Return to the Fusion Fuel Main Page

By Steven B. Krivit

Oct. 10, 2021

The First of a Three-Part New Energy Times Investigative Science Report

Part 2: The Tritium Fusion Fuel Discrepancy: The Misleading Claims

Part 3: Serious Discrepancies with ITER and Nuclear Fusion

ABSTRACT

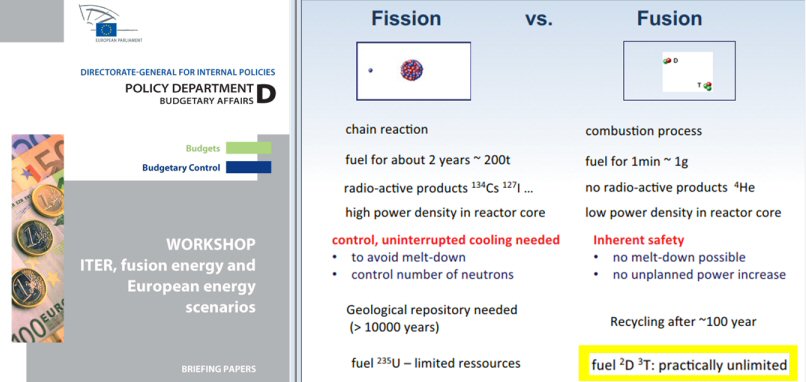

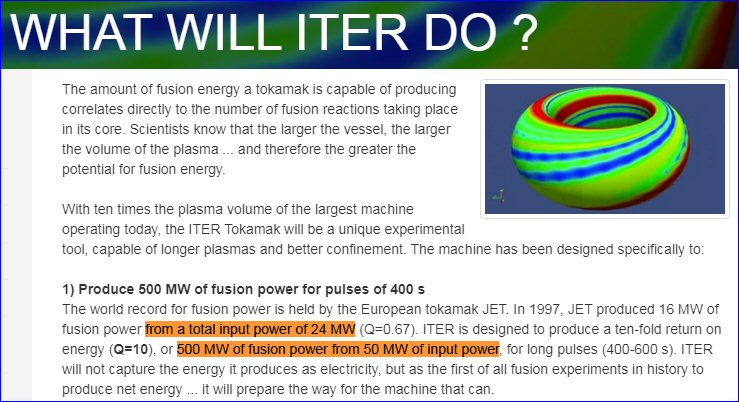

Significant discrepancies exist about the forthcoming ITER fusion reactor. These discrepancies could spell disaster for the ITER project as well as for future fusion reactors. Fusion promoters sold the idea of ITER to the public, news media, and elected officials primarily based on these two false claims:

FUEL SOURCE: They said the fuel for fusion was abundant, inexpensive, and universally available. Actually, one of the two required fuel components is. The other does not exist as a natural resource on Earth.

POWER GAIN: They said the ITER reactor (not just the physics reaction) was designed to produce 10 times the power it would consume. They said ITER would be the first fusion reactor (not just the physics reaction) to demonstrate net power production. Actually, if ITER works correctly, there will be no reactor power gain. The reactor will lose power.

FUSION INVESTIGATION

New Energy Times uncovered the input power requirement for the JET reactor, and thus the discrepancies with the JET and ITER reactors, on Dec. 1, 2014. We began reporting on the ITER power discrepancy on Dec. 14, 2016. We uncovered and published the input power value for ITER on Oct. 6, 2017. We began reporting on the fuel discrepancy on July 1, 2017, and published extensive reporting on the fuel discrepancy on Oct. 10, 2021.

Scientists who promoted nuclear fusion research to the public, news media, and elected officials have long claimed that the fuel needed for nuclear fusion reactors will be abundant, inexpensive, and virtually unlimited. Those claims are only half-true.

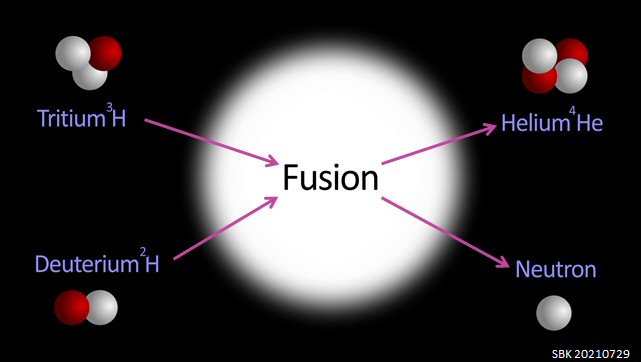

The main approaches to nuclear fusion require a mixture of two forms, or isotopes, of hydrogen: deuterium and tritium. The consensus among fusion scientists is that a 50-50 fuel mixture of the two isotopes will be required for commercial fusion reactors.

One of these isotopes (deuterium) can be separated from water in the ocean and can thus legitimately be described as abundant, inexpensive, and virtually unlimited.

The other hydrogen isotope — tritium — does not exist on Earth as a natural resource.

Here are some examples of the claims made by fusion scientists:

- “If the whole planet was run on fusion, there would be enough fuel in the ocean for two billion years.” (Michel Laberge)

- “Nobody owns the fusion fuel. The machines are expensive, but the fuel cost is essentially zero.” (Thomas Klinger)

- “Fuels are plentiful and available all over the world.” (Johannes P. Schwemmer)

- “The energy content stored in the ocean would last humanity for 100 million years.” (Mark Henderson)

- “It’s an inexhaustible, carbon-free source of energy that you can deploy anywhere and at any time.” (Dennis Whyte)

Lots of Deuterium

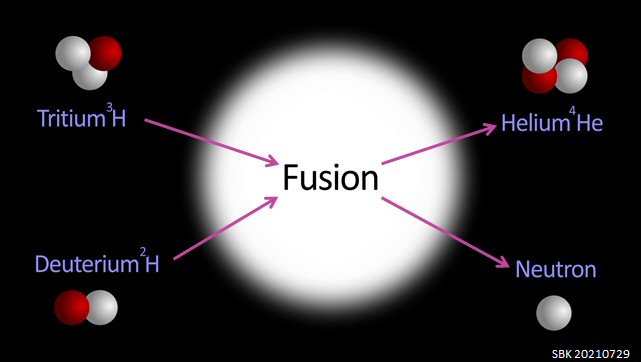

A normal hydrogen isotope contains only a positively charged proton in its nucleus, but the deuterium isotope adds a neutral particle: a neutron. The hydrogen isotope known as tritium has one proton and two neutrons in its nucleus. Both deuterium and tritium are required for the fuel mixture in fusion reactors.

When deuterium and tritium react and undergo nuclear fusion, a lot of energy is released. In the process, the tritium and deuterium are transmuted into a single, larger atom — helium — along with a leftover neutron.

Deuterium-tritium nuclear fusion reaction diagram

The deuterium-tritium fuel mix is necessary to produce energy levels and reaction rates that have any hope of producing practical levels of energy.

Is fusion possible with deuterium but not tritium? Yes; but achieving useful power levels from fusing pairs of deuterium under conditions available on Earth is considered impossible. Can a smaller fraction of tritium permit fusion reactors to produce useful levels of energy? No. Well-known scientific data show that a 50-50 mixture of tritium and deuterium is required to provide the necessary output level for useful power. Would a tritium-tritium reaction perform better? Actually, no. The deuterium-tritium fuel mix gives the highest energy yield.

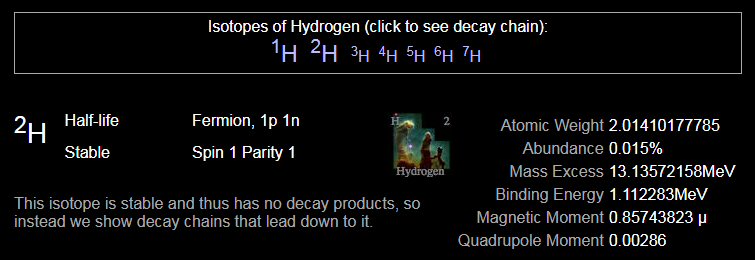

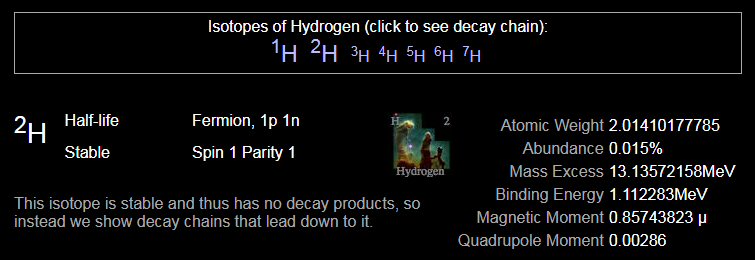

Among the seven known isotopes of hydrogen, normal hydrogen, designated with a superscript 1 followed by the letter H, comprises 99.985 percent of all forms of hydrogen on Earth. Deuterium, designated with a superscript 2 followed by the letter H, comprises the remaining 0.015 percent of hydrogen isotopes on Earth.

Natural abundance of deuterium on Earth. Courtesy www.periodictable.com

Even at an abundance of only 0.015 percent, ocean water has enough deuterium to qualify as a nearly unlimited resource. But tritium is another story.

Tritium Issue #1: It Doesn’t Exist as a Natural Resource

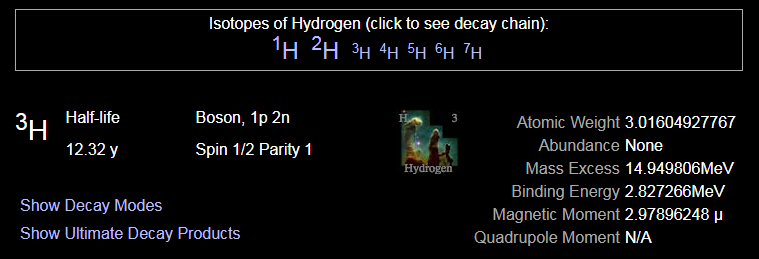

Tiny amounts of tritium are produced by nature in the upper atmosphere when cosmic rays strike nitrogen molecules. This tritium is incorporated into water and falls to Earth as rain. Of the three hydrogen isotopes, tritium comprises about a billionth of a billionth percent. Earth has so little tritium that its natural abundance is listed as “none.” Therefore, we can accurately say that tritium does not exist as a natural resource on Earth.

Natural abundance of tritium on Earth. Courtesy www.periodictable.com

The situation is not completely hopeless, however; there are ways to make tritium. The U.S. military had operated complex and costly reactors that could make tritium, but they have since been decommissioned, according to Daniel Jassby, a retired plasma physicist from the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, who is the author of two articles in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

That’s because tritium doesn’t last. It’s radioactive, and the moment fresh tritium is produced, it starts undergoing radioactive decay and begins changing into non-radioactive helium. After 12.3 years, half of the initial amount of tritium is gone. For this reason, significant amounts of tritium cannot be produced in advance and stockpiled.

The military always needs fresh tritium. Tritium is used as a component of nuclear weapons, and the helium-3 decay product must be periodically extracted and replaced with fresh tritium, at great expense.

“The military is now forced to generate tritium by implanting lithium control rods in two Tennessee Valley Administration fission power reactors,” Jassby wrote. “The U.S. military has no tritium to sell to anybody.”

Tritium is also made in nuclear fission reactors. It’s an unintended radioactive byproduct of fission reactions. Mohamed Abdou, a fusion and tritium expert at the University of California, Los Angeles, explained this in a 2020 meeting.

“Fission reactor operators do not really want to make tritium because of permeation and safety concerns. They want to minimize tritium production, if possible,” Abdou said. [1]

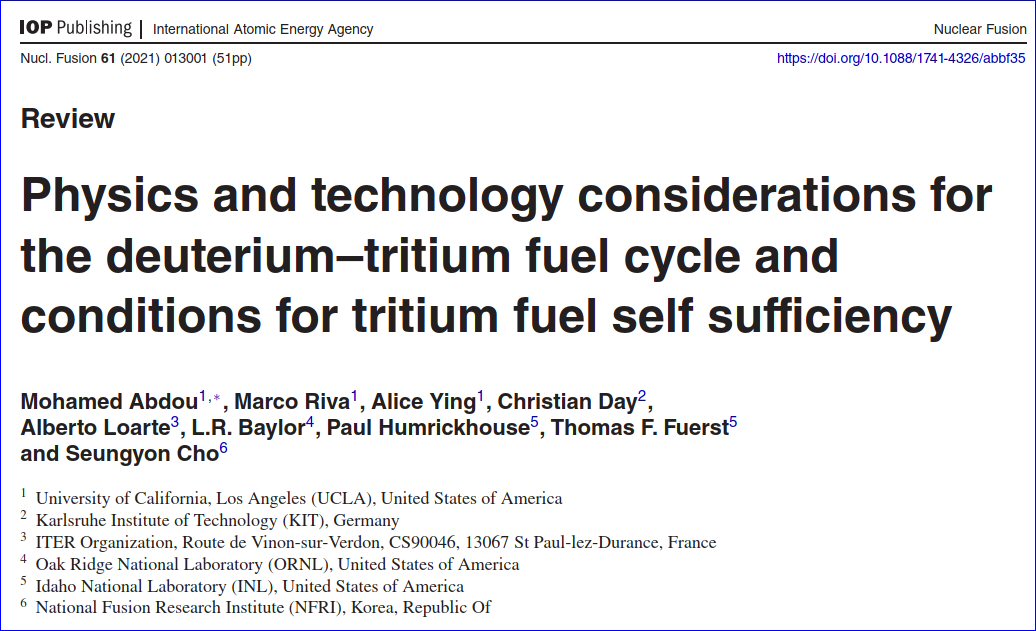

Abdou is the lead author of a key technical paper on tritium shortfalls for nuclear fusion. [5]

Tritium Issue #2: Production Is Scarce

But not all nuclear fission reactors produce tritium at useful rates. Most of the world’s fission reactors are light-water, pressurized-water reactor designs. They don’t produce enough tritium to be recoverable, unless special lithium-containing control rods are inserted, as in the Tennessee Valley Administration reactors. Only a few fission reactors, known as heavy-water reactors, produce substantial and recoverable amounts of tritium.

But, among those heavy-water reactors, not all have the special equipment to extract the tritium from the wastewater. Professor Richard Pearson (Open University, United Kingdom) said that “tritium must be extracted from the heavy-water moderator by means of a Tritium Removal Facility (TRF), of which only two [in the world] are currently in operation, one in Canada and one in South Korea, although there are plans for a third in Romania.” [2]

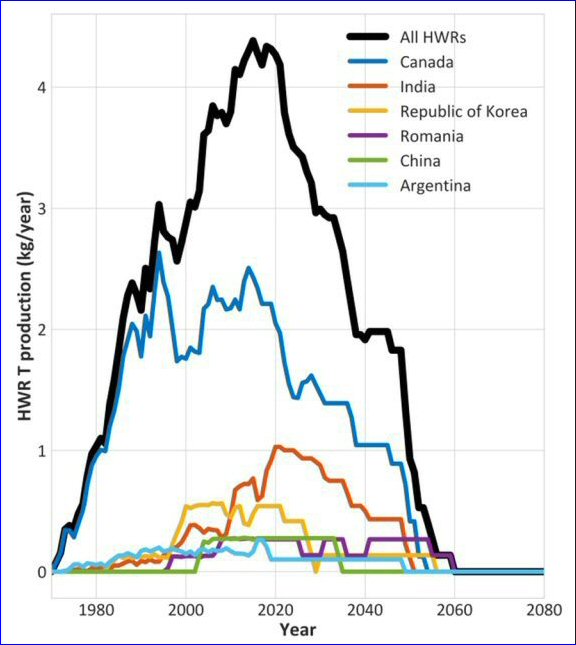

Tritium Issue #3: End-of-Life for Heavy-Water Reactors

Only a handful of countries in the world have heavy-water reactors. Canada has by far the most and is the biggest tritium producer. But its heavy-water reactors, and the others in the world, are approaching or have approached the end of their lifespan. With the possible exception of India, no countries are planning to build new heavy-water reactors.

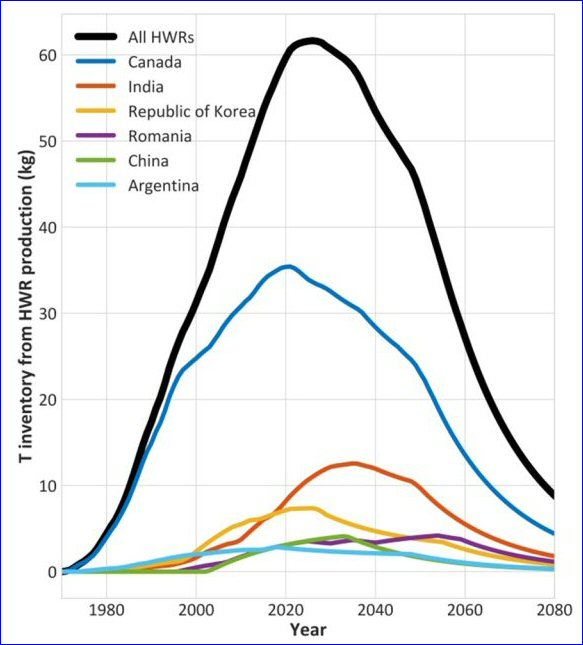

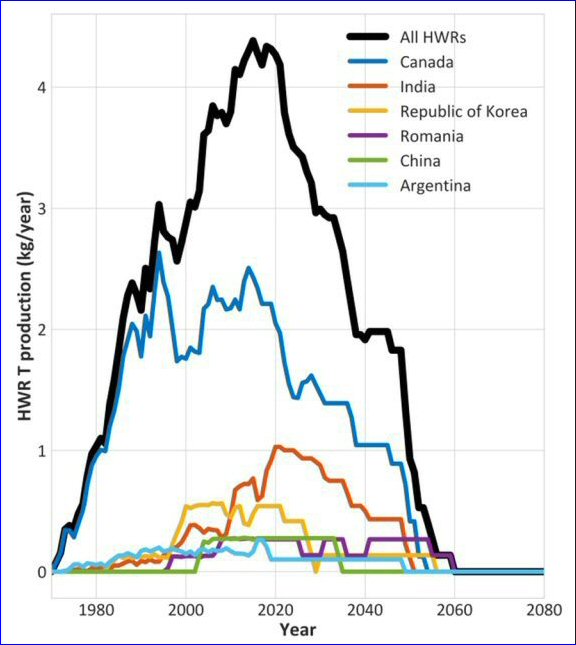

The graph below, by Kovari et al., displays the past and projected worldwide tritium production rates from heavy-water reactors. By 2060, according to the scientists, the global production rate of tritium will reach zero.

Kovari et al. graph of global tritium production

Kovari et al. explained, “It is worth noting that, if scheduled heavy-water reactor refurbishments do not go ahead or, for some reason, heavy-water reactors begin to be phased out earlier than expected across the globe, this would result in almost no tritium being available for fusion experiments.” [3]

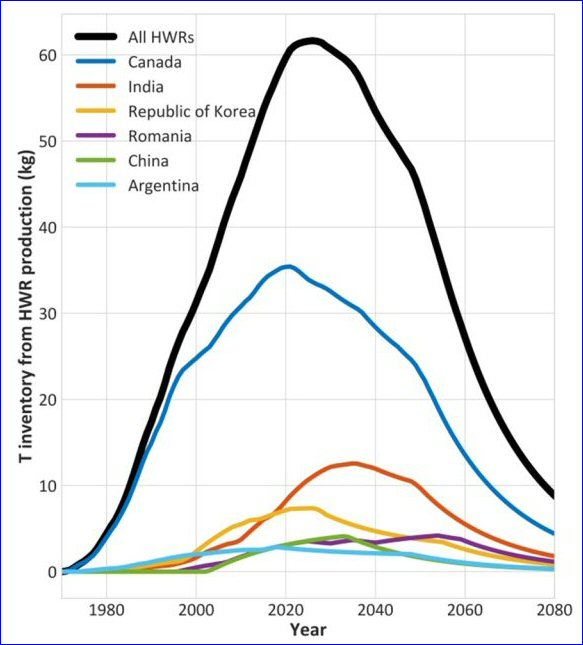

But even after 2060, some tritium will remain in the worldwide inventory. The remaining tritium inventory should be just enough to start — but not to continuously supply — one or maybe two more fusion reactors after ITER. By 2080, as the authors show in the graph below, only 10 kilograms of tritium will remain in the global inventory — assuming it has not been used already for fusion reactors. However, the authors believe that Canada is the only country that sells tritium. So, in effect, only the Canadian tritium inventory would theoretically be available to the worldwide scientific community.

Kovari et al. graph of global tritium inventory

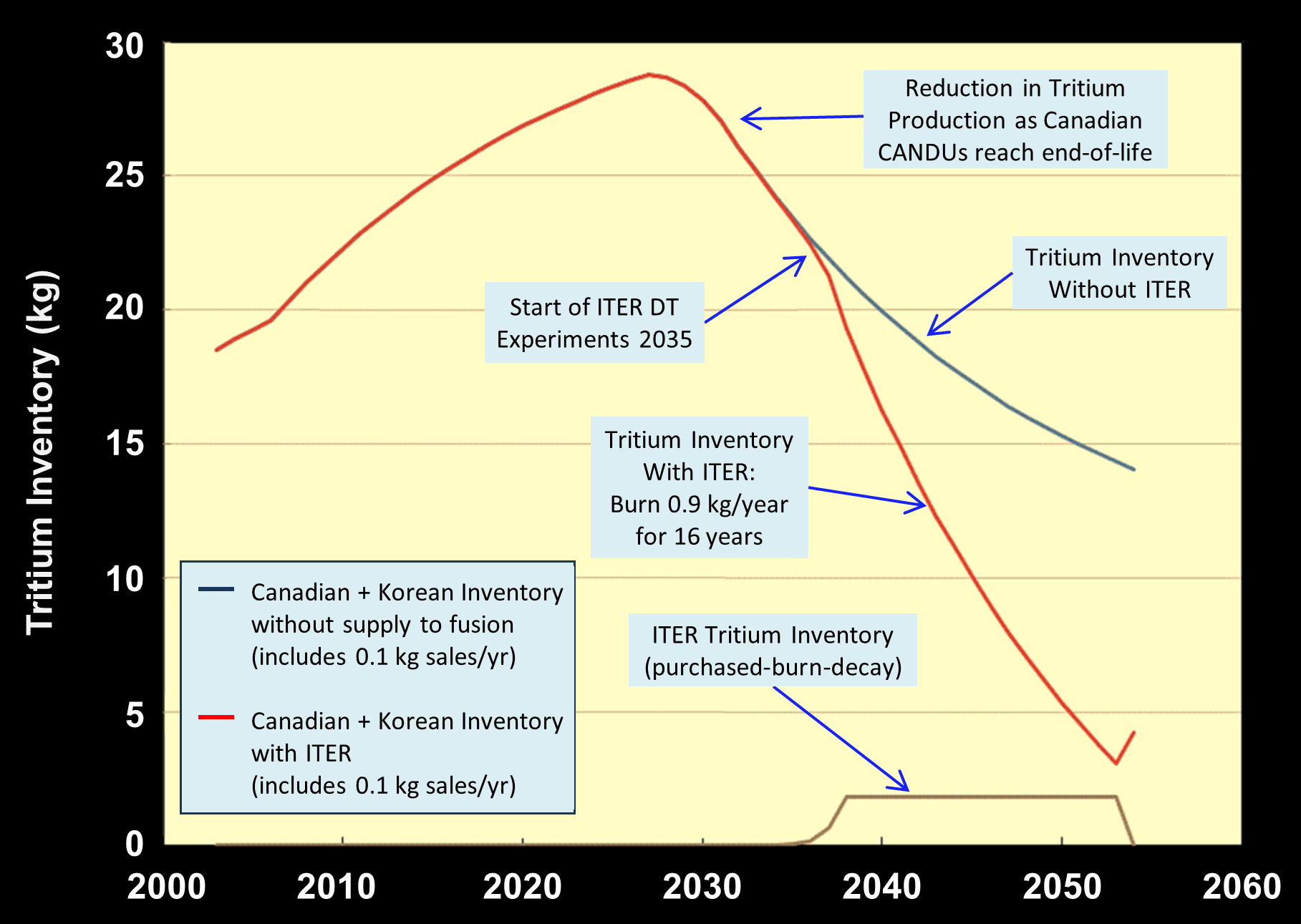

Tritium Issue #4: ITER Will Use Almost the Entire Inventory

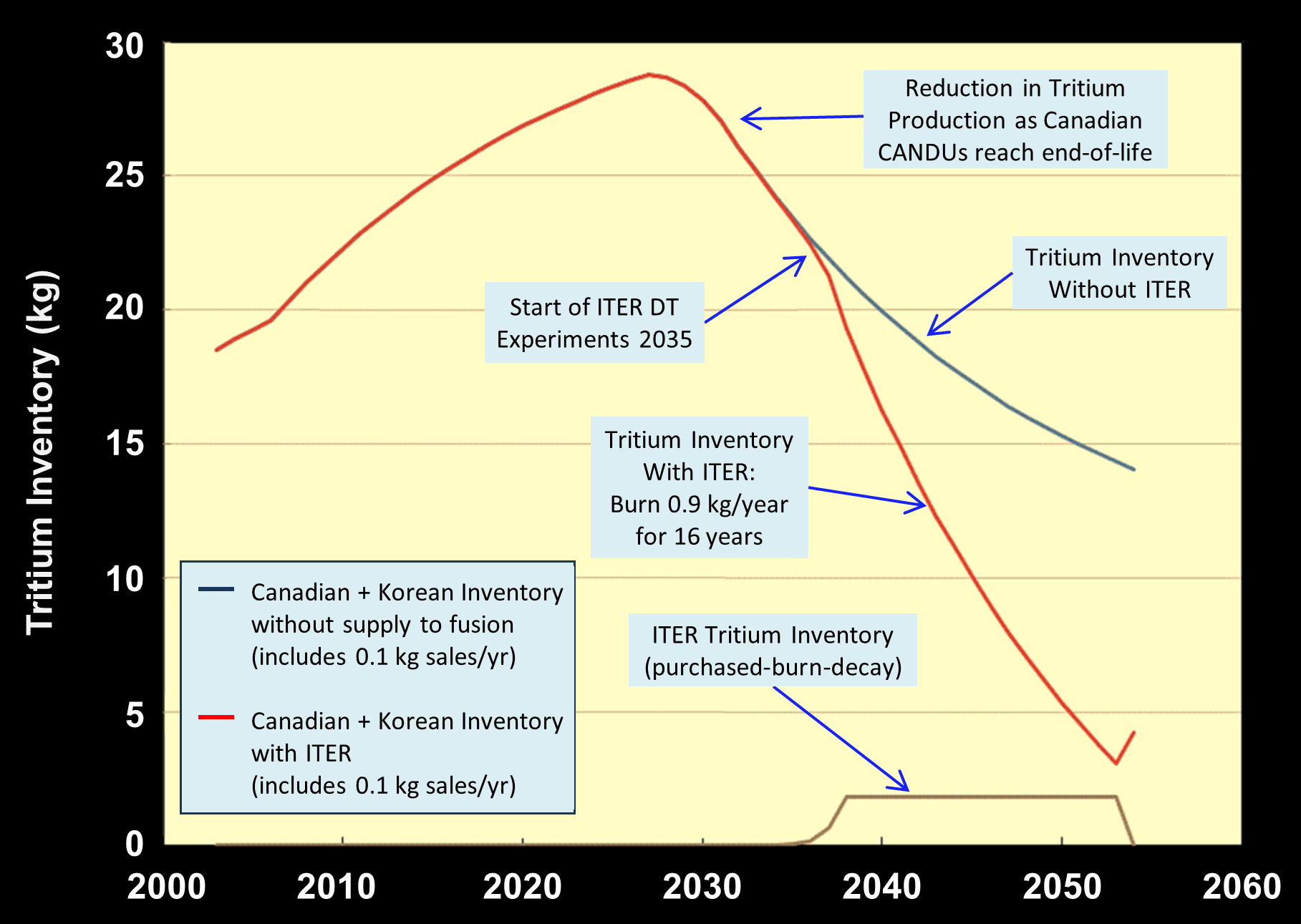

So how much of the global inventory of tritium will ITER consume? At a presentation Abdou gave 14 years ago at the Fusion Energy Sciences Advisory Committee meeting, he said that “a successful ITER will exhaust most of the world supply of tritium.” So the 2080 date is actually irrelevant.

What will the effect of ITER’s tritium consumption on the worldwide tritium inventory look like? Abdou shows us in the graph below. The expected scenario, shown in the red line, from 2035 to 2055, is the global tritium inventory level if ITER does use the expected amount of tritium. In the year 2055, this will bring the remaining global tritium inventory to about three kilograms.

If, for some reason, ITER does not get to its final high-power stage, Abdou calculates the worldwide tritium inventory with the blue line, terminating in the year 2055 at around 14 kilograms.

Graph published by Abdou in many of his slide presentations; labels have been rewritten for clarity.

According to Kovari et al., the amount of tritium required for ITER during its total operating period will be 12.3 kg, which concurs with Abdou’s graph. Kovari et al. wrote, as other fusion tritium experts have done, that the post-ITER tritium scarcity is going to be a serious problem.

The ITER Organization and its closely associated EUROfusion organization, in their public relations programs, imply that a single international DEMO-class reactor will follow ITER.

Image from EUROfusion Web site, Sept. 25, 2021

This helps to maintain the expectation that the costs of the presumed reactor will be shared among the 33 nations that are now partners in the ITER project.

But the ITER partners have no plan for a joint international DEMO reactor and never have had one. If the EU is to build its own DEMO fusion reactor, European taxpayers will have to foot the entire bill. European taxpayers, whether they know it or not, are already paying fusion scientists to design the EU DEMO reactor.

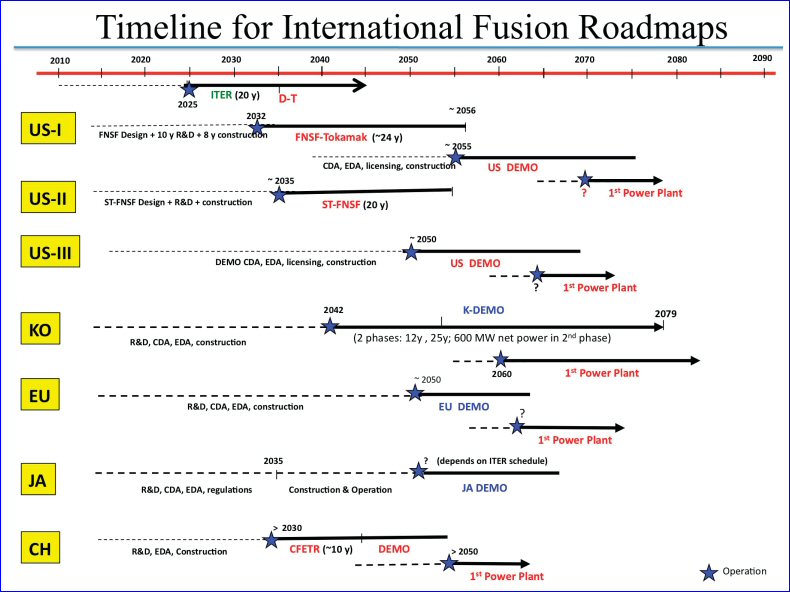

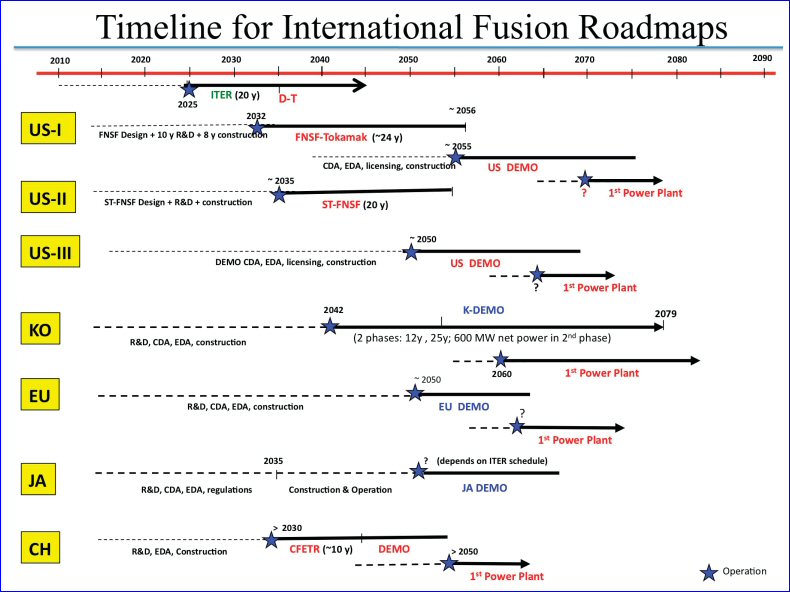

In the 2019 version of “A Strategic Plan for U.S. Burning Plasma Research,” U.S. fusion expert Laila El-Guebaly showed that DEMO-class reactors are in the planning stages from five of the seven ITER partners.

Planned DEMO-class reactors, by Laila El-Guebaly

Kovari et al. provided additional insight into the impending global competition for the last few kilos of tritium on Earth:

There are likely to be serious problems with supplying tritium for future fusion reactors. … If ITER and fusion development are successful, then two or three countries may build their own reactors, giving another major source of uncertainty in tritium requirements. … If Canada, the Republic of Korea, and Romania make their tritium inventories available to the fusion community, there is a reasonable chance that 10 kg of tritium would be available for fusion research in 2055. Stocks would likely have to be shared if more than one fusion reactor is built.

Tritium Issue #5: Fusion Reactors Must Make Their Own Fuel

The solution, fusion scientists propose, is that fusion reactors will make their own fuel. If this sounds too good to be true, skepticism is warranted.

When neutrons react with the element lithium, they produce tritium. Lithium is relatively abundant on Earth as long as there’s no competition from the lithium-ion battery industry.

Fusion scientists have always known that tritium did not exist naturally as a fuel source. They’ve also known for decades that tritium was essential as a fuel component for fusion reactors.

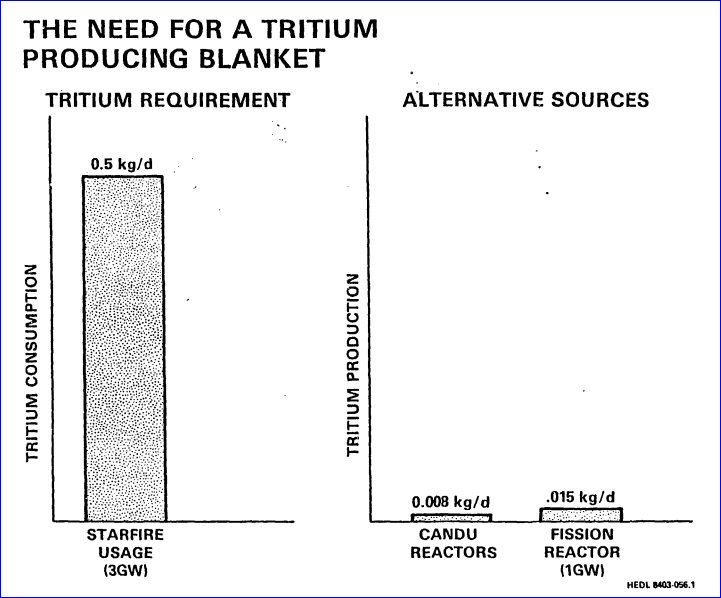

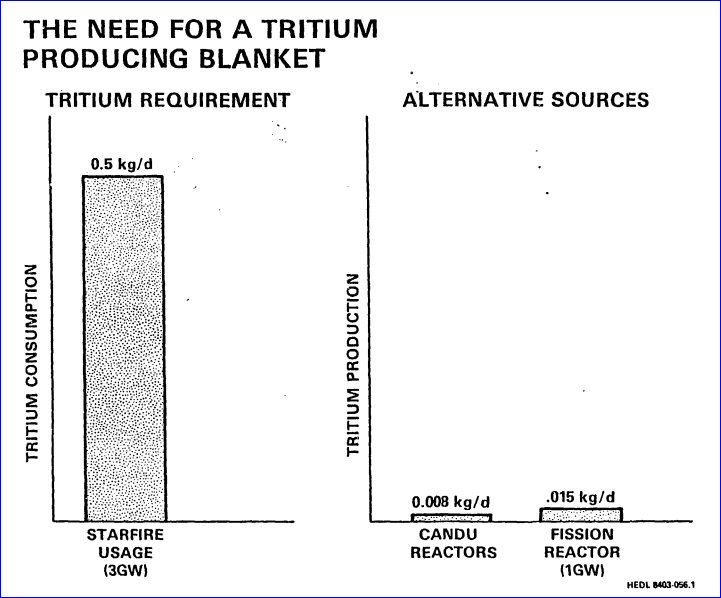

A 1984 conference paper by G.W. Hollenberg explains that fusion reactors will have to make their own tritium: “The on-site production of tritium at a fusion power plant is an established design practice for D-T fusion reactors; no other alternative is envisioned.”

The Hollenberg document refers to a DEMO-class reactor that U.S. fusion scientists envisioned 40 years ago called Starfire. The bar on the left shows how much tritium they expected the reactor to consume every day. The bars on the right show how much tritium they expected worldwide fission reactors could provide. One of the authors was Abdou; he’s been at this a long time.

Starfire tritium requirements, G.W. Hollenberg et al., 1984 (See 10/17/21 notes)

Tritium Issue #6: Tritium Self-Sufficiency

Because virtually no commercially available tritium will be available in the world after ITER, all fusion reactors planned for operation after ITER will need to be tritium self-sufficient. This means that fusion reactors not only will have to make their own tritium fuel but also won’t be able to get tritium from any outside sources. This is what it means for fusion reactors to be tritium self-sufficient.

People like Abdou have been trying for decades to resolve by calculations and computer modeling whether the achievable rate of tritium that can be produced in a fusion reactor will be sufficient for the continued operation of a fusion reactor.

According to Jassby, only one physical experiment in fusion research history has attempted to breed tritium in a fusion reactor. It was Jassby’s experiment, performed in 1995-1996 in the Princeton Tokamak Fusion Test Reactor. His experiment showed that the total amount of tritium produced in a breeding medium just outside the TFTR vacuum vessel was only 32 percent of the total number of fusion neutrons intersected by that medium [4].

But even if a fusion reactor produces tritium at a rate of 100 percent of the tritium it requires to operate, fusion is a dead end. A reactor has to produce tritium at a higher rate than it consumes tritium in order to compensate for inefficiencies and downtime. According to a Jan. 27, 2020, presentation from Abdou, a fusion reactor would need to produce about 112 percent of the tritium it will consume in order to continue operating.

So, is a production rate (technically known as the tritium breeding ratio) of 112 percent achievable? In a scientific article that Abdou and eight co-authors published recently, they said they don’t know. They said that they have high confidence that a rate of 105 percent is achievable but that they have less confidence that a rate of 115 percent can be realized. The fate of the worldwide effort to commercialize nuclear fusion rests on this razor-thin edge of a few percentage points. But, as the authors wrote, the data are not favorable. [5]

The authors concluded that, based on known physics and state-of-the-art technology, fusion reactors following ITER will not be able to breed enough tritium to be self-sufficient.

Here is exactly what the authors said at the beginning of their abstract:

![Excerpt from Abdou et al. 2020 abstract [5]](http://newenergytimes.com/v2/sr/iter/tech/Abdou-2020.jpg)

Excerpt from Abdou et al. 2020 abstract [5]

Tritium Issue #7: Tritium Start-Up Inventory

Even if a tritium breeding-ratio issue is solved, there’s one more problem. Where will a reactor get the tritium it needs in order to start up? Will the few remaining kilograms of global tritium after ITER be enough? Which country is going to acquire that tritium? The grim reality, according to Kovari et al., is that there may not be enough tritium to start even one DEMO-class reactor:

The tritium available commercially from the Canadian reactor production program after the retirement of ITER may not be sufficient to start [the EU] DEMO. Two factors make the tritium supply for [the EU] DEMO even smaller than previously considered. First, ITER will be severely delayed, and if [the EU] DEMO is similarly delayed, then all the Canadian CANDU reactors will have been shut down, while the civilian tritium stockpile will have undergone decay.

Are there any alternatives? Is it as bad as it seems? Can’t deuterium-deuterium fusion reactions produce tritium? Yes, they can, and Kovari et al. answered this question.

“It is, in theory, possible to start up a fusion reactor with little or no tritium, but at an estimated cost of $2 billion per kilogram of tritium saved, it is not economically sensible,” Kovari et al. wrote.

Why is a cost saving of only $2 billion per kilogram not economically sensible? Because, as the authors wrote, the interest payments alone for the construction costs of the reactor during the time when it’s building up an inventory of tritium and generating zero power would be $6 billion.

Will ITER Breed Tritium?

One final matter needs to be clarified: Will ITER breed its own tritium? One scientist who is capable of answering this question is Tony Donné, the head of the EUROfusion organization. His organization is funded by the EU and is responsible for the design activities for the EU DEMO reactor.

The EU DEMO reactor is expected to use lithium throughout the entire interior structure of the reactor in order to breed the tritium it needs to operate. But ITER will have no such lithium blanket. Here’s what Donné told me about tritium breeding in ITER:

ITER will test four different technologies to breed tritium. So it will actually breed tritium but less than is needed for its own consumption. The experiments in ITER will give guidance to the technologies to be used in DEMO, which is envisaged to have a tritium breeding ratio greater than 1 and, hence, produce its own tritium.

Then I asked Abdou, and I received a very different answer:

ITER is not designed to breed tritium, and it will not breed tritium. ITER has only limited mockup testing of some breeding blanket concepts. The amount of tritium to be produced in these mockups is small and cannot provide a significant fraction for ITER to use. The mockup is a simulation of a blanket module about one square meter of surface area facing the plasma. There will be only four of these. ITER has about 600 square meters of surface area. So all the test mockups cannot produce more than 1 percent of ITER’s tritium consumption, at the best conditions.

Summary of the Tritium Issues

- A fusion reactor with a full tritium breeding blanket must be able to achieve a minimum tritium breeding ratio of 1.12, despite the fact that experts do not know how this will be possible.

- The global inventory of tritium must be large enough to start at least the first DEMO-class fusion reactor.

- The first DEMO-class fusion reactor must go into operation before the last of the tritium inventory disappears.

- If successful, the first DEMO-class fusion reactor must be able to produce enough tritium to start the second DEMO-class fusion reactor, and so on.

The only other solution is that the world needs to build new heavy-water fission reactors to produce fuel for fusion reactors. To borrow from “The Matrix,” “fate, it seems, is not without a sense of irony.” Fusion scientists have been bashing fission reactor technology for decades.

Next: The Fusion Fuel Discrepancy: The Misleading Claims

References

- Mohamed Abdou, NAS Committee in La Jolla, Calif., Feb. 26, 2018

- Richard J. Pearson, Armando B. Antoniazzi, William J. Nuttall, “Tritium Supply and Use: A Key Issue for the Development of Nuclear Fusion Energy,” Fusion Engineering and Design, (May 31, 2018) 136, (B), 1140-1148

- Kovari, M. Coleman, I. Cristescu, and R. Smith, “Tritium Resources Available for Fusion Reactors,” (Dec. 21, 2017) Nuclear Fusion, 58 (2)

- L. Jassby, C.A. Gentile, G. Ascione, H.W. Kugel, A.L. Roquemore, and A. Kumar, “Tritium Production in He-3 Gas cells Immersed in the Tokamak Fusion Test Reactor Neutron Field,” (1999) Review of Scientific Instruments 70, 1115-1118

- Mohamed Abdou, Marco Riva, Alice Ying, Christian Day, Alberto Loarte, L.R. Baylor, Paul Humrickhouse, Thomas F. Fuerst and Seungyon Cho, “Physics and Technology Considerations for the Deuterium-Tritium Fuel Cycle and Conditions for Tritium Fuel Self Sufficiency,” (Nov. 23, 2020) Nuclear Fusion, 61 (1)

Oct. 17, 2021 Notes: A reader asks: In the Abdou chart it says ITER will burn 0.9kg of tritium per year. In the Starfire chart, it says Starfire would burn 0.5kg per day. That’s about 203 times more than ITER. Why were these tritium consumption numbers are so far apart? Daniel Jassby answers: Starfire was supposed to operate continuously. ITER will have, at most, 1,000 pulses of 400 sec length. 400,000 sec is about 1% of a year. The projected ITER fusion power is about 20% of the Starfire fusion power. There you have a factor of 500.

Thanks to Daniel Jassby for pointing out the following clarification about the alternative tritium sources shown in this graph. Hollenberg et al. show the CANDU tritium production rate at 2.9 kg/year per GW of electric power. According to Jassby, a single CANDU reactor produces 0.2 kg of tritium/yr/GW as an unintended byproduct. Thus, the Hollenberg et al. 1984 value assumes a quantity of 10 tritium-producing CANDU reactors. Hollenberg et al. show the tritium production rate from special light-water reactors, which must be intentionally equipped to breed tritium, at 5.4 kg/yr/GW. According to Jassby, a single such reactor produces at most, 2 kg/yr/GW of tritium. Thus, the Hollenberg et al. value assumes a quantity of 3 such reactors.

![Excerpt from Abdou et al. 2020 abstract [5]](http://newenergytimes.com/v2/sr/iter/tech/Abdou-2020.jpg)