Return to ITER Power Facts Main Page

By Steven B. Krivit

September 9, 2021

Yesterday, Declan Kirrane, one of the organizers of a science summit for the 76th United Nations General Assembly, taking place Sept. 14-30, cancelled the summit’s scheduled session on nuclear fusion.

Several months ago, Kirrane approached Michel Claessens, one of two former spokesmen for the ITER organization, and asked him to help organize the fusion session for the summit. Kirrane was scheduled to be the chair of one panel. Claessens, the author of the book ITER: The Giant Fusion Reactor: Bringing a Sun to Earth, was scheduled to be the chair of the other panel.

Yesterday, Kirrane wrote to Claessens that the ITER organization decided not to participate in the program. Kirrane quickly began learning about the conflicts.

“This morning I had contact with the ITER organization. I learned that you and they have some differences of views. ITER will not participate in any meeting or activity that you have anything to do with. I have therefore decided to cancel the UNGA76 session on nuclear fusion,” Kirrane wrote.

Rather than accommodate the ITER organization’s implicit demand, Kirrane cancelled the entire session.

Even before he left the ITER organization in 2015, Claessens was concerned about the integrity of the organization’s public claims.

In 2017, when he was working for the European Commission, he learned more details about the previously hidden reactor power values and encouraged an open, public discussion. Claessens told New Energy Times that Laban Coblentz, the current ITER organization spokesman, immediately began encouraging Claessens to shut up.

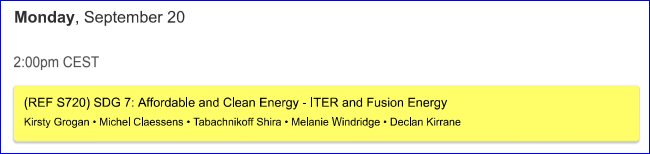

Planned panelists for “Can ITER and Fusion Energy Play a Role in Fighting Climate Change?”

Panel Moderator: Declan Kirrane

Shira Tabachnikoff (deputy head of communications for the ITER organization)

Melanie Windridge (spokeswoman for Tokamak Energy Ltd., and the U.K. spokeswoman for the Fusion Industry Association)

Kirsty Gogan (managing partner of LucidCatalyst)

Samuele Furfari (chemical engineer at Université Libre de Bruxelles)

Planned panelists for “Will Fusion Energy Become Commercial Before 2050?”

Panel Moderator: Michel Claessens

Bernard Bigot (director-general of ITER Organization)

Michel Laberge (chief scientist at General Fusion)

Bob Mumgaard (founder and chief executive officer of Commonwealth Fusion Systems)

Mark Henderson (United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority)

Bigot is featured in the documentary film ITER, The Grand Illusion: A Forensic Investigation of Power Claims.

Laberge, Mumgaard, and Henderson are featured in the investigative analysis “When Will We Get Energy From Nuclear Fusion?”

Henderson is featured in the Public Broadcasting Radio program “A Fusion Experiment Promised to be the Next Step in Solving Humanity’s Energy Crisis. It’s a Big Claim to Live up To”

Affordable and Clean Energy

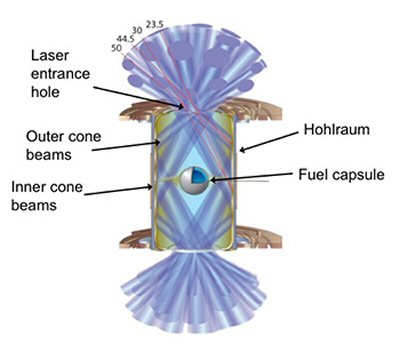

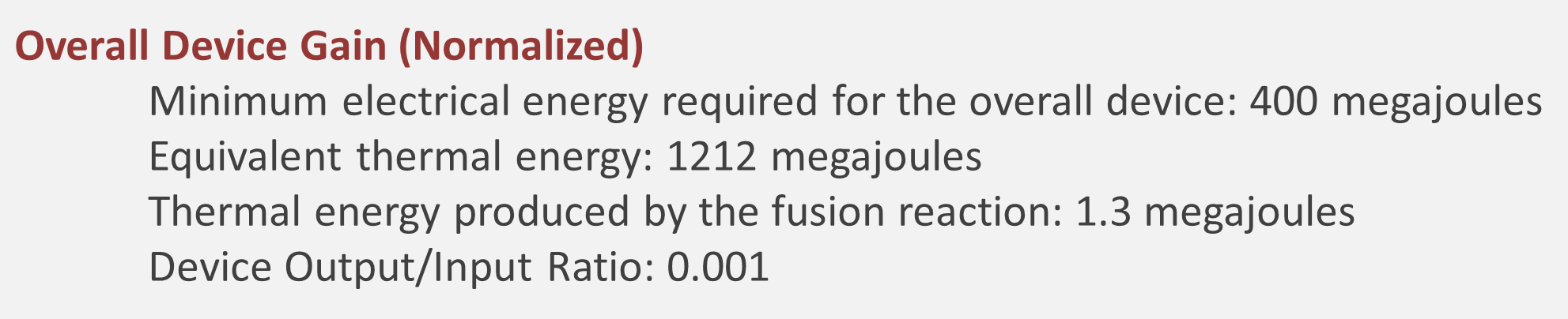

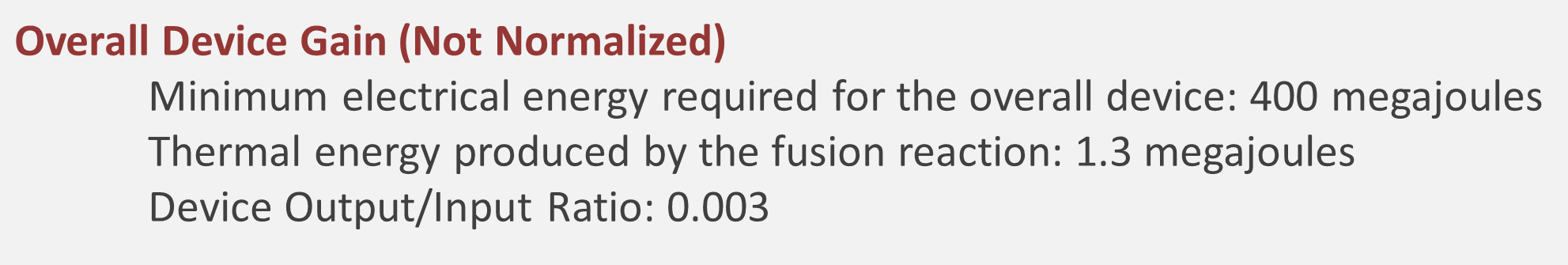

ITER is a $65 billion science experiment that, if successful, will inject 50 million Watts of thermal power into the fusion fuel and, in turn, produce fusion reactions with 500 million Watts of thermal power. The experiment is designed to run for 500 seconds and scientists hope it will achieve its peak 500 MW output sometime around 2045.

If ITER succeeds in this, its primary scientific goal, the correlated result for the overall reactor will be an equivalent loss of about 250 million Watts of thermal power. The equivalent loss, normalized to electric power, will be 100 million Watts.

In some universe, this may prove that fusion is an affordable, commercially viable form of clean energy. But not ours.

Promoters of fusion have been claiming that commercial fusion energy is “right around the corner” for most of the last 70 years of the global fusion research program. Despite an overwhelming array of recent designs on paper, magnificent-looking devices, and the generous contributions by private investors, not one fusion reactor has ever produced a single Watt of thermal power in excess of the electricity required to operate the reactor. In light of the complete absence of experimental evidence that a fusion reactor can produce net energy, and in light of the overwhelming presence of false and misleading claims, fusion research has more potential to become the world’s biggest science scam than a practical source of energy.

Records for Science Summit for the 76th United Nations General Assembly

List of fusion sessions (Retrieved Sept. 8, 2021)

Summit Schedule (Retrieved Sept. 8, 2021)

Summit Schedule (Retrieved Sept. 9, 2021)

Sept. 12, 2021 Update: Details about the background conflict have been added.