#54. Omitting the ITER Input Power – Cardozo’s Role

Niek Lopes Cardozo

Return to ITER Power Facts Main Page

By Steven B. Krivit

Oct. 17, 2020

Promoters of the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, ITER, have a long history of telling the public how much output power they should expect from this experimental reactor. At the same time, they have a long history of omitting the required input power. Perpetual-motion scams do the same thing, only with mechanical tricks.

Earlier this year, I contacted Niek Lopes Cardozo, one of the fusion scientists who had helped promote ITER. Cardozo is a professor of science and the technology of nuclear fusion in the Applied Physics Department of Eindhoven University of Technology, and he is the interim chair of the science domain of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research.

Cardozo is the former leader of the Dutch fusion research programme (2001-2009) and served on top-level European fusion governance committees, and he was the vice-chair of the governing board of the ITER European domestic agency known as Fusion for Energy, which was involved in false power claims about ITER. Cardozo was a co-founder of FuseNet, a European educational organization that teaches students about fusion. For at least eight years, FuseNet had published a fundamentally false claim about the promised ITER power production.

ITER is not designed to produce electricity; nor is it designed to produce overall net power. It is designed specifically for a purely scientific outcome: a fusion plasma that produces thermal power at a rate 10 times greater than the rate of thermal power injected into the plasma. This goal, if achieved, will translate to a net-zero output for the overall reactor. Representatives of the fusion community who have spoken about ITER publicly have told the public for three decades that the overall reactor was designed to produce significant net power, that the overall reactor was designed to produce power at a rate 10 times greater than the power the reactor would consume. That’s not what its designed for. If it works, it will produce thermal power at the same rate as it consumes the equivalent rate of electrical power.

In his own communications, Cardozo contributed to many false claims about ITER. He was willing to respond to my e-mails — up to a point.

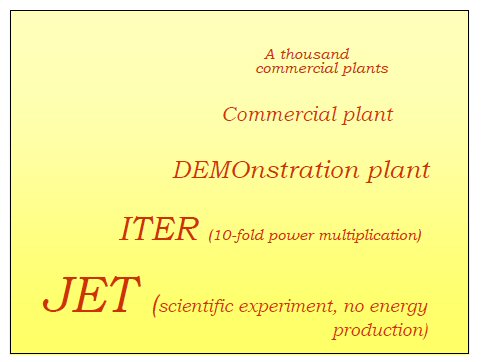

In his presentation (date unknown) “Fusion: the 7 scientific challenges between us and clean power,” Cardozo displayed two slides saying that ITER is designed for a “tenfold power multiplication.” His slides gave no indication that the power multiplication applied only to the plasma rather than to the overall reactor, thus leading his audience to believe the false idea that the overall ITER reactor was designed for a tenfold power multiplication.

When I asked him to explain this apparent misrepresentation, he said that, when he introduces the “10-fold power multiplication,” he always explains to his audience that he really means “that the fusion power is 10 times the power needed to sustain the plasma.”

Changing Measurement Scales

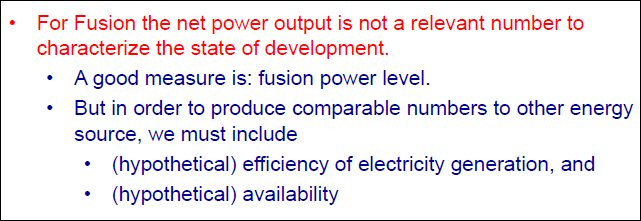

I found a 2015 slide presentation he had given called “Why We Have Solar Panels But Not Yet Fusion Power.” Cardozo wrote that the net power output of a fusion reactor is not a relevant measure of fusion progress.

It was a peculiar statement because nearly every news story about nuclear fusion for the last 50 years has described the penultimate goal of fusion research as a fusion reactor that produces net power output. On the other hand, a fusion reactor that produces no net power has scientific value but, on a practical level, is useless.

When Cardozo wrote “fusion power level,” he was using a phrase that fusion scientists commonly use – a phrase with a double meaning. Cardozo was not talking about the practical meaning, which is the potentially usable rate of power produced by a fusion power plant. He was talking only about the scientific meaning: the rate of power associated with particles produced by the fusion reactions, which does not account for any of the input power.

But the public doesn’t care about the kinetic energy of fusion particles; for 70 years, the public has been promised and has been waiting for a fusion reactor that creates more energy than it consumes. Cardozo’s assertion that net reactor output power was “not a relevant number” was inconsistent with the real purpose of fusion research, so I asked him what he had in mind. Here’s what he told me:

Fusion has the peculiar property that it has to reach ignition, which in the case of magnetic fusion, basically requires upscaling. For a long time, the input power is simply [going to be] much larger than the fusion power; then [we will] get to a machine size where the two cross, and from there on, [we get to] the net power production size.

A note about ignition: All magnetic fusion reactors require heat to be injected into the reaction chamber to create nuclear fusion reactions. However, fusion scientists believe that, when they eventually build a reactor that has all the right parameters, the fusion reactions inside the reactor will create so much heat that no external heating power will be required. They call this “ignition.”

In his explanation, Cardozo was saying that net reactor output power was irrelevant only because, for the time being, there is no fusion reactor capable of positive net reactor output power. Once a fusion reactor reaches the ignition level and no external heating power is required, Cardozo expected a fusion reactor to have net positive reactor output power. In that case, according to Cardozo, net reactor output power would be relevant. Before ignition, Cardozo expects that net reactor output power will remain negative. After ignition, he expects that net reactor output power will be positive. More simply, Cardozo doesn’t want to use the net reactor output power value now because it gives a negative number.

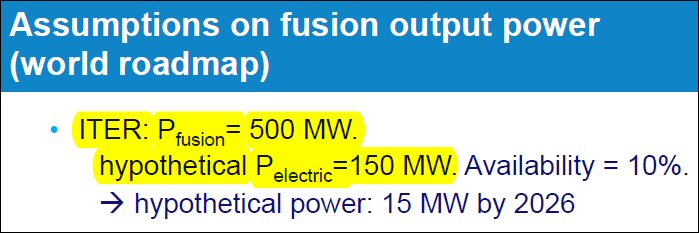

In the same presentation, Cardozo said that ITER is supposed to produce enough thermal power that, if converted to electricity at a 30% rate of efficiency, would yield 150 megawatts of electric power.

Cardozo’s claim that ITER would hypothetically be able to produce electrical power at the rate of 150 megawatts seemed wrong because Cardozo’s value didn’t account for the 300-megawatt rate of electricity the reactor is expected to consume. I asked him to explain the omission of the required input power, but he did not respond directly to my question. Instead, he told me that in recent years he has been critical about the prospects of fusion as a practical source of energy in a relevant and useful time frame, and he directed me to a journal article he wrote last year.

Volte Face

Cardozo’s article is a radical shift from his earlier outlook. His previous public comments about fusion, like those of so many other fusion scientists, were filled with the same imaginary projections that fusion scientists have been talking about for half a century. His new outlook was based on sobering, thoughtful analysis. He asked, and answered the question, what if ITER works as planned? Then what? Based on what we know of nuclear engineering, what would it take to develop fusion into an energy technology that makes any difference in the world energy mix? How long would it take?

Cardozo concludes that “within the mainstream

In his estimation, the first-generation fusion power plants, optimistically offered to the market in the 2070 timeframe, likely will provide an average electric power comparable to what wind power provided in the year 2000. Moreover, he wrote, such fusion power plants would require an upfront investment of hundreds of billions of Euros. Cardozo asked: Who would pay for that? And why? Cardozo wrote that other energy technologies have already provided proof of technical viability at investment levels orders of magnitude lower.

Leaving the Past in the Past

Despite his turnabout, a large part of my work recently has been an attempt to explain the past and how we got where we are now, or at least where we were three years ago, when almost every major fusion organization was publishing false or misleading claims about ITER. I wanted to know whether Cardozo could and would explain his role as a contributor to the widespread false understandings about ITER. I sent him several examples:

- Oct. 20, 2006, News Report in Technisch Weekblad, “ITER Has To Keep All Promises”

In this news report, after speaking with Cardozo, the reporter wrote that “ITER promises to be the first fusion reactor to deliver more power than it needs to run: 500 MW for ten minutes, ten times more than what is put into it.” This was false. If ITER works, it will only be the first fusion reactor to deliver the same amount of power that it consumes.

– - September 2010, Cardozo’s Abstract for the 9th Liege Conference on Materials for Advanced Power Engineering

As Cardozo had written in a slide presentation, his abstract for this meeting said that ITER “will demonstrate 10-fold power multiplication at the 500 MW level.” This statement gave the clear but false impression the expected power gain is for the overall reactor and not limited to only the plasma.

– - April 20, 2009, Press Release About Cardozo’s Chair Appointment

This press release, which relied on Cardozo as the expert, said the ITER “installation will generate 500 MW of power from nuclear fusion, ten times more than is necessary to operate the reactor.”

– - Eindhoven University of Technology Web Site

The Master Science and Technology of Nuclear Fusion Web page at Cardozo’s university says, “ITER will demonstrate 10-fold power multiplication at the 500 MW level.” The press release mentioned above said that Cardozo would be setting up this nuclear fusion master’s program.

– - FuseNet Association

Cardozo was the founding chair of the board, from 2010 to 2014. From at least 2011 to 2019, he and his peers told students on the association’s ITER page that “the fusion reactor itself has been designed to produce 500 MW of output power, or ten times the amount of power put in.”

Silence

I didn’t know whether, like some other fusion scientists, Cardozo had believed that ITER would need only 50 megawatts of power to operate. I didn’t know whether he had been given wrong information by his peers or whether he made a mistake.

I sent him another letter, copied to Robert-Jan Smits, the president of Eindhoven University of Technology, and asked Cardozo for an explanation.

Cardozo did not reply.