranium nuclei. But with ITER, its proponents say bluntly: nuclear fission is a dead end. Uranium must be extracted to fuel reactors. Fission requires the management of tens of thousands of tons of radioactive waste for thousands of years. Fission chain reactions must be carefully controlled and, if not properly cooled, become uncontrolled, as in Fukushima.

“We no longer want all that,” says Joëlle Elbez-Uzan, the director of safety and environment at the ITER organization.

With nuclear fusion, its proponents assure us, all these problems go away: it needs very little fuel, generates very little waste, and has no risk of runaway reactions. With deuterium (extracted from sea water) and only a few kilograms of radioactive tritium, heated to between 150 and 200 million degrees Celsius (ten times the temperature of the center of the sun), they say, we can create a plasma from fusion and produce enormous levels of heat. [1]

“Fusion can generate four times more energy per kilogram of fuel than fission, and nearly four million times more energy than burning oil or coal,” promises the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) on the front page of its bulletin published in May 2021.

One of the Sections of the ITER tokamak vacuum chamber – ITER organization

Tenfold Increase in Power. Really?

So far, this information is nothing new: Fusion is the principle behind the thermonuclear bomb (or H-bomb). As physicists explained in 1957, shortly after the international “Atoms for Peace” conference, which initiated fusion research, the purpose of a thermonuclear fusion reactor is to “harness the energy of the H-bomb.” [2]

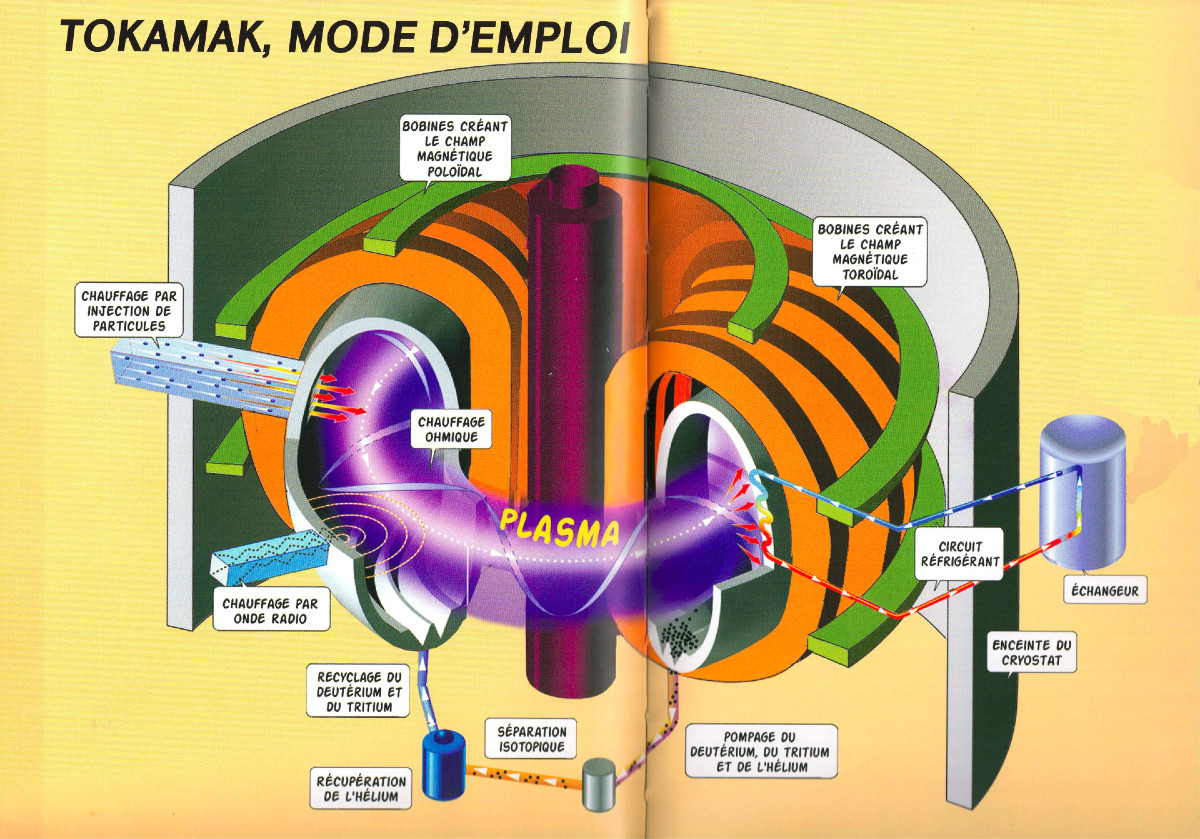

Instead of giving free rein to the destructive energy of the neutrons, fusion scientists will try to confine plasma in gigantic magnetic fields. Locked in this tokamak, a sort of magnetic bottle invented by Russian physicists, the plasma, raised to very high temperature, would produce helium nuclei, and the fusion reaction, scientists imagine, would be self-sustaining. We could then, fusion scientists say, recover the excess heat created by the reaction and convert it into electric current.

Diagram of the tokamak reactor, showing the vacuum chamber as the gray cylinder, surrounding the coils that generate the magnetic field. Source: CEA, “ITER: the path to the stars?”, J. Jacquinot, R. Arnoux, Edisud, 2006.

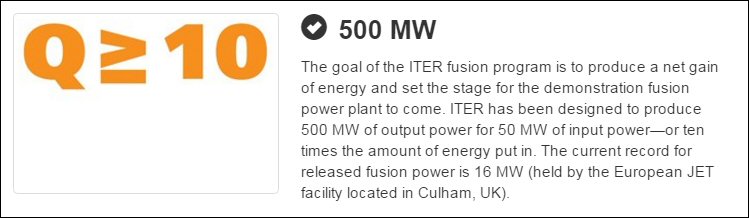

Until now, nuclear fusion could only be carried out for a few seconds — they claim — due to the lack of a tokamak large enough to contain the energy. [3] [N1]

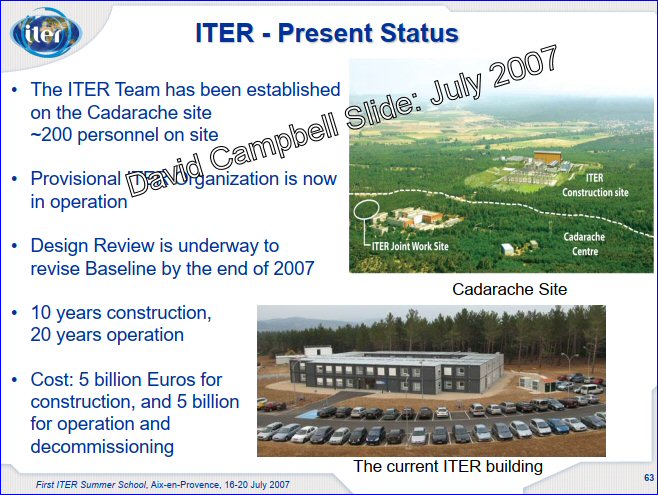

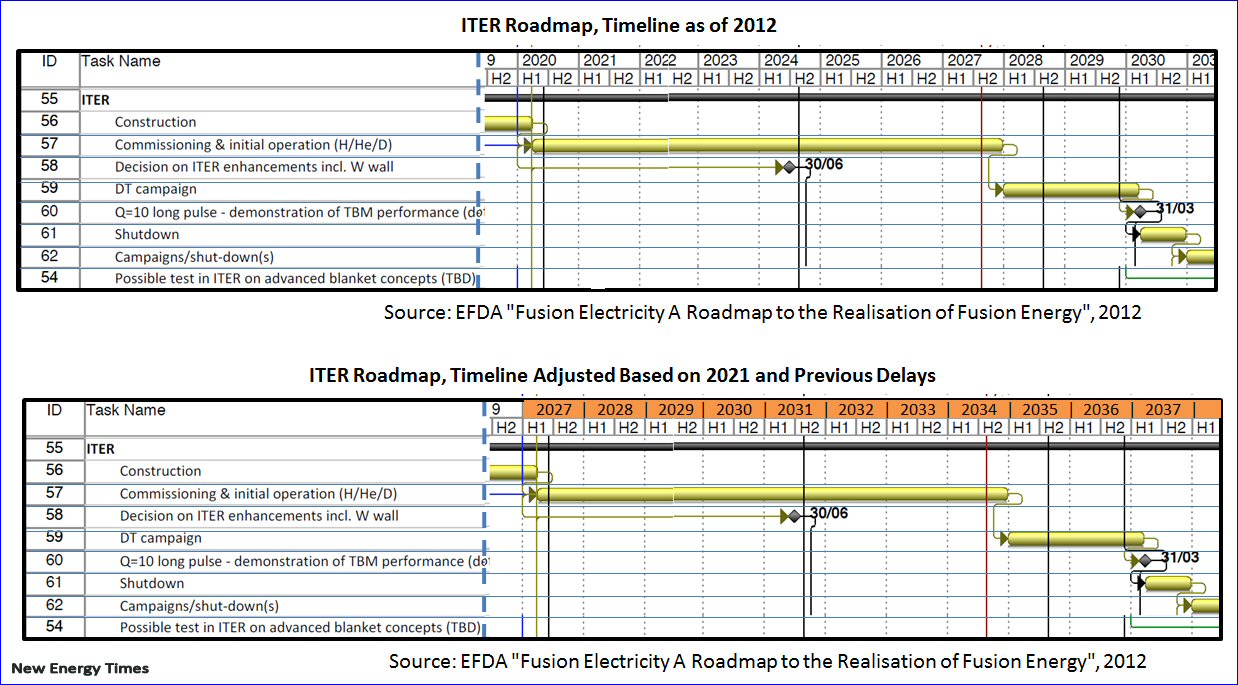

Because no country could have assumed alone the costs of such a construction, the experiment conducted at Cadarache brings together thirty-three countries (European Union, United States, China, Russia, Japan, India and South Korea), who all contribute to its financing. [N2] After 15 years of work and research, the assembly of the ITER tokamak – a gigantic metal enclosure 73 meters high – began in the summer of 2020. The objective is to succeed in confining a fusion plasma for four minutes.

Because of its experimental purpose, ITER will not be connected to turbo-alternators and will not produce electricity. The first firing of plasma with deuterium and tritium will not begin until 2035, according to the current schedule, after the machine has been assembled, and its stability and tightness tested. A European prototype reactor, the EU DEMO, would be built around 2050, according to the ITER organization, then a whole nuclear fusion utility sector “by 2070,” estimates Joëlle Elbez-Uzan cautiously.

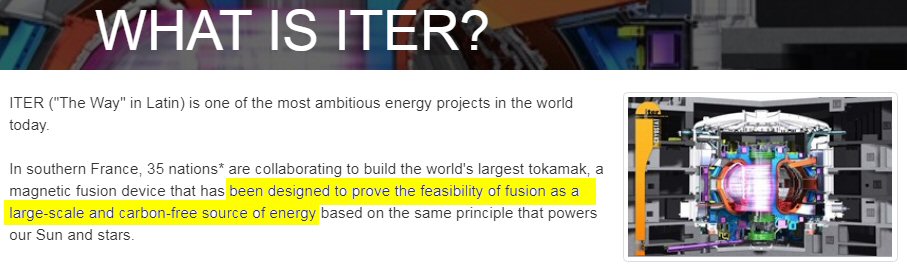

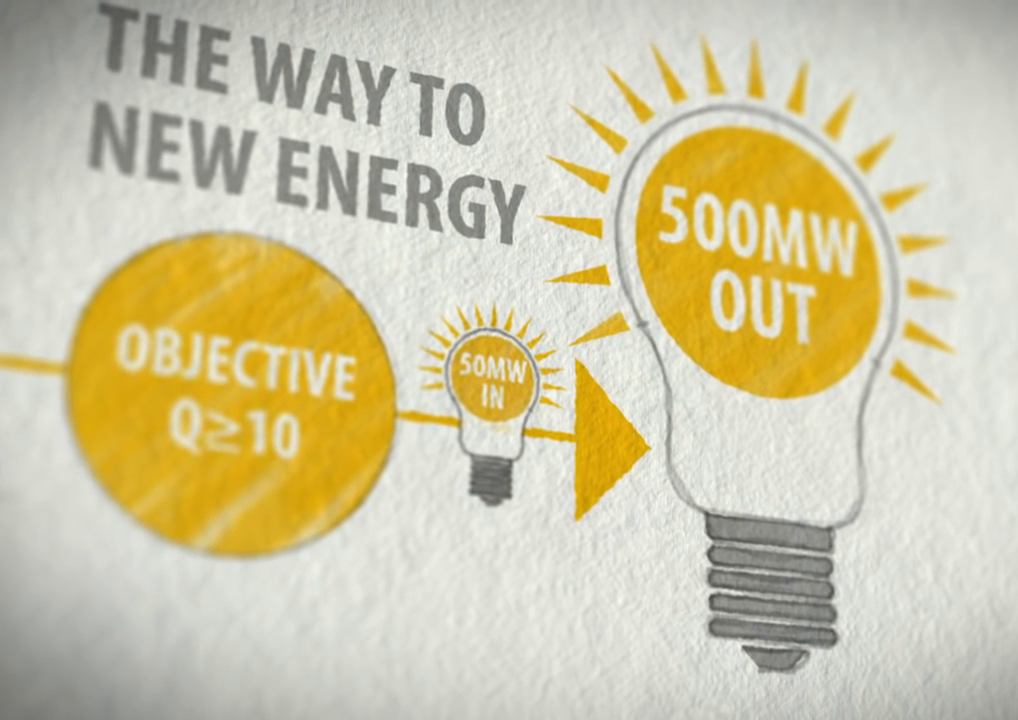

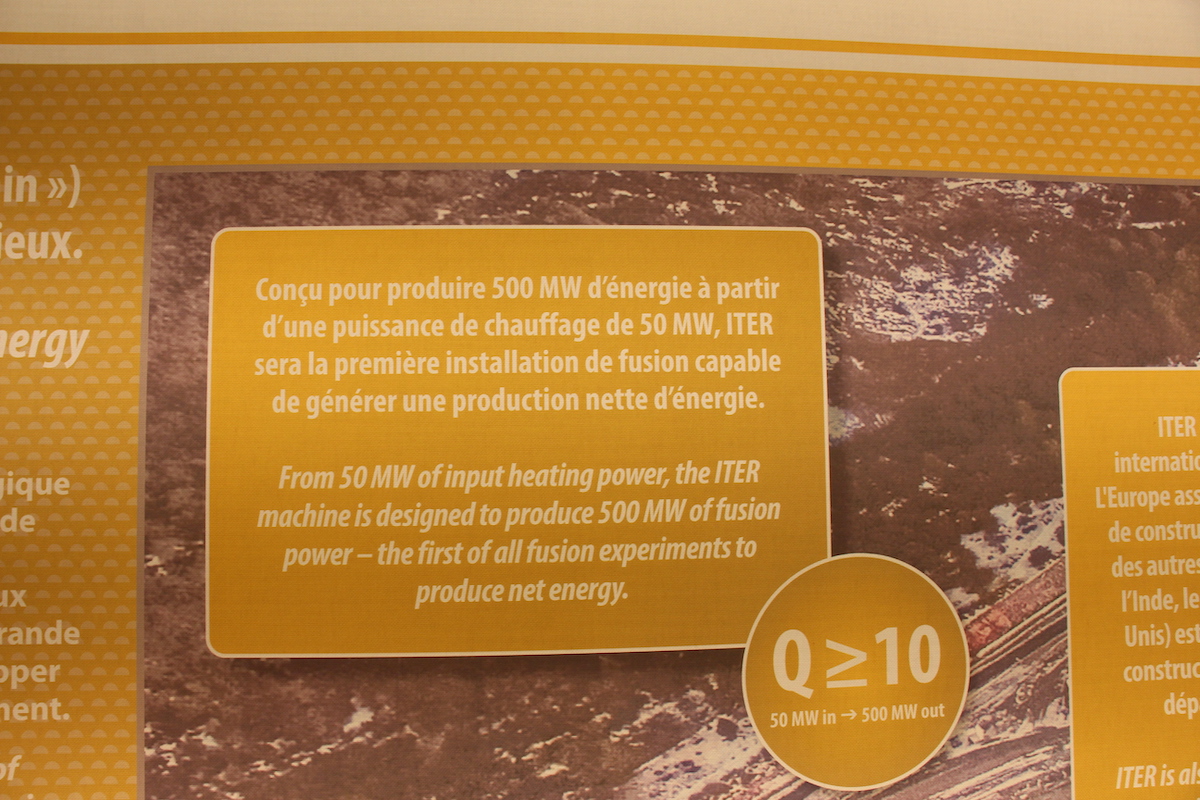

But ITER already intends to demonstrate that the reactor will generate “the first net energy production in the history of fusion” by creating an “amplification by a factor of 10: i.e. 50 megawatts (MW) input and 500 megawatts output.” This is the first thing the ITER organization claims: With very little fuel and waste, we will increase the power tenfold: we will inject 50 MW, and we will obtain 500 MW.

In Cadarache, information panel on ITER. © Celia Izoard / Reporterre

Zero Power Balance

The problem is, it is wrong. Or, at least, this is only very partially true. Steven B. Krivit, American scientific journalist, specialist in nuclear fusion, devoted an investigation to it, then a film. At the time of the plasma firing, he explains, to produce the 50 MW of heat that will be injected into the tokamak, and taking into account all the systems required for the reactor, the heating systems and the energy losses, ITER will consume between 300 and 500 MW of high-grade electrical power. That’s almost as much as the low-grade thermal power it is supposed to produce. That doesn’t count the grey energy needed for the mining extraction, the electronics production, the chemicals, and the transportation of all these parts upstream.

“This reactor is designed to produce fusion particles – neutrons and helium – which have ten times the rate of power injected into the fuel to create these particles,” explains Steven B. Krivit, “and not to produce ten times the rate of power consumed by the overall reactor.”

If the experiment conducted at ITER works, and it is connected to the grid, the power balance would be zero. A “strategic omission,” according to Krivit, which considerably removes any prospect of producing electricity by nuclear fusion.

Inside the ITER site. © Celia Izoard / Reporterre

This subtle distinction between the rate of power injected into and used to heat the fuel and the rate of power consumed by the reactor (like its giant cryogenic plant) is never explained to the public or even, presumably, to ITER’s staff. When we corrected Joëlle Elbez-Uzan during our interview on the fact that the amplification factor by ten only concerns the reaction, and not the total power rate consumed by ITER, the safety director exclaimed, perplexed: “Are you playing a joke on me?”

Asked the same day about ITER’s total power consumption, Laban Coblentz, communications director, replied that he did not know. After a written request, plus fifteen days of waiting and several reminders, Coblentz provided approximate numerical values confirming those of Steven B. Krivit, but he accompanied them by a long dissertation on the need to “place these answers in the context of the mission of ITER.”

Its energy consumption, he said, must be weighed against “the enormous potential of fusion to eliminate more than a century of geopolitical tensions and conflicts linked to access to fossil resources.”

Part of the power consumed by ITER, according to Coblentz, is “the large number of diagnostic tools aimed at an exhaustive analysis of the plasma and used to optimize the design of future machines.” And anyway, he says, it is impossible to precisely estimate the power consumption because “it will depend on the precise configuration of the systems used for each experiment.”

This admission of ignorance by Coblentz is all the more surprising because at the time of the public debate on ITER in 2006, the project’s managment seemed perfectly capable of providing an estimate. The report of the meeting organized in Salon-de-Provence by the National Commission for Public Debate indicates: “When the machine is in standby mode, it will consume 120 megawatts in order to supply the auxiliaries. During the experiments, the power consumed […] will then reach 620 MW in order to heat the plasma, then drop to 450 MW during the main phase of the experiment (370 seconds), and will be restored to 120 MW. At peak power of 620 MW, compensation systems will limit ITER’s impact on the regional electricity grid. [4].”

And for good reason! 620 MW represents an enormous power drain, since the entire Toulouse metropolitan area uses power of nearly 500 MW. Year-round, we learn in one of the notebooks intended for public debate, ITER will consume 600 GWh [5], which corresponds to the supply of a city of 145,000 inhabitants, such as Aix-en-Provence or Le Mans.

The first element of the cryostat heat shield transferred to the tokamak pit on January 14, 2021 © ITER organization

From 4.5 Billion to 44 Billion Euros

Obviously, the officials of the ITER organization carefully avoid mentioning the cost, for fear of dampening the enthusiasm of the political leaders who finance this colossal instrumentation.

“A small group of physicists representing the nuclear fusion research community has misinformed the public in order to ensure the continuity of its public funding,” summarizes journalist Steven B. Krivit.

To convince the political leaders, it was necessary at least to promise an energy miracle worthy of the multiplication of the loaves. “This is the sledgehammer aargument,” Thiéry Pierre, a plasma physicist at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, told Reporterre. He is very skeptical about the possibility of confining a thermonuclear plasma. “Imagine scientists, crowned with the prestige of theoretical physics, explaining to Jacques Chirac that energy can be multiplied by ten: he writes the check right away!”

Today, the people involved in fusion have all the less interest in disappointing their interlocutors as the costs keep doubling. In 2000, ITER was supposed to cost 4.5 billion euros. In 2006, the year in which the ITER Agreement was ratified by Jacques Chirac, the total cost (construction, operation and decommissioning) was estimated at 10 billion euros. The ITER organization today says the cost is 22 billion Euros but Laban Coblentz admits “this excludes operating costs and decommissioning.”

Even more, it is all the more false to quantify the cost of the project at 22 billion euros since, according to the ITER Agreement, the European Union contributes to the project up to 45.6% of the total amount, yet the EU has allocated 20 billion euros until 2035. According to this agreement, the other six partner countries contribute the rest of the cost through in-kind contributions: the supply of all these unique very high-tech components, always from public funds. The construction cost would therefore be around, according to physicist Thiéry Pierre, “44 billion euros,” which led him to send a note to the management of the National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), asking to put an end to this disinformation “which risks casting permanent discredit on plasma physics.”

Finally, by adding the billions needed to run the experiments and deal with a massive volume of decommissioning waste, the U.S. Department of Energy may have been more realistic in estimating the total cost of ITER at 65 billion dollars (approximately 54 billion euros). Apart from the International Space Station, it is the most expensive scientific experiment in human history.

Reporterre Notes:

- The fusion that will take place in ITER is called “thermonuclear.” By heating, it accelerates deuterium and tritium nuclei so as to make them overcome electrostatic repulsion and to fuse them, which emits very energetic neutrons. Heating takes place in different stages. First, gaseous fuel is introduced into the tokamak and electricity passes through the large central magnet, which itself sends a current through the gas. This is ohmic heating, which works on the principle of resistance and which makes it possible to reach the temperature of 20 million degrees Celsius. Second, two complementary heating techniques are introduced to reach 150 million degrees: neutral particles are injected into the plasma, giving it energy and two sources of high frequency electromagnetic waves are activated.

- “Nuclear fusion: energy in abundance,” The scientific method, France Culture, June 12, 2019.

- For example, in the JETtokamak in England and the West tokamak at the CEA in Cadarache. And more recent announcements from Korea ( KSTAR ) and China (East).

- Report of the public debate on ITER in Provence, National Commission for Public Debate, 2006, p. 43.

- ITER en Provence, National Commission for Public Debate, Cahier 1, 2006, p. 23.

New Energy Times Notes:

N1. According to plasma physicist Daniel Jassby, a “tokamak large enough to contain the energy” as the limitation for the duration of experiments is nonsense. Jassby says that the primary limitation is because of the maximum duration of the toroidal current. With reactor designs that did not use superconducting coils, the secondary reason was because of potentially excessive heating of the magnetic field coils, which would have caused them to melt. A tertiary limitation is the challenge to remove, not contain, the heat produced in fusion reactors.

N2. Switzerland and England are no longer partner nations to the ITER project and the number of partner countries has been corrected in this version.