Nikkei Reports Mitsubishi to Use LENRs To Clean Nuclear Waste

April 24, 2014 – By Steven B. Krivit –

On April 8, 2014, Nikkei, the Japanese equivalent of the Wall Street Journal, reported that Mitsubishi Heavy Industries in Yokohama, Japan, plans to use low-energy nuclear reactions to clean nuclear waste. This patented LENR transmutation method was developed by Mitsubishi physicist Yasuhiro Iwamura.

New Energy Times has translated the Nikkei story below. We have also placed online a copy of a recent slide presentation from Iwamura and an updated European patent specification from the company.

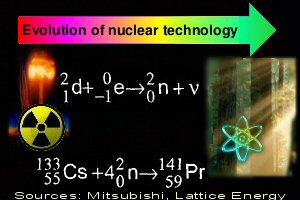

The patent claims that the reactions occur not by fission or fusion, but by a two-step mechanism beginning with a weak interaction; a neutron is created and is followed by a neutron capture process. (Click here to see a related mechanism.)

[DAP errMsgTemplate=”” isLoggedIn=”N”]

Login or Subscribe to remove this notice

Professional Journalism – LENR Facts

Original online content only at New Energy Times

[/DAP]

Source: Nikkei

The Road to Remediation of Radioactive Waste? Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Proceeds Toward Practical Research

April 8, 2014

By Yoshikazu Miura, Business news department

Translated by New Energy Times

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries has established technology based on a low-energy nuclear reaction concept of the transmutation of elements. For example, the transmutation of cesium was experimentally confirmed to increase, by an atomic number of four, to praseodymium, without the use of a large-scale nuclear reactor or accelerator.

The company is moving from a fundamental research stage into a practical research stage. Their technology may open the path to clean nuclear transmutation technology. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, a primary manufacturer of nuclear technology, is eager to use the technology in a practical application to convert radioactive strontium and cesium waste into harmless non-radioactive elements.

Yasuhiro Iwamura and Takehiko Itoh of the Advanced Technology Research Center of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. working on elemental conversion experiments in a clean room. (Photo: Nikkei)

Conversion of Elements Takes Place in a Hundred Hours

In late March, in a lecture room at [but not sponsored by] the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston, Yasuhiro Iwamura presented his group’s research in front of more than 100 researchers gathered from around the world. Iwamura is the leader of the intelligence group at the Advanced Technology Research Center of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd.

[DAP errMsgTemplate=”” isLoggedIn=”N”]

Login or Subscribe to remove this notice

Professional Journalism – LENR Facts

Original online content only at New Energy Times

[/DAP]

“We can confirm the nuclear transmutation of 1 microgram of reaction product,” Iwamura reported. He said that researchers at the meeting asked him many questions about his research and suggested theoretical proposals to explain the group’s results.

Advanced Technology Research Center of Yokohama Mitsubishi Heavy Industries

ATRC is a secretive organization that is engaged in the company’s next-generation research; home to a wide-ranging portfolio of more than 700 products. Researchers wear white protective clothing in the clean room, which takes up about one-third of the first floor of the research building. The researchers set the thin film, about 25 mm square, into the apparatus on a metal plate. Without the use of ultra-high pressure or ultra-high temperature, atomic changes take place within a few days and new elements are created.

The researchers put the source material that they want to convert on top of the multi-layer film, which consists of alternately laminated thin films of calcium oxide and palladium. The thin metal layers have a thickness of several tens of nanometers. Elements are changed in atomic number in increments of 2, 4 and 6 over a hundred hours while deuterium gas is allowed to pass through the film.

The transmutations of cesium into praseodymium, strontium into molybdenum, calcium into titanium, tungsten into platinum have been confirmed. In 2013, Mitsubishi’s patent, originally issued in Japan, was continued in a European patent, and protects their proprietary thin-film transmutation technology.

“Research has greatly accelerated in the last few years,” Takashi Ishide, the general manager of the Advanced Technology Research Center said. By increasing the concentration of deuterium in the various methods, the yield of the newly transmuted elements is increased by three orders of magnitude from nanograms to micrograms. The researchers have also increased the measurement accuracy and confirmed the conversion of elements of a few micrograms from samples of up to 1 cm2 of surface area.

The conversion rate of cesium atoms sometimes comes close to 100 percent. Sometimes they detect low-energy gamma rays during the elemental conversions. The researchers hypothesize that inside the palladium multilayer film, in the case of cesium, four deuterons enter the nucleus and it then becomes praseodymium by the addition of four neutrons and four protons. However, the mechanism is not yet understood and more theory is needed.

Other people have said that the “energy balance does not match, and the reaction can not be explained by the common sense of conventional physics” and elemental conversion. There are also some people who say that “the possibility that contamination from the outside can not be completely ruled out” and that the amount of new elements is too small.

Thin film of multilayer metal substrate that Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. has developed. (Photo: MHI)

Experiments to Elucidate the Unknown Phenomenon

Their transmutation research is based on a related concept of room temperature “cold fusion” as was proposed in 1989. Attempts were made around the world to reproduce “cold fusion” to obtain the dream of fusion without ultra-high temperature of 100 million degrees, however almost all the attempts failed.

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries started their research at that time but t hey thought that it would be easier to demonstrate nuclear transmutation rather than to try to prove the generation of energy, so their work was focused on the conversion of elements. They confirmed the transmutation of trace elements with precise analyses performed at the SPring-8 research center in the Hyogo Prefecture, one of the most trusted research facilities in the world.

Chikashi Nishimura, with the National Institute for Materials Science, who helped the Mitsubishi researchers, said the research “suggests the possibility of element conversion reactions to new species in a way that is not yet understood.”

A research and development company of the Toyota Group, Toyota Central Research and Development Labs (in Aichi Nagakute City), has also replicated the elemental conversion research, and their results seem to be similar.

The Japan “JCF” meeting took place at Tokyo Institute of Technology last December. There, researchers and engineers from all over the country gathered to study the theme of low-temperature nuclear fusion and transmutation. In addition to Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, many university researchers, including professor Shinya Narita of Iwate University School of Engineering, presented their results. Narita says he is continuing the experiments “to advance the elucidation of the unknown phenomenon.”

Akito Arima, the former Minister of the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, visiting the transmutation research group at Mitsubishi Heavy Industries in 2009. (Photo: MHI)

Iwamura obtained a sufficient quantity of new material to be convinced of the elemental conversion. “We don’t understand the theoretical mechanism,” Iwamura said, “but we want to advance to the next step, toward practical applications. The research cannot be denied if we can obtain greater quantities of transmuted elements.”

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries hopes to advance the prospect of practical applications by expanding the scale of the experiment and increasing the yield. It has been studied in the Advanced Technology Research Center only on a small scale so far, but the program has been expanded to include joint experiments with universities, research institutes and other external businesses.

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries is considering experiments that can increase the surface area of the thin-film metal, for example, by using a honeycomb structure. They have not yet started systematic experiments using radioactive elements, but, for example, there is a possibility to convert radioactive cesium-137 into europium.

In addition to processing radioactive waste and production of rare metals, they also hope to use the technology as a possible new energy source. However, the energy and rare metal production applications are highly dependent on economic factors before they can become a practical technology.

“We think it will be possible to put the technologies to practical use within 10 years,” Iwamura said. “Our highest priority is the production of a facility to make radioactive waste harmless because there is no definitive solution for nuclear waste yet.”

The situation has continued under the watchful eye of the press.

Great East Japan Earthquake of Three Years Ago.

An official at Mitsubishi Heavy Industries exclaimed that “if Iwamura’s research was applied to a large-scale facility, it would be possible to convert more elements” and mitigate the spread of radioactive material from the TEPCO Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant.

For more than 20 years, the researchers at Mitsubishi Heavy Industries performed this transmutation research with very limited resources and personnel. “We have continued on a limited budget,” Iwamura said.

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries began the study of the transmutation work in the early 1990s. The group’s research only became widely known in 2002, after Iwamura published a paper in the Japanese Journal of Applied Physics. However, “cold fusion” is viewed as modern alchemy and there is a negative image, so the company was careful about how it appeared publicly.

Iwamura is the manager of about 10 people who are engaged in technical marketing and other research. Iwamura’s title is the leader of the intelligence group in the ATRC technology but his main work is “exploration of technology development trends of other companies which focus on energy and environmental fields.”

In a roundabout way, someone said to Iwamura that he should concentrate on his main work and not deviate by studying the conversion of elements. “I want him to concentrate on his work as a group leader,” the person said. The research budget for nuclear transmutation has been very limited, especially from 2007-2009, when the program was in danger of losing funding.

Along with the knowledge of the elemental transmutation, “the accuracy of the measurements in this research has increased by leaps and bounds over the past decade,” Iwamura said. “University researchers in China are also studying nuclear transmutation using similar equipment as ours.” Iwamura feels that low-energy nuclear transmutation research is now getting recognized more widely.

“If we had started a decade ago,” Iwamura said, “by making a large-scale research system at the time, there is the possibility that now we could have demonstrated specific treatment of radioactive waste. However, the reality is that the science today remains in the basic research stage.”

A senior executive in Mitsubishi Heavy Industries said that the transmutation work at ATRC “is very interesting research.” Another person said that “only a company like Mitsubishi Heavy Industries has the capacity to perform this kind of research because of the depth and complexity of the research.” The person expects to see significant results after 10 years. It’s soon time for the company to decide to invest in the field.

Questions? Comments? Submit a Letter to the Editor.