8. ITER Organization Corrects Some of Its False Fusion Claims

Nov. 7, 2017 – By Steven B. Krivit

Return to ITER Power Facts Main Page

In response to the Oct. 6, 2017, New Energy Times report “The ITER Power Amplification Myth,” managers of the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), now under construction in southern France, have corrected some of the false and misleading statements on the organization’s Web site. (List of Corrections)

Representatives of the ITER Council at the June 2017 Meeting (List of Names)The ITER organization had told the public for years that, when complete, the nuclear fusion reactor will produce 500 megawatts (MW) of net power.

Here is an example of the false and misleading claim that, until recently, was published on an ITER Web site page specifically for members of the news media:

“ITER has been designed to produce 500 MW of output power for 50 MW of input power—or ten times the amount of energy put in.” (Archive copy)

That statement, as well as other false and misleading statements on the ITER Web site, has since been corrected.

The ITER organization, however, is still not transparent about its 500 MW claim. In contrast, here is an example of a factual and transparent statement about the ITER design capacity, as published on the Japanese ITER team’s Web site:

“Will ITER make more energy than it consumes? … ITER is about equivalent to a zero (net) power reactor, when the plasma is burning.” (Archive copy)

Based on the expectation that ITER will produce 500 megawatts of net output power, the nations of China, the European Union, India, Japan, Korea, Russia, and the U.S. have already contributed billions of public funding dollars and committed billions more for the project.

This misrepresentation was perpetrated by ITER representatives’ use of the phrase “fusion power.” The public thinks the phrase means one thing while fusion scientists know that the phrase means something completely different. Neither meaning is defined on the ITER Web site. Although fusion representatives from many organizations have used the secondary meaning for decades (See “The Selling of ITER“) to give a false appearance of progress in fusion research, the ITER organization has been the most prominent entity to use and profit from this misleading phrase.

A search, limited to only the English language, shows the following examples of the results of the ITER organization’s misleading claim:

- EUROfusion Web site, JET page: “ITER, which is designed to deliver ten times more power than it consumes” (Archive copy)

- EUROfusion Web site, ITER page: [ITER will] “generate 500 MW fusion power which is equivalent to the capacity of a medium-size power plant.” (Archive copy)

- World Nuclear Association Web site: “ITER is to operate at 500 MW (for at least 400 seconds continuously) with less than 50 MW of input power, a tenfold energy gain.” (Archive copy)

- U.S. Department of Energy, Sept. 26, 2017, press release: “ITER can produce 10 times more power than it consumes.” (Archive copy)

- U.S. ITER organization Fact Sheet: “The typical U.S. home presently uses about 5,000 watts of electricity on a continuous basis. [ITER] is expected to produce 500 million watts.” (Archive copy)

- Princeton University, Oct. 5, 2017, news article: [ITER is] “a massive project that will provide 120 megawatts of power — enough to light up a small city.” (Archive copy)

- Geoff Brumfiel, Scientific American, June 2012: “[ITER] will generate around 500 megawatts of power, 10 times the energy needed to run it.” (Archive copy)

- Daniel Clery, Science, Nov. 19, 2015: “[ITER] is predicted to produce at least 500 megawatts of power from a 50 megawatt input.” (Archive copy)

- Nathaniel Scharping, Discover, March 23, 2016: “ITER is projected to produce 500 MW of power with an input of 50 MW.” (Archive copy)

- Davide Castelvecchi and Jeff Tollefson, Nature, May 26, 2016: “[ITER] is predicted to produce about 500 megawatts of electricity.” (Archive copy)

- Damian Carrington, The Guardian, Oct. 17, 2016: “[ITER will] deliver 500MW of power, about the same as today’s large fission reactors.” (Archive copy)

- Henry Fountain, New York Times, March 27, 2017: “ITER will … produce about 10 times more power than it consumes.” (Archive copy)

- Fraser Cain, Universe Today Web site, May 28, 2017: “For every 10 MW of energy pumped in, [ITER will] generate 100 MW of usable power.” (Archive copy)

- Jing Cao, Bloomberg, June 29, 2017: “[ITER’s] developers say it’ll produce 500 megawatts of power using 50 megawatts to get the reaction going.” (Archive copy)

- Edwin Cartlidge, BBC News, July 11, 2017: “[ITER] is designed to generate 10 times the power that it consumes.” (Archive copy)

- Jason Bardi, Inside Science, July 17, 2017: “[ITER] will produce 500 megawatts of output power but only use 50 megawatts of input power.” (Archive copy)

All the statements above are false. At best, the reactor will produce 200 MW of net thermal power output and demonstrate a gain of 1.6 times the power needed to run it. At worst, the reactor will have a net loss of 100 MW and a negative gain of 0.6 times the power needed to run it.

The director of the ITER organization is Bernard Bigot. He reports to the ITER Council, which comprises representatives from each of the member nations and the European Union. The ITER Council is ultimately responsible for the promotion and overall direction of the ITER organization. The council meets twice a year, and its chairman is Won Namkung. Its next meeting is sometime this month.

Namkung has not responded to requests for the date of the meeting or the identity of the representatives of the council. Instead, New Energy Times located the names and photos of the representatives who attended the June 2017 meeting.

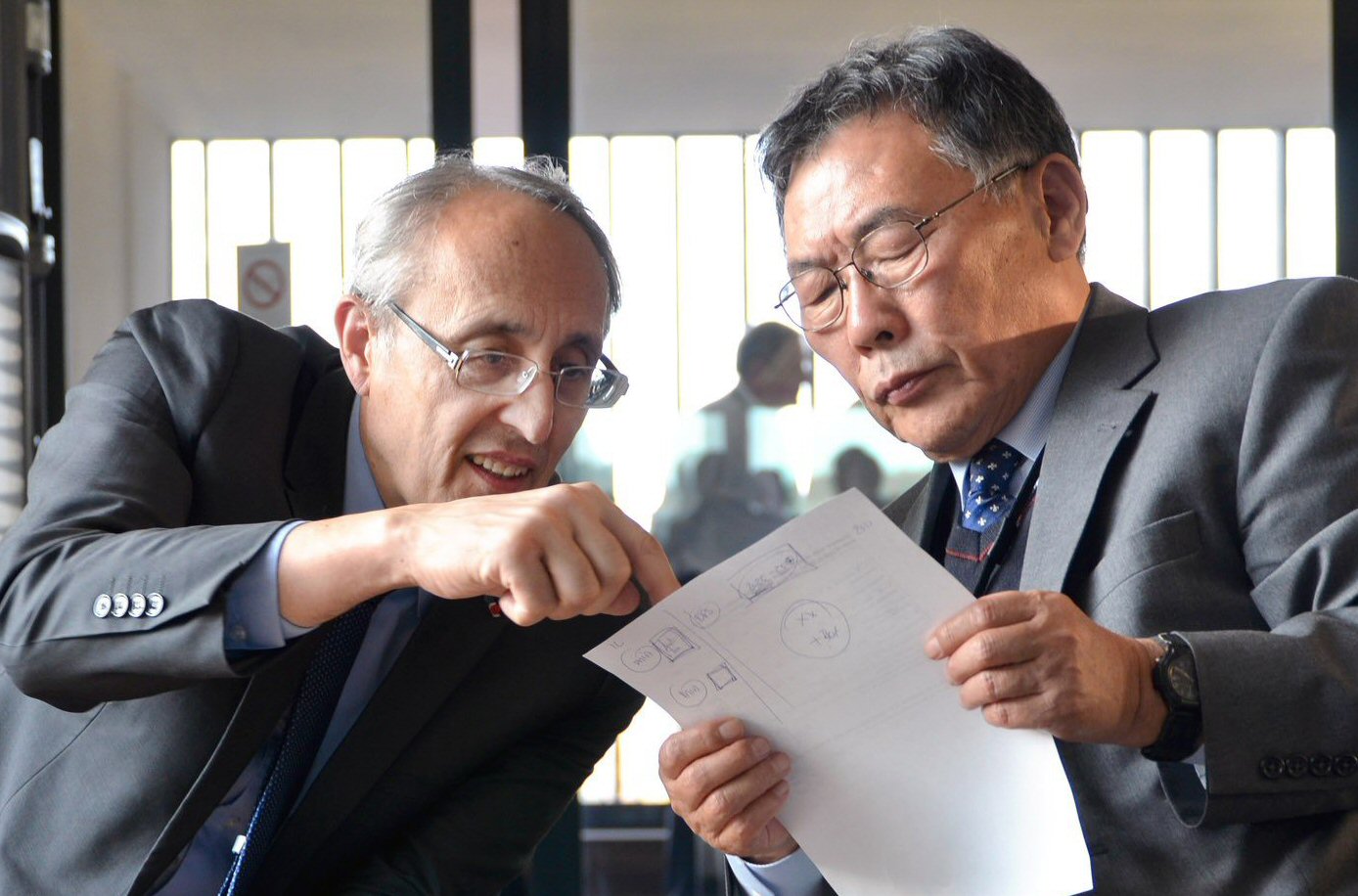

Bernard Bigot, ITER director-general (left); Won Namkung, ITER Council chairman (right)

The ITER fraud was effected not by manipulating the amount of power the machine is expected to produce but by manipulating the perception of the amount of power it will consume. In the history of humankind’s attempts to invent amazing energy-producing machines, hidden sources of power are a common theme.

A well-known story is that of Charles Redheffer. The Redheffer deception ended in 1813 when mechanical engineer Robert Fulton investigated Redheffer’s device, removed wooden boards, and found a concealed rope. Fulton followed the rope upstairs to find an old man sitting quietly on a chair. With one hand, the man turned a crank that was attached to the rope, which sent the hidden power to the device. With the other hand, the man was eating a piece of bread.