Johannes Schwemmer, Director of Fusion for Energy

Return to ITER Power Facts Main Page

By Steven B. Krivit

July 23, 2020

The European ITER domestic agency known as Fusion for Energy recently published new false claims about the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor project known as ITER. The project will cost taxpayers from 35 nations $45 billion.

The reactor is not designed to produce electricity. However, if it works as planned, it will demonstrate an important scientific achievement: a fusion plasma that has more thermal power than the thermal power used to heat the fuel.

Practically speaking, however, this means that the reactor will produce about zero net power output and will not demonstrate that fusion is a viable energy source despite the hype.

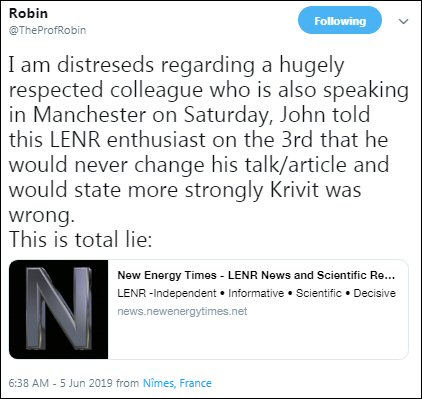

Even though Johannes Schwemmer, the director of the agency, knows how to make accurate and honest claims about the ITER reactor, his organization published a new set of inaccurate, misleading, and exaggerated claims several months ago in three places on the Fusion for Energy ITER Web page.

When fusion scientists talk to one another, they all understand the objective of the ITER project. But when they are communicating the project’s goals to the public, some scientists make false and misleading claims about ITER.

In his own words, from his Nov. 9, 2018, letter to me, Schwemmer wrote that the accurate way to represent the primary objective and goal of ITER is to “ensure that there is no possible misunderstanding on the ITER energy gain of 10 – [that it is] linked only to the plasma and not to the energy balance of the overall ITER plant.”

Yet his organization does otherwise.

CLAIM #1

CLAIM #1: CURRENT STATEMENT

“ITER, which in Latin means ‘the way,’ will be the world’s biggest experiment on the path to fusion energy. It will be the first fusion device to generate more energy than that it consumes.”

NOTE: This is false: The device itself is expected to demonstrate zero net power; see the power values in detail below.

An accurate statement would be “ITER, which in Latin means ‘the way,’ will be the world’s biggest experiment on the path to fusion energy. It will be the first fusion device to produce a fusion plasma with more thermal power than the heating power injected into the plasma.”

CLAIM #2 CURRENT STATEMENT

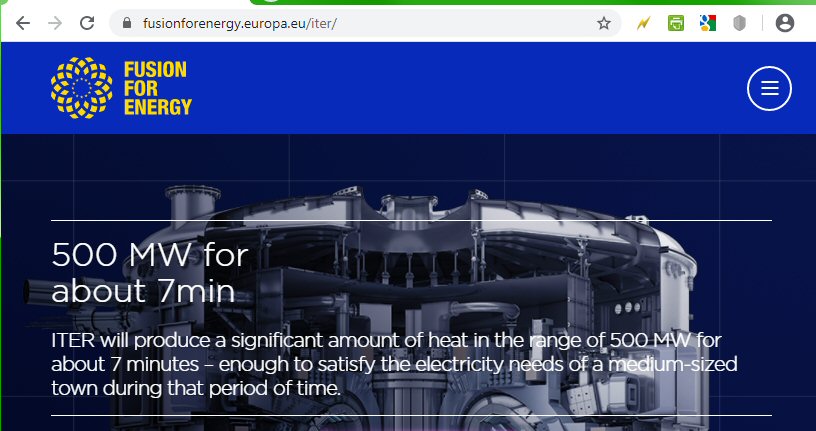

“500 MW for about 7 min – ITER will produce a significant amount of heat in the range of 500 MW for about 7 minutes – enough to satisfy the electricity needs of a medium-sized town during that period of time.”

NOTE: This is dishonest and misleading: If ITER were designed to convert the net thermal power output to electricity, there wouldn’t be enough net power to produce 1 Watt. Based on the ITER design, the overall reactor will produce 686 MW gross thermal output. If this were converted to electricity, it would result in 274 MW gross electrical power and negative 26 MW net electrical power.

An accurate statement would be “A 500 MW plasma for about 7 min – ITER will produce a fusion plasma with a significant amount of thermal power in the range of 500 MW for about 7 minutes.”

CLAIM #2

CLAIM #3 CURRENT STATEMENT

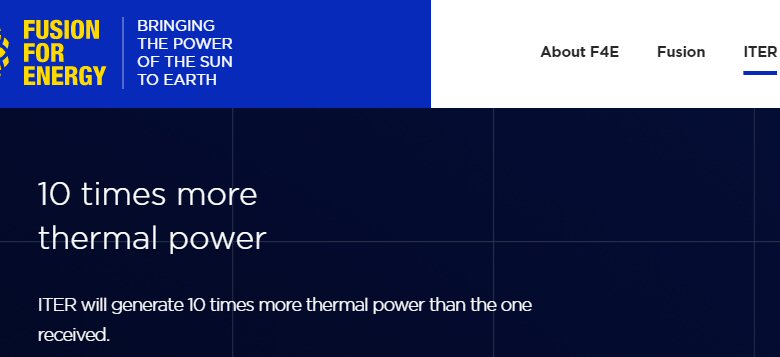

“10 times more thermal power – ITER will generate 10 times more thermal power than [that] received.”

NOTE: This is misleading. To be accurate, all power claims must clearly be associated with the plasma.

An accurate statement would be “ITER will produce a fusion plasma with 10 times more thermal power than the heating power injected into the plasma.”

CLAIM #3

In other news, the European Parliament just approved another €5 billion for the ITER project.

Fusion for Energy Governing Board (July 23, 2020)

Beatrix Vierkorn Rudolph — Chair of the Governing Board of Fusion for Energy

Friedrich Aumayr — Director, Institute of Applied Physics TU Wien (Vienna University of Technology), Austria

Daniel Weselka — Head of Unit, Federal Ministry for Science and Research, Austria

Ir Alberto Fernandez Fernandez — Nuclear Attaché to DG Energy, FPS Economy, Belgium

Eric Van Walle — General Manager, SCK.CEN, Belgium

DSC Troyo Dimov Troev — Head of Research Unit of the Association Euratom-INRNE, Bulgaria Academy of Sciences, Bulgaria

Tonci Tadic — Division of Experimental Physics, Laboratory for Ion Beam Interactions, Rudjer Boskovic Institute, Croatia

Stjepko Fazinic — Division of Experimental Physics, Laboratory for Ion Beam Interactions, Rudjer Boskovic Institute, Croatia

Anastassios Yiannaki — Director of Reactor Services Division Nuclear Research Institute Rež, Cyprus

Radomir Panek — Institute of Plasma Physics of the CAS, Czech Republic

Ing. Ladislav Vála — Senior Researcher & Project Manager Centrum výzkumu Rež s.r.o. (Research Centre Rež), Czech Republic

Tomas Midtgaard — Senior Advisor, Danish Agency for Science, Technology and Ministry of Higher Education and Science, Denmark

Volker Naulin — Head of Section, Plasma Physics and Fusion Energy, Department of Physics, Technical University of Denmark, Denmark

Rein Kaarli — Advisor, Department of Research, Ministry of Education and Research, Estonia

Madis Kiisk — Director, Institute of Physics, University of Tartu, Estonia

Tuomas Tala — Head of Research Unit of the Euratom-Tekes Association, VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, Finland

Kari Koskela — Senior Advisor, Centre for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment for Southeast Finland, Finland

Bertrand Bouchet — Managing Director for European Affairs CEA- International Relations Division, France

Maria Faury — Director of international affairs and large research infrastructures, CEA – Fundamental research division, France

Harald Bolt — Forschungszentrum Juelich (VS-U), Germany

Michael Stötze — Head of Division “Fusion Research: FZJ, HZDR, HZB, IPP” Federal Ministry of Education and Research, Germany

Stubos Athanasios — Director of the Institute of Nuclear and Radiological Sciences and Technology, Energy and Safety. National Centre for Scientific Research Demokritos, Greece

Mergia Konstantia — Director of Research, INRASTES, NCSR Demokritos Scientist in charge of Greek Fusion Technology Program for Demokritos, Greece

Siegler Andras — Senior Advisor National Research Development and Innovation Office Hungary, Hungary

Gábor Veres — Wigner Research Centre for Physics, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Hungary

Miles Turner — Physics, Dublin City University, Ireland

Paul Shortt — Dept. of Communications, Climate Action and Environment, Ireland

Ing Aldo Pizzuto — Head of Research Unit Euratom-ENEA Association, ENEA Frascati, Italy

Eugenio Nappi — Vice President INFN, Italy

Massimo Garribba — Director of Nuclear energy, safety and ITER, DG Energy European Commission, EURATOM

Dmitrijs Stepanovs — Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Latvia, Latvia

Hab Andris Sternbergs — Institute of Solid State Physics, University of Latvia, Afghanistan

Sigitas Rimkevicius — Head, Laboratory of Nuclear Installation Safety Lithuanian Energy Institute, Lithuania

Stanislovas Žurauskas — Deputy Head, Science and Technology Division, Ministry of Education and Science, Lithuania

Leon Diederich — Conseiller de Gouvernement, Ministere de l’Enseignement superieur et de la Recherche, Luxembourg

Gaston Schmit — Conseiller de Gouvernement, Ministere de l’Enseignement superieur et de la Recherche, Luxembourg

Ian Gauci Borda — Associate Consultant, Malta Council for Science and Technology, Malta

Karl Montebello — Policy and Strategy Executive, The Malta Council for Science and Technology, Malta

Jeannette Ridder-Numan — Senior policy advisor/deputy head for Science and Humanities and International Affairs, Ministery of Education, Culture and Science, Netherlands

Marco de Baar — Director Nuclear Fusion Programme DIFFER institute, Netherlands

Lukasz Ciupinski — Scientific Expert Materials Design Division, Faculty of Materials Science and Engineering Warsaw University of Technology, Poland

Paulina Styczen — Principal Expert, Department of Strategy, Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Poland, Poland

Carlos Varandas — Instituto de Plasmas e Fusao Nuclear, Portugal

Teresa Ponce de Leão — President of LNEG, Portugal

Florin Buzatu — Director-General, Institute of Atomic Physics, Romania

Teddy Craciunescu — National Institute of Lasers, Plasma and Radiation Physics NILPRP Bucharest-Magurele, Romania, Romania

Stefan Matejcik — Faculty of Mathematics, Physics and Informatics, Comenius University, Slovakia

Jozef Pitel — Research Scientist, Institute of Electrical Engineering, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Slovakia

Jože Duhovnik — Dean, Faculty for ME, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia

Igor Lengar — Jozef Stefan Institute, Reactor Physics Division, Slovenia

Joaquín Sánchez Sanz — Director de Laboratorio Nacional de Fusion Centro Investigaciones Energéticas, Medioambientales y Tecnológicas (CIEMAT), Spain

Carlos E. Martínez Riera — Ministry of Sciencie, Innovation and Universities, Spain

James Drake — Division of Fusion Plasma Physics, The Royal Institute of Technology KTH, Sweden

Pär Omling — Department of Solid State Physics, Lund University, Sweden

Xavier Reymond — State Secretariat for education, Research and Innovation, International Cooperation in Research and Innovation, Switzerland

Ambrogio Fasoli — Director Centres de Recherches en Physique des Plasmas CRPP Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne EPFL, Switzerland