20. Steven Cowley’s Role in the Misleading JET and ITER Fusion Claims

June 12, 2018 — By Steven B. Krivit —

Sir Steven Cowley (Photo: Royal Society)

For more than a decade, Steven Cowley, a prominent U.K. scientist, has withheld material information about the performance of the Joint European Torus (JET) fusion reactor. He has also promulgated misleading information about the JET result to the general public, specifically about the power input and net power output of the reactor.

Cowley was appointed the president of Corpus Christi College in October 2016. He is the former head of the Culham Centre for Fusion Energy in the U.K. and the chief executive officer of the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority. He was a member of the U.K. Prime Minister’s Council of Science and Technology from 2011 to 2017. As of July 1, 2018, he will become the 10th director of the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory in New Jersey. On June 9, Cowley received a knighthood from Queen Elizabeth “for services to science and the development of nuclear fusion.”

On April 2, 2018, New Energy Times sent a letter to Cowley, pointing out one set of his misleading statements about JET and asking whether he would publish a clarification. Cowley did not respond. The purpose of this report, therefore, is to provide the public with the facts. Cowley’s actions are not unique in the fusion research field, nor are they new.

Forty Years Ago

For example, in 1978, Anne Davies, a fusion physicist working for the U.S. Department of Energy, spoke with journalist Edward Edelson, writing for Popular Science. Davies told Edelson that the forthcoming fusion reactor at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory “will not just achieve a power breakeven but will be a net power producer, in terms of heat.”

In fact, that reactor was never designed to make as much power as it consumed. It produced, in heat, only 1 percent of the 950 million Watts of electrical power it consumed. When I interviewed Davies earlier this year, she said Edelson had misquoted her.

Referring to the public confusion about fusion claims, she also said that the people who are very knowledgeable about fusion “can easily let slip by some of the details that are important for people to understand.” Important details slipped by again when Davies spoke with a journalist in 1992, again in 2003, and again to members of Congress in 1993. During 1993 congressional hearings, several other fusion representatives, including Stewart C. Prager, a former director of the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, also provided misleading information during their testimony. (PDF)

This Year

On March 6, 2018, two other prominent fusion scientists again provided misleading information during a congressional hearing. The scientists were James W. Van Dam, the acting associate director of the Department of Energy’s Office of Fusion Energy Sciences, and Bernard Bigot, the director-general of the organization building the $22 billion International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, known as ITER.

At the time of the March 6, 2018, congressional hearings, the ITER organization’s Web site said that the most successful fusion experiment in history, which took place at the U.K. Joint European Torus (JET) reactor on Oct. 31, 1997, had produced 16 MW of output power from a “total input power of 24 MW.” In fact, the JET reactor required a total input power of 700 MW of electricity. Bigot repeated the same misleading claim when he testified before Congress.

Hidden Power Values

In the summer of 2017, Cowley and I exchanged a few e-mails discussing ITER and fusion terminology. He was one of the three fusion experts that year who provided me with the difficult-to-obtain facts about the ITER input power requirements. My publication of that information in October 2017 has led to many corrections on the ITER organization’s Web site, the EUROfusion Web site and several others.

The published statements — and recent corrections — are about the required input power for experimental fusion reactors. Until October 2017, these values were omitted from public communications about these reactors and amounted to a well-kept secret in the fusion community. Readers will have great difficulty finding any references older than one year that reveal the required electrical input power to the Princeton TFTR reactor (950 MW), the JET reactor (700 MW), or the forthcoming ITER reactor (designed to operate with a minimum of 300 MW).

Confusion

In experimental fusion reactors like JET, or the design for ITER, the output thermal power value is easily identified and described; the fusion reactions emit heat and, if captured and converted, this heat theoretically could be used to generate electricity. The input power, however, is not such a simple matter to discuss because there are, in fact, three ways to discuss input values. The transposition of two of these values (explained below), through intentional or unintentional wording, lies at the root of the factual discrepancies given to the public by Cowley, Bigot, and other fusion proponents.

When discussing the power requirements for fusion reactors, Cowley often makes an analogy to a piece of wood burning in a fireplace. But that is a poor analogy. A fireplace is a simple, static chamber. With the exception of the flue, a fireplace has no moving parts. It does not require a constant source of input power.

On the other hand, fusion reactors like JET or ITER are complex devices. In fact, ITER will likely be the most complex mechanical device ever constructed. During operation, ITER will be connected to the power grid and draw up to 620 million Watts of electrical power from hydroelectric and nuclear power plants in southern France. Some of that power will be used to heat the fuel, a mixture of hydrogen gases, while other power will go to the other subsystems required for the ITER device’s operation. These are the three methods to describe the input power for fusion reactors like JET and ITER:

1. Total system electrical power consumed (Including power for the heating systems, magnetic systems, current drive, etc.)

2. Electrical power consumed only by the heating systems (a subset of #1)

3. Thermal power produced by the heating systems and injected into the reaction chamber (a subset of #2)

The distinction between #2 and #3 requires explanation. The reactor chamber needs temperatures in the millions of degrees to induce fusion. In the case of ITER, the heating subsystems will consume about 150 MW of electrical power, and because of conversion inefficiency, only 50 MW of thermal power will be injected into the reaction chamber. But these fusion reactors require multiple subsystems in addition to the heating subsystems. Here are the input power values for each reactor:

ITER (Projected Result)

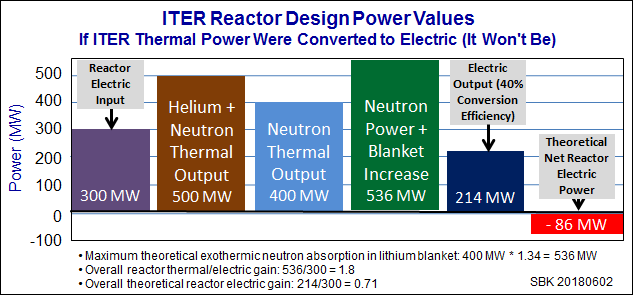

1. Total system electrical power consumed: 300 MW (minimum)

2. Electrical power consumed only by the heating systems: 150 MW (Included in the 300 MW value)

3. Thermal power produced by the heating systems and injected into the reaction chamber: 50 MW (Included in the 150 MW value)

JET (1997 Result)

1. Total system electrical power consumed: 700 MW (minimum)

2. Electrical power consumed only by the heating systems: ~75 MW (Included in the 700 MW value)

3. Thermal power produced by the heating systems and injected into the reaction chamber: 24 MW (Included in the 75 MW value)

The best example of Cowley’s misleading statements is the article he published in the October 2010 issue of Physics World. There was no question about the context of the article or what Cowley’s numbers were supposed to represent. The subtitle of his article began “Despite more than 50 years of effort, today’s nuclear fusion reactors still require more power to run than they can produce.” But Cowley’s numbers were not the correct numbers for the full reactor system. Instead of informing readers that the actual total system electrical power consumed by JET was 700 MW, Cowley twice wrote that the JET reactor required 25 MW of input power to run and that it produced 16 MW of output power:

“JET needed more energy to run than it produced – 25 MW input power to the plasma produced 16 MW of fusion power.” (Cowley)

“JET produced 16 MW of fusion power while being driven by 25 MW of input power.” (Cowley)

This misrepresentation of the facts has been so widespread — and unrecognized — that most science journalists, and therefore members of the public, were misled, as this evidence shows. Fusion scientists like Cowley caused journalists to publish the false idea that JET produced 70 percent of the power it consumed.

In addition, the fusion scientists caused advisers working for the European Commission, European Parliament, the German Bundestag, the International Atomic Energy Agency, the International Energy Agency, the Culham Centre for Fusion Energy, the Commissariat à L’énergie Atomique et aux Énergies Alternatives, FuseNet, the Institut de Radioprotection et de Sûreté Nucléaire, and the European Parliamentary Research Service to publish the false statement that ITER is designed to produce 500 MW of net power or that it will produce 10 times the power it will consume.

Similarly, in Cowley’s 2010 Physics World article, he provided misleading information to readers about the design of ITER: “ITER … is expected to be producing roughly 500 MW of output power from less than 50 MW of input power – a 10-fold amplification, or gain.”

Cowley published the same misleading information in July 2010, in an opinion piece in The Guardian: “ITER will produce about 500MW of fusion power – 10 times the input power.”

ITER, if all goes well, will produce 500 MW of output thermal power — at the expense of 300 of input electrical power.

Cowley made similar comments on July 23, 2009, at the annual TED Global conference, in the city of Oxford, U.K. There, too, he told the people in the audience that JET produced 16 MW of thermal power without informing them that JET consumed 700 MW of electricity. He told the people that ITER would produce 500 MW of thermal power without informing them that it would consume 300 MW of electrical power.

Oxford Martin School Lecture 2017

In November 2017, while holding the posts of acting director of the Oxford Martin School and president of Corpus Christi College, Cowley gave an energy lecture at the Oxford Martin School.

Consistent with his communications from a decade earlier, Cowley told his audience that ITER will make 500 MW of power. As before, he didn’t explain that, to get the 500 MW, the reactor would require and consume at least 300 MW of electrical power.

In the last half-century, more than 100 fusion reactors have preceded ITER. None has produced more power than it consumed. Neither will ITER. As a reactor system, according to its design capacity, ITER will not demonstrate the feasibility of controlled terrestrial energy from fusion processes.

Consistent Inconsistencies

When Cowley left his posts as the head of the Culham Centre for Fusion Energy and chief executive officer of the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority, Ian Chapman took over both positions. Chapman, too, has made factually inconsistent statements about JET to the public.

On Nov. 12, 2017, the U.K. Sunday Times reported that Chapman told the paper that JET generated 16 megawatts of electricity from 25 megawatts of electricity. The first problem is that JET did not “generate” any excess power. Second, as Cowley did, Chapman omitted the 700 MW value and replaced it with the 25 MW value. Third, Chapman claimed the 16 MW output was electric power rather than thermal power.

I contacted Chapman directly by e-mail; he acknowledged the inaccuracy to me and said he had informed Rod Liddle, the journalist who had written the article and had quoted him. Yet no corrections to the article appeared online.

I sent a follow-up e-mail on Nov. 23 to Eleanor Mills, the U.K. Sunday Times editor, Liddle, Nick Holloway, the spokesman for JET, and Chapman. The Sunday Times still made no corrections to the online article. Two weeks later, on Dec. 2, 2017, I informed the U.K. Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and members of the U.K. Parliament Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee about the inaccuracy of Chapman’s statement. The following day, the paper corrected Chapman’s two factual inconsistencies. However, the paper kept Chapman’s misleading statement that JET produced as much power as three or four windmills (wind turbines), and the paper continued to withhold from readers the real amount of power JET consumed.

It was therefore not surprising that, many years earlier, technical writers working for the U.K. Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology had published a brochure on nuclear fusion containing these erroneous statements:

Breakeven: when the total output power equals the total input power. The ratio of these two quantities is known as ‘Q’. Breakeven was demonstrated at the JET experiment in the UK in 1997.

The term “breakeven” has four meanings in the fusion lexicon. The meaning that most members of the public understand, as described in the brochure, is that the total output power of a system equals the total input power of that system. With 700 MW in and 16 MW out, JET didn’t come close to breaking even.

The Gold Standard

Fusion representatives’ statements about JET and ITER have, for at least a decade, caused the news media and government organizations to convey false information to the public. Billions of dollars for fusion research — including for salaries of fusion representatives — have been obtained under false pretenses.

The most recent victims of this illusion were the editors of The Guardian, who, on March 12, 2018, wrote an editorial titled “The Guardian View on Nuclear Fusion: A Moment of Truth.” Scientists, the editors said, have come close to breaking even in fusion research; therefore, the editors encouraged their readers to keep the money flowing for ITER.

“JET hasn’t even managed to break even, energy-wise,” the editors wrote. “Its best-ever result, in 1997, remains the gold standard for fusion power – but it achieved just 16 MW of output for 25 MW of input.”

The “gold standard” for the best-ever fusion output power result has been a lie.