50. Omitting the ITER Input Power – Martin Greenwald’s Role

Martin Greenwald

Return to ITER Power Facts Main Page

By Steven B. Krivit

Sept. 29, 2020

Promoters of the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, ITER, have had a long history of telling the public how much thermal output power they should expect from this experimental reactor. At the same time, they have had a long history of omitting the required input power. Perpetual-motion scams do the same thing, only with mechanical tricks.

More than 200 examples show that the ITER promoters fooled staff members of industry, government agencies, and energy organizations; editors for English, French, and Italian Wikipedia pages; scores of journalists, including those with the New York Times, Science magazine, Nature magazine, and The Guardian; university students, including those at Stanford and Princeton; and staff writers for the European Commission, European Parliament, and the White House.

Earlier this year, I spoke with Martin Greenwald, one of the fusion scientists who had helped promote ITER. Greenwald is the deputy director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Plasma Science and Fusion Center.

ITER is not designed to produce electricity; nor is it designed to produce overall net power. It is designed specifically for a purely scientific outcome: a fusion plasma that produces thermal power at a rate 10 times greater than the rate of thermal power injected into the plasma. This goal, if achieved, translates to a net-zero output for the overall reactor. Representatives of the fusion community who have spoken about ITER publicly have told the public for three decades that the overall reactor was designed to produce significant net power, that the overall reactor was designed to produce power at a rate 10 times greater than the power the reactor would consume. That’s not what its designed for. If it works, it will produce thermal power at the same rate as it consumes the equivalent rate of electrical power.

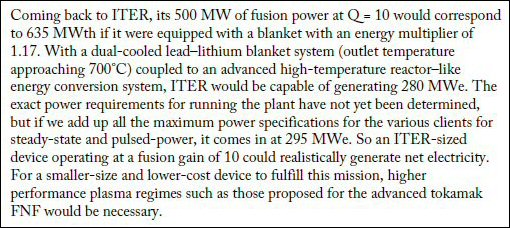

In 2012, the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) published a report called “Program on Technology Innovation: Assessment of Fusion Energy Options for Commercial Electricity Production.” Greenwald was one of the fusion experts consulted. The report makes the following claims about ITER:

I first asked Greenwald how he derived his gross thermal output value: 635 MWth. It was close but didn’t match my value of 686 MW. He explained his calculation and taught me something new: A significant portion of the thermal energy of the fusion-produced alpha particles, the 100 MW of internal heating, is expected to be recovered by the divertor.

In the next part of our discussion, he gave me a more detailed breakdown of the gross thermal output value, which he recalculated as 618 MW instead of 635 MW. From the 618 number, he used a high thermal-to-electric conversion rate of 0.454 and ended up with 280 MW gross electric output.

With a mutual agreement about those numbers, I moved on and asked him how he concluded that the device could “realistically generate net electricity” considering the steady-state input power requirement of 300 MW of electricity.

The 300 MW input power value was new to him. He didn’t know where that value came from. He didn’t seem to have a basic understanding of the reactor power drains. I showed him how the 300 MW value was calculated and showed him my sources. Then he stopped responding to my e-mails. Here’s a record of those two messages.

Around the same time, I began a conversation with ITER scientist Gregory DeTemmerman to crosscheck the new information Greenwald had given me about thermal recovery from the divertor. I also cross-checked the divertor thermal recovery with Hartmut Zohm, a fusion scientist at the Max-Planck-Institute of Plasma Physics. After I obtained a consensus, I updated my “ITER Reactor Power Values — Bar Chart” and, in a group e-mail, sent it to the sources who contributed to the information in the chart.

In one of the messages in that discussion thread, I reminded Greenwald that he had not answered my question about how ITER was supposed to “realistically generate net electricity.” I asked him whether I was missing something or whether his report contained an inaccuracy. Here is his response:

1. During a pulse, the ITER facility as a whole will produce substantial net power. 2. That magnitude of excess power, if it were converted from thermal to electrical power, would very roughly balance the input.

His point No. 1 was not valid because it was an apples-to-oranges comparison: comparing electric power in to thermal power out. Without directly admitting it, his point No. 2 confirmed that he and his colleagues had made a false claim. They had claimed that ITER, if coupled to an energy conversion system, would be capable of generating 280 megawatts of electricity. They had omitted the expected input power required to operate the reactor. Had they included the input power, their text would have read “ITER, if coupled to an energy conversion system, would be capable of generating 0 megawatts of electricity.”