The World’s First Successful Alchemist (It Wasn’t Rutherford)

May 14, 2019 — By Steven B. Krivit —

First in a Series of Articles on the Rutherford Nitrogen-to-Oxygen Transmutation Myth

The Myth

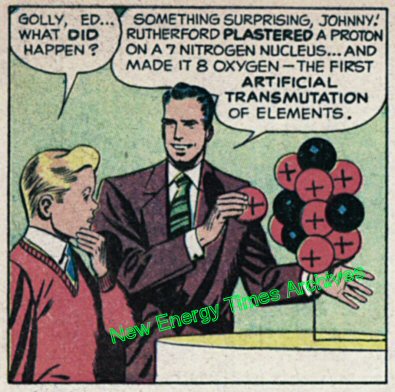

For at least 70 years, the near-consensus of the scientific community about the person who discovered the first confirmed artificial nuclear transmutation has been wrong. An illustrated example of the myth appears in a frame of a 1948 comic book produced by the General Electric Co. The book, Adventures Inside the Atom, sponsored by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, was propaganda intended to promote the new age of atomic energy.

The book begins in ancient Greece with Aristotle and the concept of the atom. Eventually, the story arrives at the University of Cambridge, in the laboratory of Ernest Rutherford.

Myth of the first artificial nuclear transmutation, 1948, General Electric Co.

According to the myth, Rutherford bombarded nitrogen nuclei with energetic alpha particles, and in doing so, became the world’s first successful alchemist, changing the element nitrogen into the element oxygen.

He did no such thing. Instead, Patrick Blackett, a research fellow working in Rutherford’s lab in Cambridge, performed the experiment, obtained the data, analyzed it correctly, and published it in a journal article in 1925. The full details, not only of this history but also of how I learned the facts, are in my 2016 book Lost History. At the time, I had located only two historians who had published the correct version of this history: Milorad Mladjenovic and Peter Galison. I later found that Mary Jo Nye and Roger Stuewer also correctly described the history. I contacted Nye and Galison and neither was aware of the extent of the incorrect version of this history.

Here is how the actual scientific discovery took place.

The Facts

In 1919, Rutherford published a series of four papers titled “Collisions of Alpha Particles With Light Atoms,” parts I, II, III and IV, published in the Philosophical Magazine. [2-5]

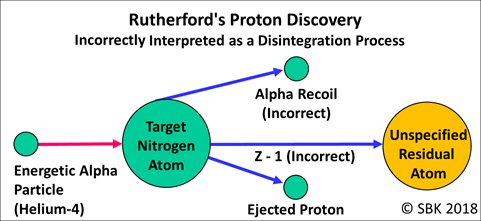

With the benefit of hindsight, we can certainly understand that Rutherford’s experiment would have caused the transmutation of nitrogen to oxygen and that the fundamental reaction mechanism was an integration process; the capture of the impinging alpha particle by the target nitrogen nucleus. However, as his papers show, Rutherford did not obtain or observe evidence for these two concepts. He therefore, of course, made no such claims in his 1919 papers. Nor was that his objective.

Rutherford’s intent, as he wrote to his colleague Niels Bohr in 1917, was to better understand “the character and distribution of forces near the nucleus” and to shatter the nucleus to better understand its structure and constituent particles. He also wanted to ascertain the origin of what he then called the swift hydrogen atom, or the positive electron. He correctly intuited that this particle was “a unit of which all atoms are composed.”[6]

Ernest Marsden, a research assistant in Rutherford’s laboratory, had preceded Rutherford in similar experiments. Marsden, however, had thought that in those experiments, the origin of this swift hydrogen atom was the radioactive source being used for its emission of energetic alpha particles. Rutherford definitively showed that this swift hydrogen atom was coming not from the radioactive source but from the interaction with the nitrogen particle and that it was indeed a fundamental particle which, the following year, he named the proton.

These were notable accomplishments, but that is the limit of Rutherford’s 1919 discovery. Rutherford did not discuss in his four papers the nature of the residual nucleus after impact by the alpha particle and he incorrectly presumed that the impinging alpha particle knocked out (what we now know as) the proton in a disintegration process. The research and discoveries of Patrick Blackett, another recent graduate and research fellow working in Rutherford’s lab, shed light on these matters.

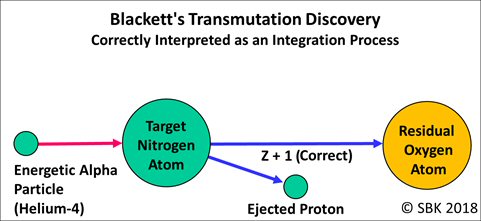

From 1921 to 1924, Blackett used the Wilson cloud chamber to take 23,000 photographs of 400,000 particle tracks. Among these, eight telltale sets of tracks revealed to Blackett that the alpha particle bombarding the nitrogen nucleus was, in fact, captured by the nitrogen nucleus which then nearly immediately ejected a proton, leaving behind the residual nucleus of a larger atom, that of oxygen. This also revealed that the fundamental nuclear process was one of integration, not disintegration. Blackett published this data and his conclusion in his 1925 paper. [7]

The Correction

In January 2017, after my book published, I began an outreach program to inform the scientific and academic communities in an effort to correct the recorded history. I selected five prominent organizations whose Web pages with the error ranked high in search results.

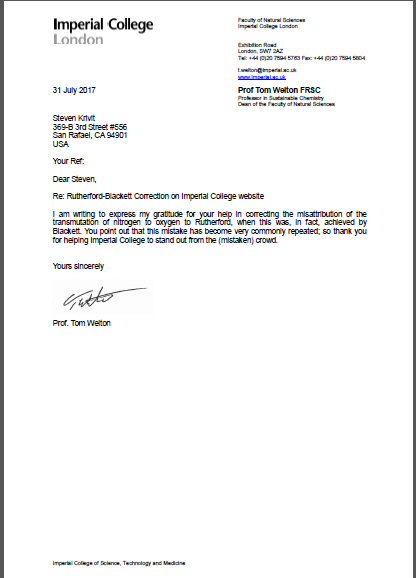

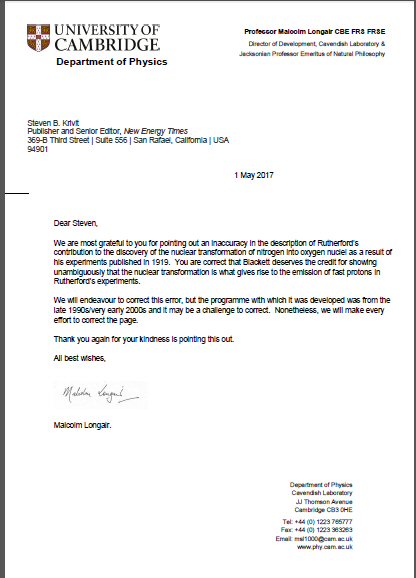

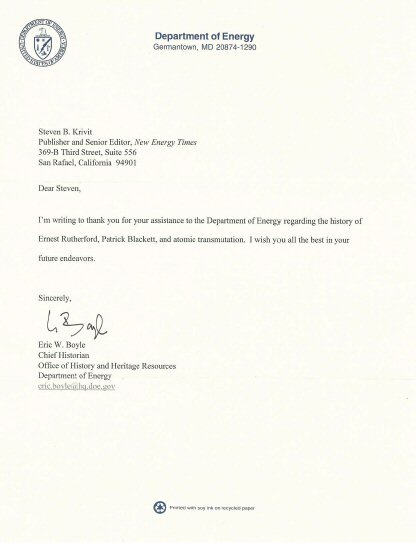

Sixteen months later, and after the exchange of several hundred e-mails, the first group had made almost all the corrections. This group included scholars at the American Institute of Physics, Cambridge University, Imperial College, the Nobel Foundation, and the U.S. Department of Energy. It is evident from my discussions with the chief historians at the AIP and DOE that they performed extremely comprehensive independent reviews of the history. The full list of original and corrected pages is here. Some of the acknowledgment letters are shown below.

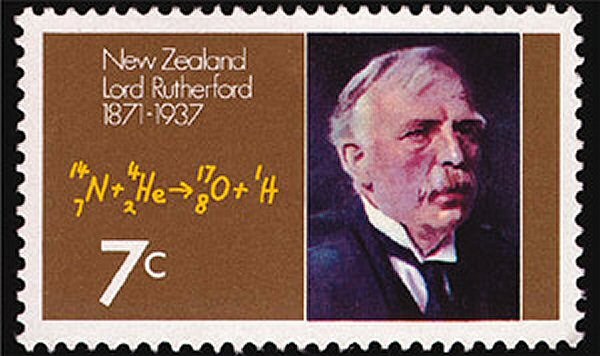

New Zealand postage stamp with the chemical reaction discovered by Patrick Blackett

1. Krivit, Steven B. (2016) Lost History: Explorations in Nuclear Research, Vol. 3, Pacific Oaks Press

2. Rutherford, Ernest (June 1919) “Collisions of Alpha Particles With Light Atoms: I. Hydrogen,” Philosophical Magazine, Series 6, 37, p. 537-61

3. Rutherford, Ernest (June 1919) “Collisions of Alpha Particles With Light Atoms: II. Velocity of the Hydrogen Atom,” Philosophical Magazine, Series 6, 37, p. 562-71

4. Rutherford, Ernest (June 1919) “Collisions of Alpha Particles With Light Atoms: III. Nitrogen and Oxygen Atoms,” Philosophical Magazine, Series 6, 37, p. 571-80

5. Rutherford, Ernest (June 1919) “Collisions of Alpha Particles With Light Atoms: IV. An Anomalous Effect in Nitrogen,” Philosophical Magazine, Series 6, 37, p. 581-87

6. Trenn, Thaddeus (March 1974) “The Justification of Transmutation: Speculations of Ramsay and Experiments of Rutherford,” Ambix, 21(1), p. 53-77

7. Blackett, Patrick Maynard Stewart (Feb. 2, 1925) “The Ejection of Protons From Nitrogen Nuclei, Photographed by the Wilson Method,” Journal of the Chemical Society Transactions. Series A, 107(742), p. 349-60

Next Article: Rutherford’s Reluctant Role in Nuclear Transmutation