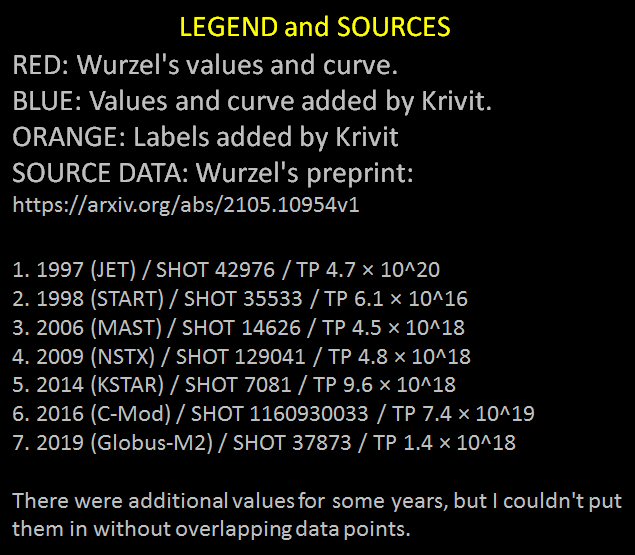

Laban Coblentz, the current ITER organization spokesman speaking at press conference last year

Return to ITER Power Facts Main Page

By Steven B. Krivit

Nov. 3, 2021

Cliquez ici pour la version française de cet article.

Also published today:

ITER Director-General Makes False Power Claim to French Senate

Bernard Bigot Presentation to the French Senate – Last 3 Minutes

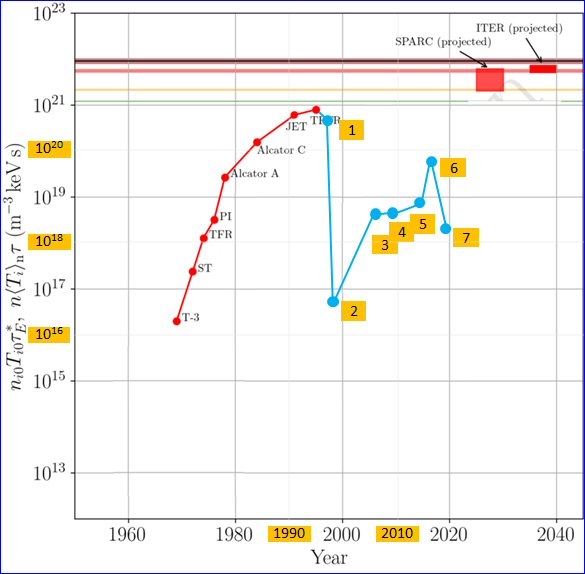

The ITER organization has confirmed that the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor is not designed to produce net power. This disclosure comes four years after articles in New Energy Times revealed that the ITER design is equivalent to a zero-net-power reactor.

In an article in the French newspaper Le Canard Enchainé last week, Michel Claessens, the former ITER organization spokesman, explained the ITER power discrepancy.

“For many years, it was claimed that the reactor will generate ten times the power injected. It is completely wrong. Thanks to a patient investigation, the American journalist Steven Krivit showed that ITER will consume as much [power] as it will generate,” Claessens said. “We know now that the net [power] balance will be close to zero.”

The newspaper asked the ITER organization for a response. The organization sent an official but unsigned response, provided under the direction of the current ITER spokesman, Laban Coblentz.

“It is obvious that all the systems of the ITER installation will consume more energy than produced by the plasma,” the ITER organization said.

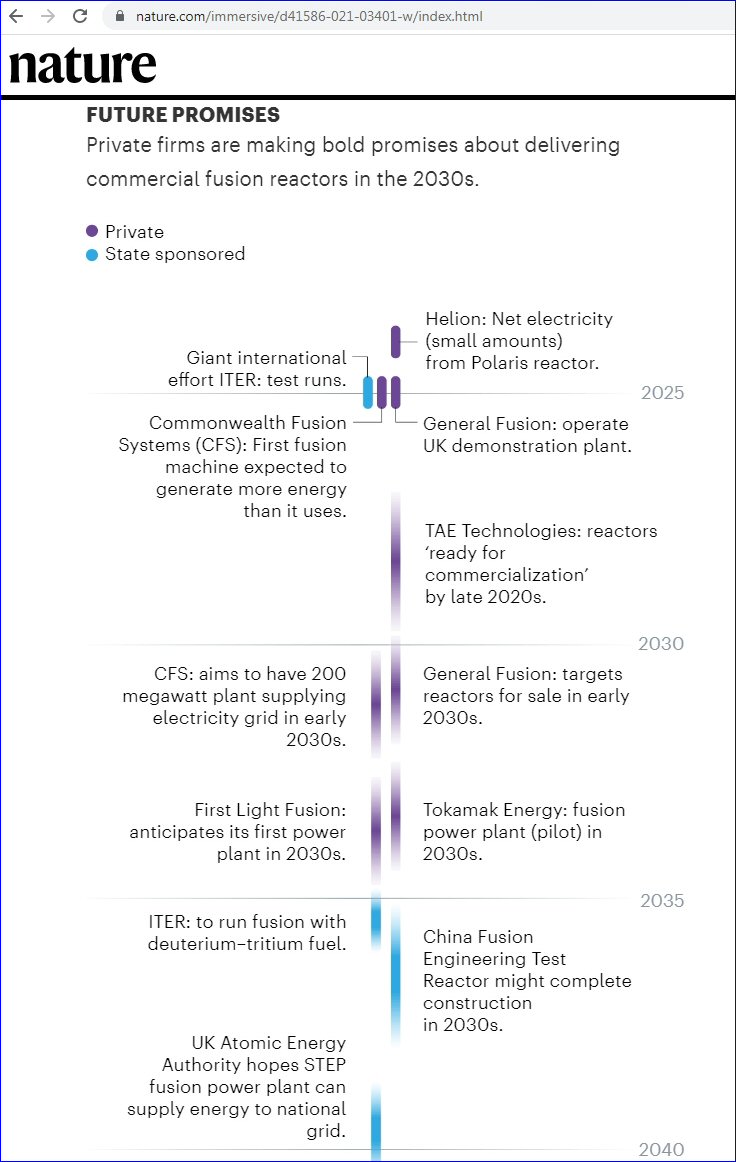

To the contrary, the widespread understanding, as shown by these citations from academic institutions, fusion industry partners, government agencies, energy organizations, encyclopedia articles, and the news media, has been that the overall reactor system is designed to produce net power. Here are a few examples:

- “[ITER’s] design is a scaled-up version of JET, and the scientists here want to produce 500 megawatts of power, 10 times its predicted input.” (The Guardian, Jan. 25, 2015)

- “ITER should be completed in 15-20 years and claims to deliver 500 MW of power, about the same as today’s large fission reactors.” (The Guardian, Oct. 17, 2016)

- “The plan is to create 500 megawatts of usable energy from an input of 50 megawatts.” (New Scientist, June 15, 2021)

- “The energy released by the machine should be roughly ten times the power it consumes.” (Nature, May 6, 2010)

- “If all goes to plan, ITER will release ten times the power it consumes, sometime after 2026.” (Nature, Nov. 12, 2010)

- “[ITER] an experimental reactor designed to use nuclear fusion to generate ten times the power that is put in.” (Nature, July 31, 2014)

- “[ITER] is predicted to produce about 500 megawatts of electricity.” (Nature, May 26, 2016)

- “Although all fusion reactors to date have produced less energy than they use, physicists are expecting that ITER will benefit from its larger size, and will produce about 10 times more power than it consumes.” (New York Times— March 27, 2017)

- “ITER aims to produce 500 megawatts of power, 10 times the amount needed to keep it running.” (Science, Oct. 13, 2006)

- “The international demonstration is aiming to generate about 10 times its input power.” (Science, 21, 2017)

- “ITER aims to be the first tokamak to produce more energy than it consumes. But TFTR was also supposed to do that and it came up short.” (Science, 6, 2020)

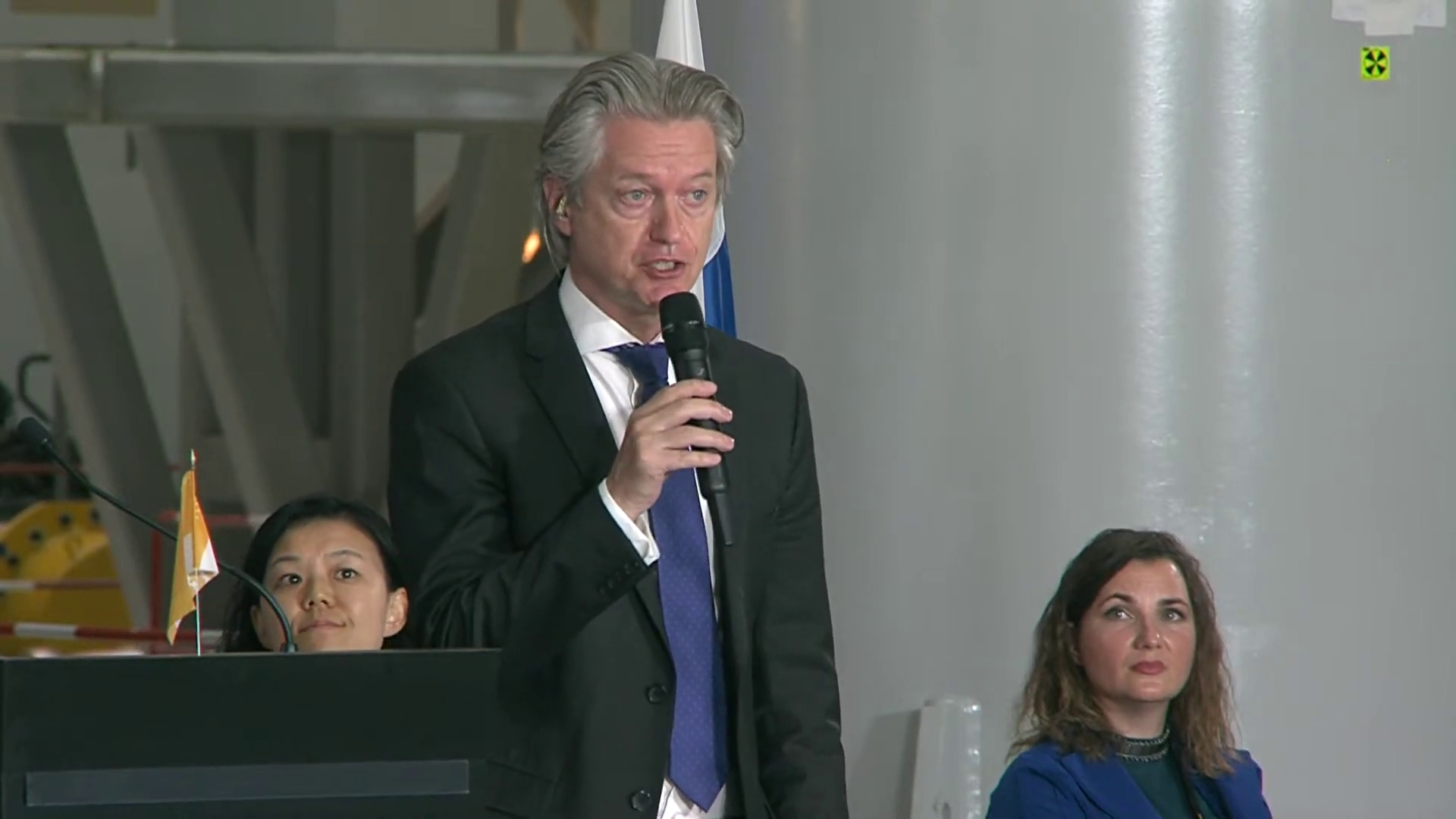

The Long History

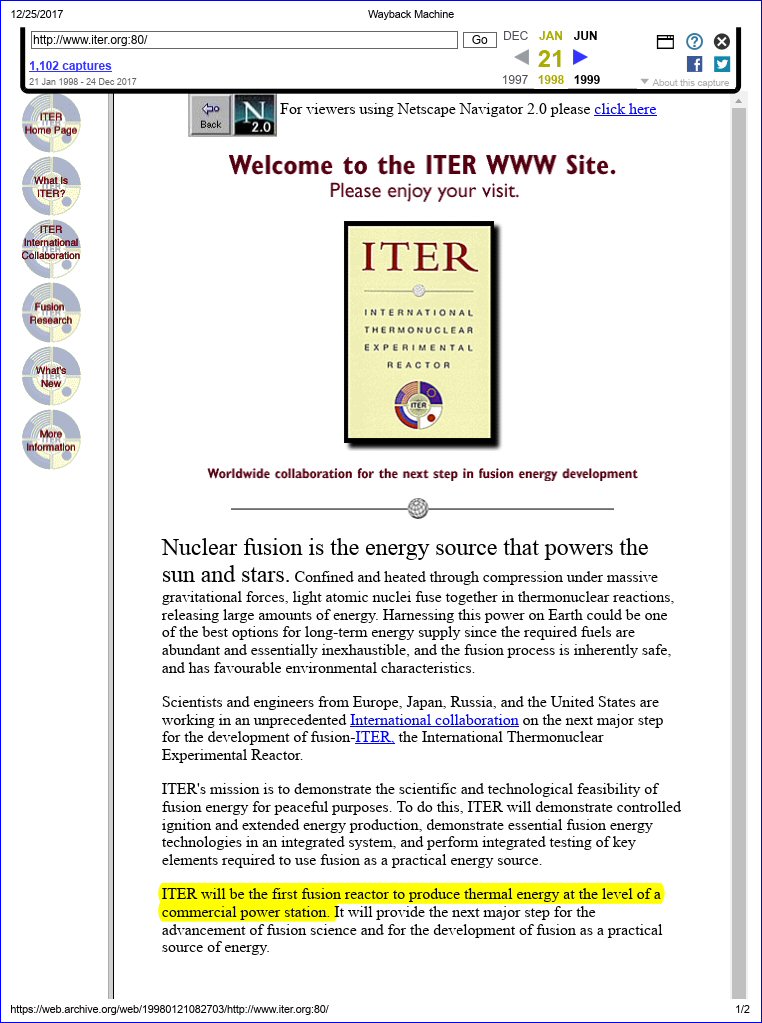

The false notion that the ITER reactor is designed to produce more power than it consumes goes back decades. A screen capture of the organization’s Web site from Jan. 21, 1998, shows that the organization said that “ITER will be the first fusion reactor to produce thermal energy at the level of a commercial power station.”

Image capture of ITER organization home page, Jan. 21, 1998 (Courtesy Archive.org)

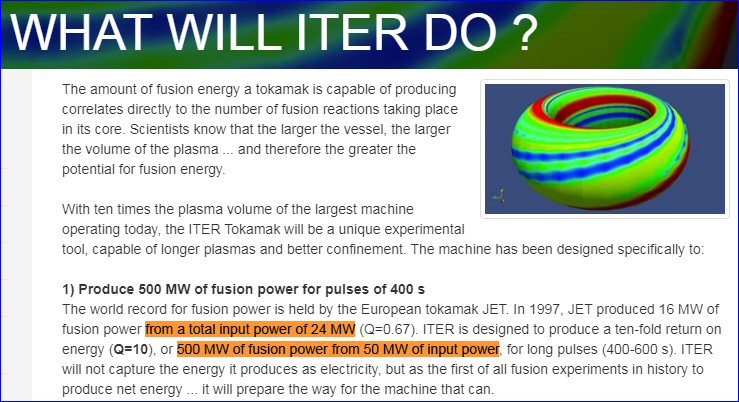

For the next two decades, the core message from the ITER organization regarding the objective of the project was communicated as shown in this screen capture below.

False claims made by the ITER organization, as published on its Web site, before Oct. 6, 2017 (Click here to see ITER organization’s correction soon after Oct. 5, 2017)

Here are the facts.

JET, the Joint European Torus fusion reactor, produced 16 megawatts of thermal power for a tenth of a second from 24 megawatts of heating power injected into the reaction chamber to heat the fuel. It also required additional power to operate — a total of 700 megawatts of electricity. This fact was publicly unknown before I contacted the U.K. Atomic Energy Authority in 2014.

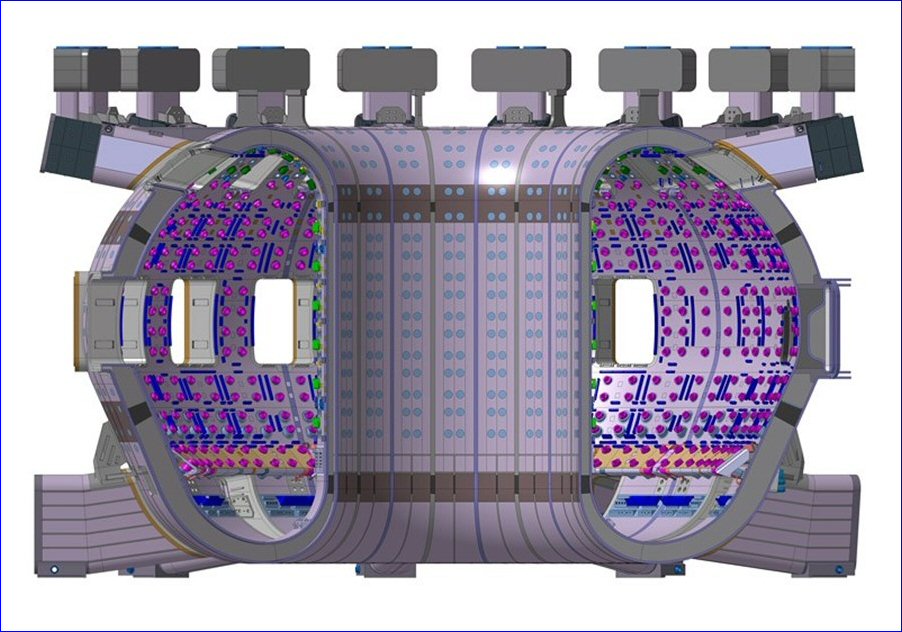

ITER is designed to produce fusion reactions with 500 megawatts of thermal power from 50 megawatts of heating power that will be injected into the reaction chamber to heat the fuel. This is its primary measurable scientific goal. (More technically, it is the kinetic energy of the particles that could be converted in heat.)

To accomplish this, the reactor will require 500 megawatts of electrical power to initiate the fusion reactions. The reactor will need 300 to 400 megawatts of electrical power throughout the experiment to produce the fusion reactions. If the reactor accomplishes its scientific goal, the overall reactor will not produce any net power or demonstrate a power gain. ITER is a zero-net-power reactor design. These facts were generally unknown and undisclosed to the public before I published this report on Oct. 6, 2017. Citations and scientific references are available on the New Energy Times ITER Power Research and Analysis Web page.

Why were the full input power requirements for these reactors not publicly disclosed by the fusion community? Why didn’t fusion scientists ensure that the public claims by their organizations were accurate and honest? Why did fusion scientists allow these discrepancies and misunderstandings to go on, decade after decade? The New Energy Times documentary film “ITER, The Grand Illusion: A Forensic Investigation of Power Claims” answers these questions.

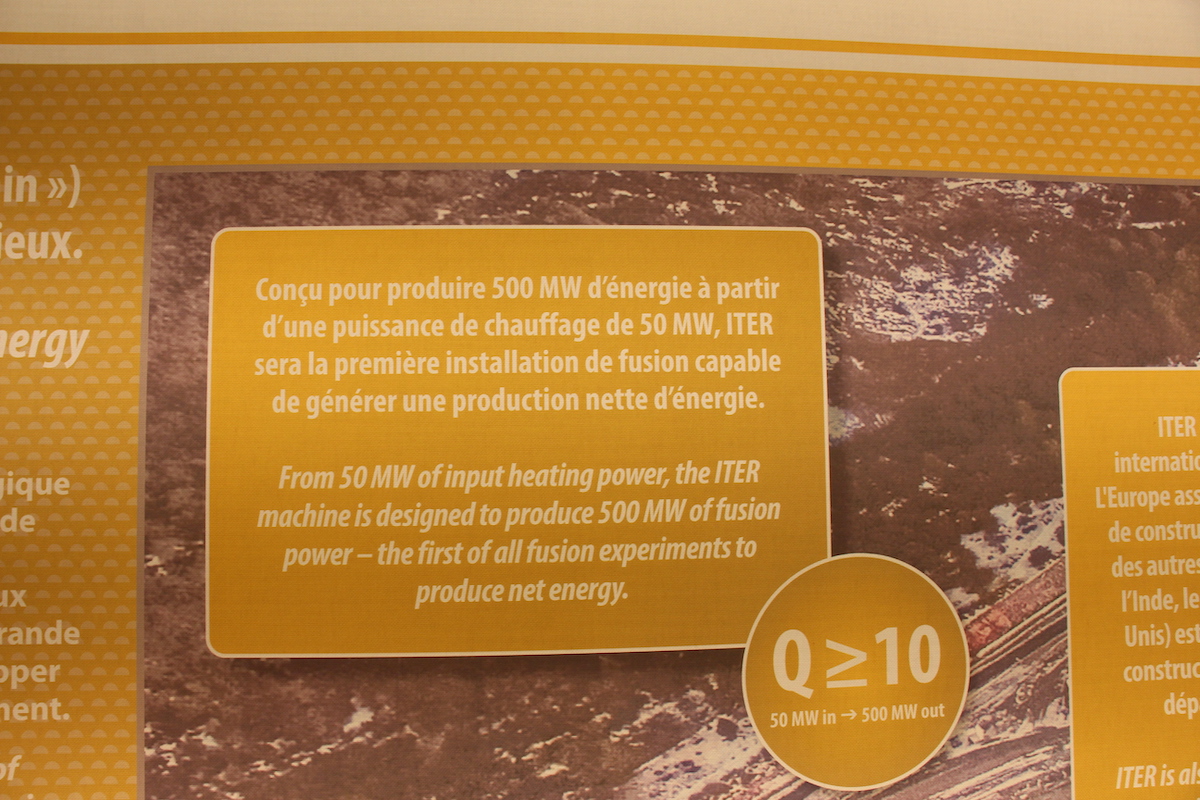

To this day, the ITER organization’s Web site continues to publish misleading statements about the primary measurable objective of the project, implying that the reactor itself is designed for a tenfold gain in power.

No Misunderstanding?

Journalist Grant Hill asked Coblentz earlier this year about the incorrect statements people have made about the ITER reactor power values. Coblentz said that he believes that most people understand that the ITER reactor is designed for a gain involving only the physics reactions, rather than the overall reactor.

“I don’t think there is a gigantic public deception or misconception,” Coblentz said.

For most of the past decade, prominent news organizations including The Guardian, Nature Magazine, Science Magazine and The New York Times, published significantly incorrect statements about the expected result of the ITER reactor. In most cases, the news organizations wrote that the overall reactor, not just the physics reactions, is designed for a tenfold power gain.

Coblentz told Hill that the ITER organization had made efforts to reach out to publications and journalists when it felt that journalists had misunderstood the power values. New Energy Times has compiled a list of more than 100 news articles that published the wrong power values. Gizmodo recently made a correction after one of our editors contacted the magazine in October. After New Energy Times contacted the National Law Review in 2020, the journal made a correction. After New Energy Times sent a comment to Nature magazine in 2017, the magazine made a correction. We are not aware of any other corrections to any of the 100-plus news articles that incorrectly stated the ITER design specification.

When Hill watched the New Energy Times documentary film, he saw that members of U.S. Congress, just like the journalists, had misunderstood the primary measurable objective of the ITER reactor.

During a congressional hearing on ITER in 2014, California Rep. Eric Swallwell said, “ITER is designed to produce at least 10 times the energy it consumes.” Texas Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson said that fusion scientists are “confident it is now possible to actually build a full-scale test reactor that produces far more energy than it uses.”

Coblentz told Hill that he was confident that the legislators correctly understood the goals of the project but intentionally made “simplifications” when they spoke during the hearing.

State of Confusion

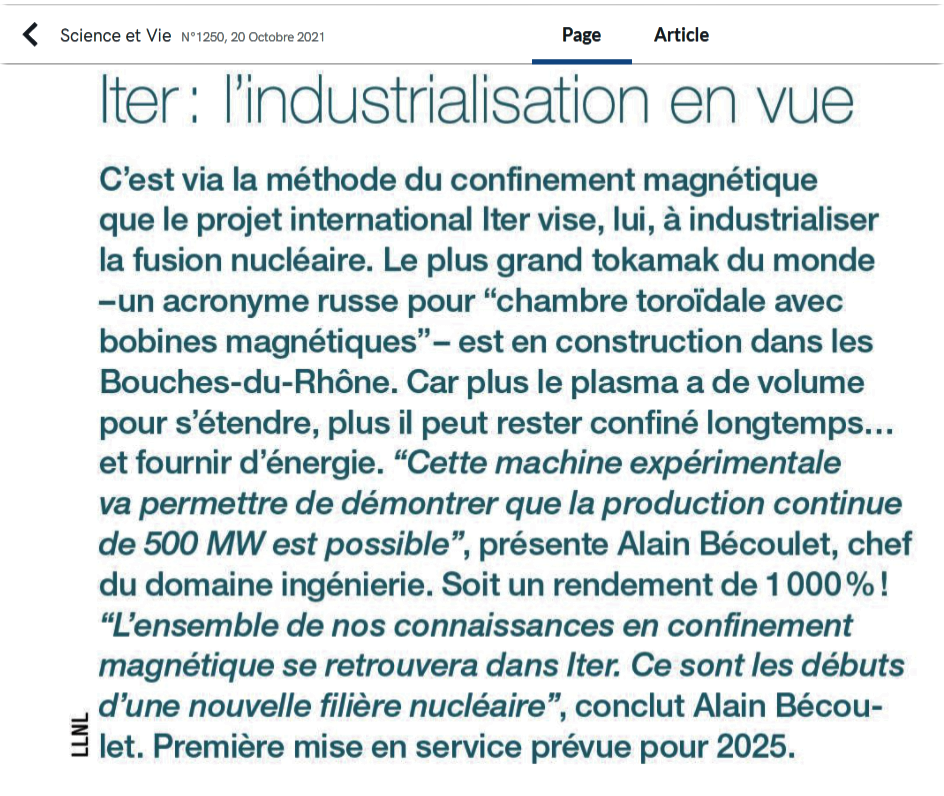

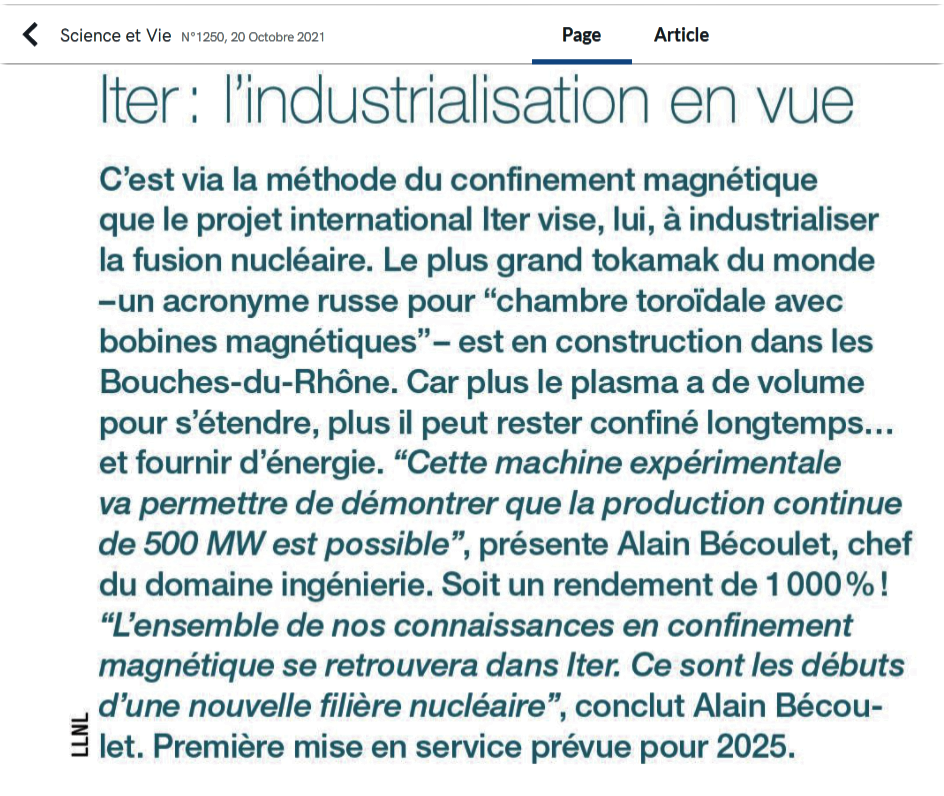

Despite the fact that the ITER organization informed Le Canard Enchainé last week that it is “obvious” that the overall ITER reactor will not produce power at a greater rate than it consumes power, subscribers of the popular French science magazine Science & Vie last week read a contradictory statement from Alain Bécoulet, the head of engineering at the ITER organization.

Bécoulet said the ITER machine is designed to demonstrate a tenfold power gain, producing a 500-megawatt output from a 50 megawatt input:

French: “Cette machine expérimentale va permettre de démontrer que la production continue de 500 MW est possible,” Alain Bécoulet said. Soit un rendement de 1000%!

English: “This experimental machine will enable the demonstration that continuous production of 500 MW is possible,” Alain Bécoulet said. Giving a gain of 1000%!

Alain Bécoulet

Contrary to Bécoulet’s claim, the machine, if it accomplishes its scientific goal, will end up with zero net power and zero gain. Contrary to Bécoulet’s claim, at the target output rate of 500 megawatts, the machine is not designed for continuous production of thermal power. Instead, it is designed to operate for about 500 seconds.

Incorrect information from senior ITER organization staff members is nothing new. A year ago, we reported that Tim Luce, the chief scientist for the ITER organization, was regularly telling journalists, “We plan to produce 500 megawatts with 50 megawatts of consumption.”

In the summer of 2017, we presented the discrepancies between the power facts and the power claims on the ITER organization’s Web site to David Campbell, the previous chief scientist for the organization. One month later, he submitted his resignation.

And just last week, hours after Le Canard Enchainé published the ITER organization’s confirmation that ITER is a zero-net-power reactor design, Bigot testified before the French Senate Committee on Economic Affairs, telling the senators that the overall ITER reactor is expected to demonstrate a gain of three to five times the power it will consume. (Click here for that news story.)

Understandably, members of the ITER organization may need some time to agree on a consistent set of messages.

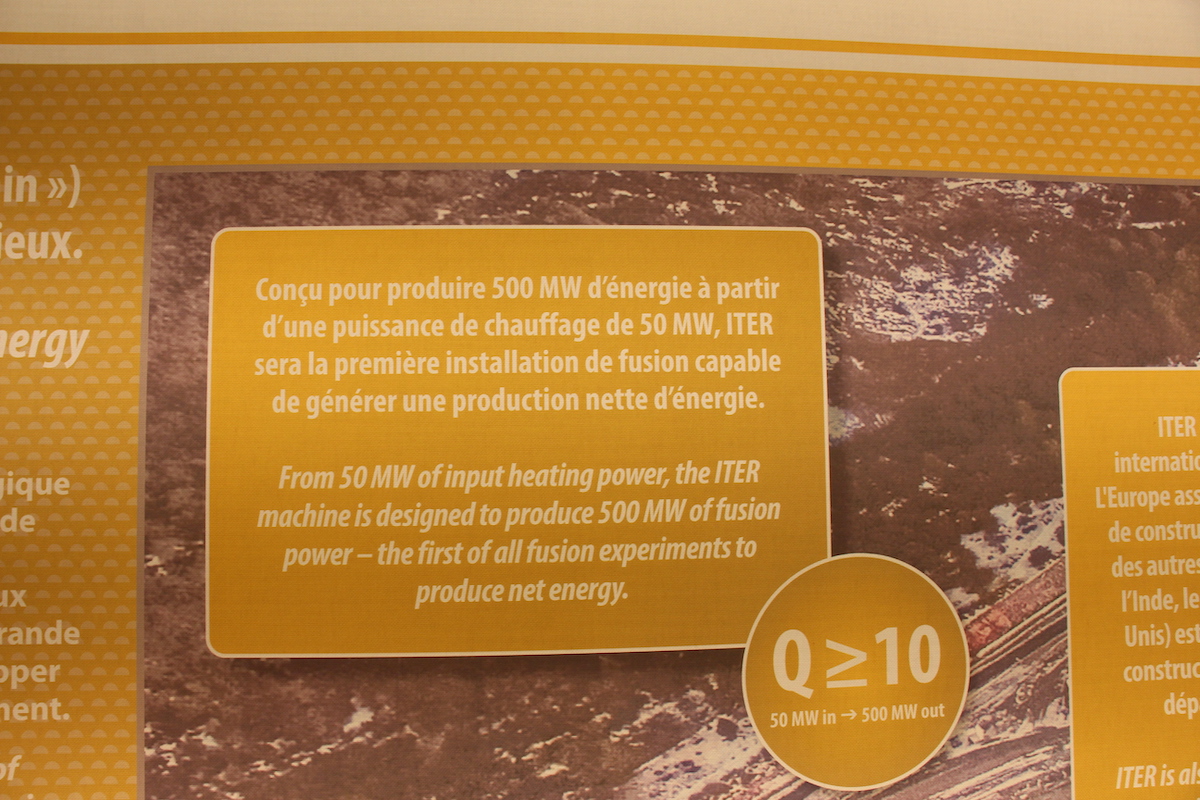

Wall display in the ITER headquarters building. (Photo: Celia Izoard)