#58. False Fusion Claims by Ian Chapman, Head of U.K. Fusion

Return to ITER Power Facts Main Page

Related: Head of U.K. Nuclear Fusion Center Concedes Inaccuracies (Nov. 16, 2017)

By Steven B. Krivit

Nov. 7, 2020

Ian Chapman, Chief Executive of the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority

In this article, part of my ITER investigation series, I’ll be sharing with you some of the fusion reactor claims made by Ian Chapman. Chapman is the head of the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority and the Culham Center for Fusion Energy. He’s also the chairman of the Fusion Research Council of the International Atomic Energy Agency. Chapman made these claims — false claims — during a lecture in 2016 at the U.K.’s Royal Institution. Here’s a seven-second clip from the beginning of his lecture:

Chapman is one of the many fusion scientists who has contributed to the long-running misunderstanding about the rate of power older experimental fusion reactors have made and the rate of power the next major experimental fusion reactor is designed to make.

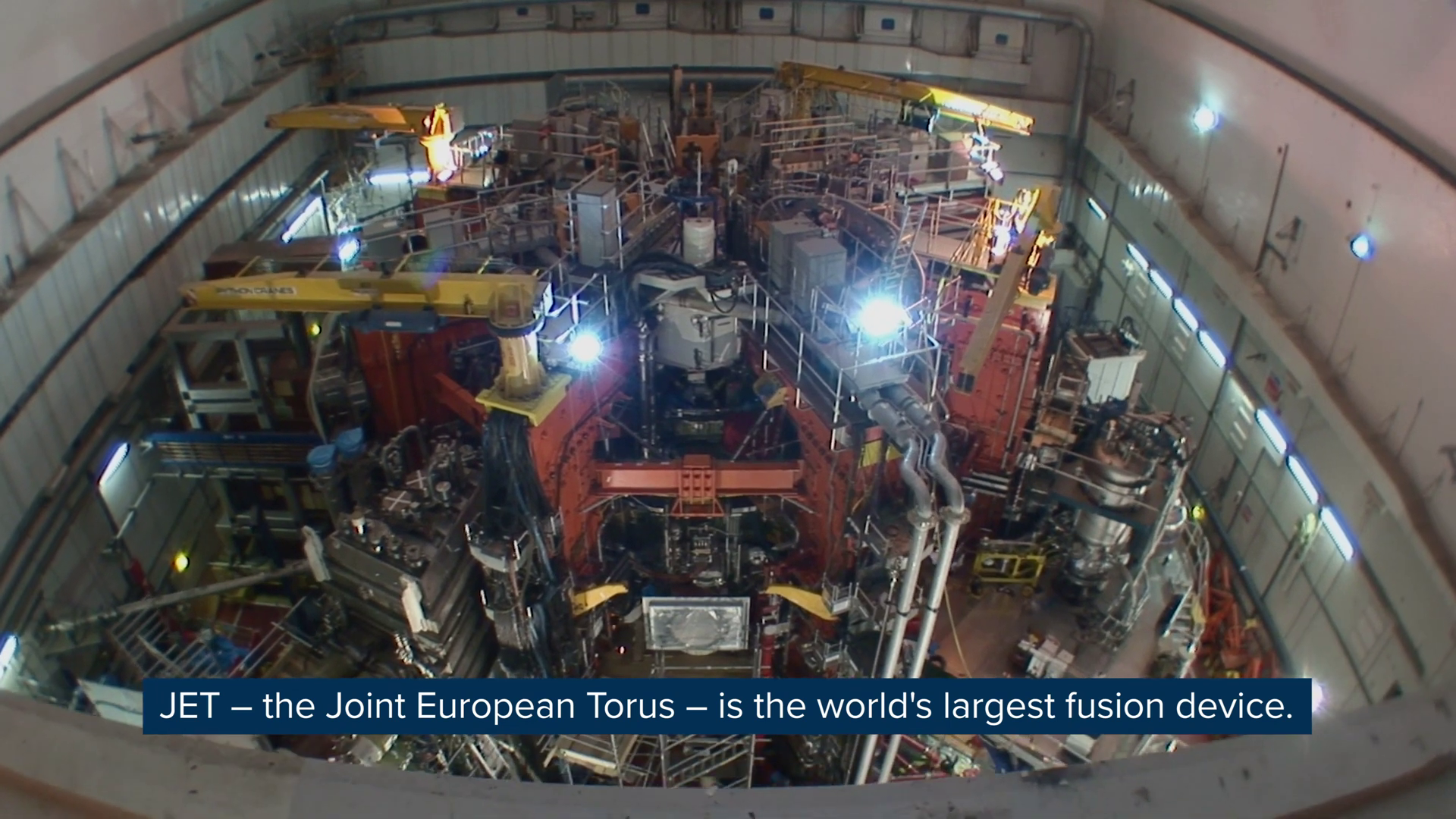

So far, the experimental fusion reactor that produced the highest power level was the Joint European Torus, JET, at Chapman’s Culham laboratory.

The next big fusion project is called the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, also known as ITER. It’s under construction now in southern France.

The Damage

Widespread false and exaggerated claims made by leaders in the fusion community have caused many people and institutions to convey the incorrect claims to a wide cross-section of the general public. Below, I’ve listed four of several hundred examples I’ve located. Each of these statements, through no fault of the authors, is fundamentally wrong:

- New York Times: “ITER will benefit from its larger size and will produce about 10 times more power than it consumes.”

- Science magazine: “ITER aims to produce 500 megawatts of power, 10 times the amount needed to keep it running.”

- Nature magazine: “ITER is predicted to produce about 500 megawatts of electricity.”

- Columbia University: “Overall, ITER aims to produce 500 MW of power from a 50 MW investment.”

In fact, the overall ITER reactor is designed to produce 500 megawatts of thermal power from an investment of 300 megawatts of electrical power. With conversion efficiencies, the net output of ITER should be around zero. From a practical perspective, that’s bad news. But from a scientific perspective, if it made only as much power as it consumed, it would be good news. I’ll explain why in a moment.

JET

The JET reactor holds title to the world record, in terms of power level achieved, from a fusion reactor experiment. It took place on Oct. 31, 1997. This is the graph that shows the result for that experiment.

JET 1997 Experiments

This graph actually shows three experiments, but we’re going to look only at the experiment shown by the blue line. The vertical axis is the rate of thermal power emitted by the fusion reaction. The horizontal axis is time, measured in seconds. So in this experiment, the fusion reaction lasted for about 2 seconds. Here’s how Chapman explained it:

“We produced 16 megawatts here in JET. Sixteen megawatts is a reasonable amount of energy. It’s not commercial. You certainly wouldn’t ever put that onto the grid, but it’s a reasonable amount of energy. The big problem is that that 16 megawatts was generated having put 25 megawatts into the machine. So nobody’s going to pay you to do that.”

Not Funny

Chapman got his expected laughter from the audience, but what wasn’t so funny is that JET didn’t consume electricity at a rate of 25 megawatts. Rather, it consumed electrical power at a rate of 700 megawatts to get the 16 megawatts of thermal power from fusion.

So of course they couldn’t connect JET to the grid. It lost 99 percent of the power flowing into it. How do I know JET’s input power rate was 700 megawatts, rather than Chapman’s value of 25 megawatts? Two years before Chapman took the helm at Culham, I had asked Nick Holloway. He’s the spokesman for the Culham center. I sent Holloway an e-mail, and two days later, he got back to me with the information. Holloway was straightforward with me about it even though nobody had publicly disclosed that value before.

So what was Chapman talking about when he said 25 megawatts? Did he make up that number? No, it’s a real number, but it means something else.

Chapman was talking about the rate of thermal power that was injected into the fuel chamber. The input power rate of 25 megawatts had nothing to do with the overall power rate that the reactor used and needed to operate.

Chapman had swapped out the 700-megawatt value for the 25-megawatt value without giving any indication to his audience that he had done so or telling his audience what the 25-megawatt value was really supposed to mean.

ITER

With the false foundation he established using JET, Chapman moved on in his lecture and began talking about the ITER reactor, doing the same switch with the power values and omitting most of the required input power:

“In the next-step device, we’ll put in 50 and get out 500. And that’s the aim of the machine.”

As you probably figured out, the 50-megawatt value Chapman was talking about is not the input power rate that will be needed for the overall ITER reactor. The 50 megawatt value is only the rate of thermal power that is supposed to be injected into the fuel chamber.

To operate the entire reactor, ITER will need to consume electrical power at a rate of 400 megawatts to start up – for the first 20 seconds. Then, for the rest of the 500-second experiment, the reactor is supposed to consume electrical power at a rate of about 300 megawatts continuously.

Omission

Chapman was doing the same thing that leaders of the ITER project have been doing for years: exaggerating the projected output power rate of the overall reactor by omitting the majority of the input power rate the reactor will require. Later in Chapman’s talk, he repeated the false claim about ITER:

“Ultimately, the aim of this device is that, as I say, we’ll produce about 10 times more energy out as we put in. We’ll put 50 megawatts in to heat the fuel in the first place. Once the fuel is hot and the fusion is happening, it will produce about 500 megawatts out.”

Chapman knew that the 50-megawatt value applies only to the rate of power used to heat the fuel. Nevertheless, he consistently told his audience that the entire device would need a rate of only 50 megawatts of input power and that the entire device would produce 10 times more power than it is designed to produce:

“ITER’s about 500 megawatts. Now 500 megawatts is not that much; in fact, it’s very small in terms of reactors. If you look at a fission reactor or a coal plant, these are usually one or two gigawatts.”

The expected output, according to the design, is even smaller than Chapman implied. If a reactor with ITER’s parameters was configured to convert its thermal power to electrical power, there wouldn’t be enough power left over for a single light bulb.

Consistently False

This is not the only place that Chapman has made false fusion claims. He did so in an article published by the U.K. Sunday Times in 2017.

The next year, editors of The Guardian wrote an editorial to encourage public support and public funding for fusion research in the U.K. The editors called JET’s record-setting experiment the “gold standard” in fusion research. The editors wrote that JET produced 16 MW of output power from only 25 MW of input power, rather than 700 megawatts of input power.

I wrote to the editors of The Guardian and told them that their local fusion experts had given them wrong information. They didn’t write back, let alone publish a correction.

Chapman is one of many leaders in the nuclear fusion field who has, when speaking to public audiences about JET or ITER, omitted most of the input power, thereby grossly exaggerating claims of net output from fusion reactors.