#92 Commonwealth Fusion Cons Nature Magazine Journalist

Return to ITER Power Facts Main Page

By Steven B. Krivit

Nov. 21, 2021

Scientists working on the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Commonwealth Fusion Systems collaboration have misled members of the science news media again. The latest casualty is Philip Ball, an experienced U.K. science reporter.

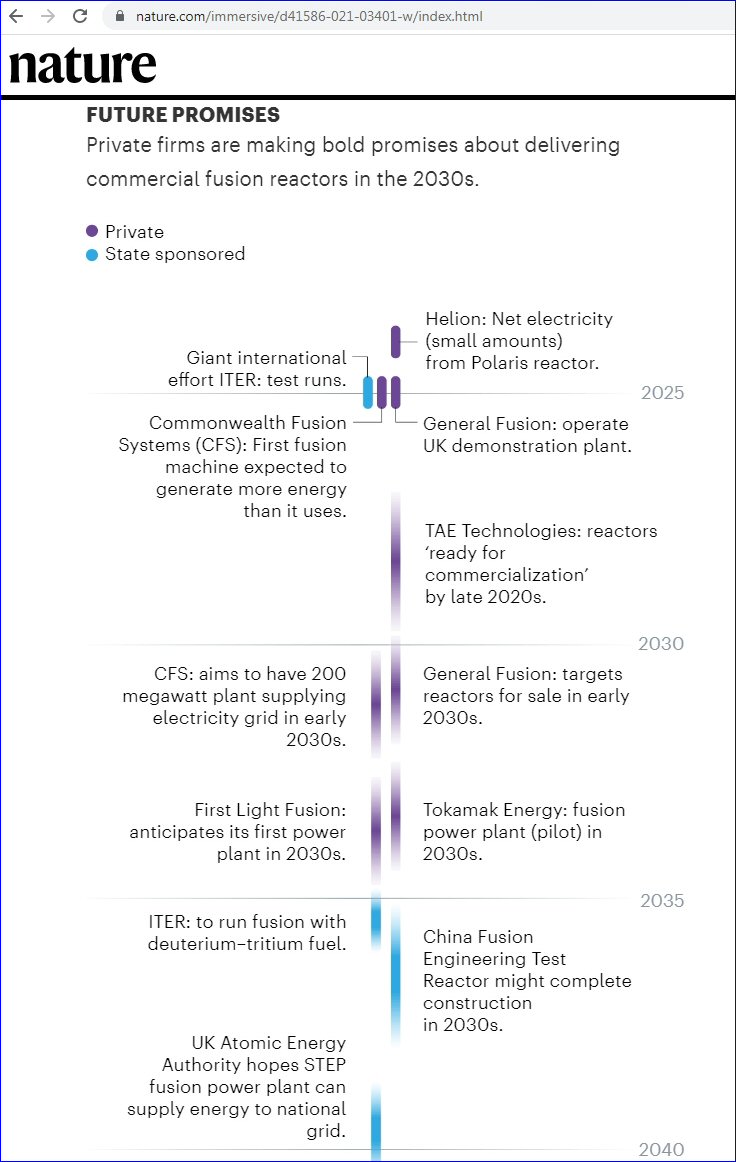

In a Nov. 17, 2021, news story, Ball wrote that scientists working with the MIT/CFS collaboration are planning to deliver the “first fusion machine expected to generate more energy than it uses” in 2025.

Actually, the MIT/CFS SPARC reactor is designed only to produce a fusion plasma that produces power at a higher rate than it consumes power. That measurement does not account for the input power required to operate the reactor. It’s the same trick that fusion promoters used to sell the idea of ITER, the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor.

The intended gain for the SPARC reactor applies to only the plasma, not the overall reactor, as MIT explained in a Sept. 8, 2021, press release written by David Chandler, who works in the MIT news office.

The MIT/CFS collaboration plans to “to build the world’s first fusion device that can create and confine a plasma that produces more energy than it consumes,” Chandler wrote. “That demonstration device, called SPARC, is targeted for completion in 2025.”

However, a few pages later, Chandler wrote that “the successful operation of SPARC will demonstrate that a full-scale commercial fusion power plant is practical.” SPARC, like ITER, is a zero-net-power reactor design. Chandler was confused or simply wrote what the MIT/CFS scientists told him to write.

Maria T. Zuber, a geophysicist who serves as the vice president for research at MIT, was also confused or misled by the fusion scientists. She told Chandler, “I now am genuinely optimistic that SPARC can achieve net positive energy.” She did not say in the press release that she was talking about only the plasma gain rather than the reactor gain. If she did mean to say that she was talking only about the plasma gain rather than the reactor gain, this was a serious omission — and one that went unnoticed by every person who reviewed that press release before it went out. Zuber has oversight responsibility for research misconduct at MIT and must be aware of the pitfalls of inaccurate science communication.

The fusion con has been going on for decades. Two years ago, fusion scientists told Ball that JET “set a world record for the highest ratio of energy out to energy in.”

“But that was still just two-thirds of the break-even point where the reactor isn’t consuming energy overall,” Ball wrote.

Actually, the 1997 JET experiment came to just one-one hundredth of the reactor break-even point. The input power rate for JET wasn’t 25 MW; it was 700 MW. It’s the same con: taking plasma gain values and creating the illusion that they are reactor gain values.

In the Nov. 17, 2021, Nature article, fusion scientists continued to mislead Ball and his colleagues about ITER. ITER will need 300 to 400 megawatts of electricity to operate, not just 50 megawatts, as Ball thought in 2019.

Ball is still having difficulty explaining ITER properly. Here’s what he wrote about ITER in the Nov. 17 Nature article:

[ITER has a] goal of continuously extracting 500 MW of power — comparable to the output of a modest coal-fired power plant — while putting 50 MW into the reactor. (These numbers refer only to the energy put directly into and drawn out of the plasma; they don’t factor in other processes such as maintenance needs or the inefficiencies of converting the fusion heat output into electricity.)

Fusion scientists told Ball that the remainder of the input power ITER will need is for “maintenance.” They lied. The 300 MW (minimum) is needed to operate ITER during the experiments, as plasma physicist Daniel Jassby explained to New Energy Times four years ago. Had Ball’s sources explained the projected power balance to him correctly, Ball would have understood that the equivalent net power output of ITER — if it is successful — will be about zero. That’s a bit less than the output of “a modest coal-fired power plant.”

The consequences — false hope given to the public, potential fraud affecting decision makers, and damage to the credibility of science journalism — are serious.

In Ball’s chart, his date for ITER’s “test runs” is already obsolete. Bernard Bigot, the director-general of the organization, announced in a press release on Sept. 17, 2021, that “first plasma in 2025 is no longer technically achievable.” We told our readers that news three months earlier.

Journalists jumping on the fusion cheerleader bandwagon would be wise to study the saga of fraudster Andrea Rossi, who, year after year, made extraordinary fusion claims. Each time one of his contraptions was debunked, he developed another contraption and made even bigger and bolder claims, always saying he would soon be delivering fusion power plants for sale. He delivered nothing but hot air and walked away with $11 million, thanks to the generosity of a dozen investors.

For journalists who would like to avoid the pitfalls of reporting on nuclear fusion, I strongly encourage watching my documentary film “ITER, The Grand Illusion: A Forensic Investigation of Power Claims.”