Forty-Eight Hours in Bologna: The Failure of Rossi’s Energy Catalyzer, Caught on Video

By Steven B. Krivit

Originally Published Jan. 7, 2012

Updated Oct. 28, 2022

On July 30, 2011, Editor Steven B. Krivit, of New Energy Times, published “Report #3,” a 200-page technical analysis of Andrea Rossi’s claimed energy device, which he named the Energy Catalyzer, or E-Cat. Dozens of scientists and engineers from around the world contributed their analyses to that report. They were able to debunk Rossi’s claims from watching what Krivit filmed on June 14, 2011, in Bologna, Italy.

In another article, “The Pied Piper of Bologna: Andrea Rossi’s E-Cat ‘Cold Fusion’ Fraud,” Krivit describes Andrea Rossi’s background, his string of failed energy ventures, and the process by which he collaborated with members of the LENR science community to create an illusion — and a very real $11 million cash payout.

Back to Rossi Investigation Summary

Strange Reports

I started reporting on the energy claims of Andrea Rossi and his device called the Energy Catalyzer, or E-Cat, on Jan. 14, 2011.

Scientists in the low-energy nuclear reaction (LENR) field had been talking excitedly about it for a year. Many of them believed that Rossi had finally demonstrated a commercial-scale LENR reactor. Until then, I had chosen to ignore the chatter.

Rossi had been pumping the Web with bold claims, distributing documents with serious ambiguities, and appearing to offer for sale a dubious energy device. This was unfortunate because the underlying LENR science, indicating a potential new clean-energy source, is valid and credible.

Hours after my first news report, one of my readers in Italy tipped me off to Rossi’s criminal history and one of his previous energy scams. Regardless, prominent scientists in the LENR field were endorsing Rossi’s claims. Mats Lewan, a technology journalist from a Swedish weekly magazine, went to visit Rossi and came away convinced that the power claims for his device were real.

I began an e-mail dialogue with Rossi, and he responded graciously to all my background questions. Rossi had collaborated with Giuseppe Levi, a physicist at the University of Bologna, and I sent some questions to Levi, as well. Eventually, at the request of my philanthropic sponsor, and with Rossi’s agreement, I went to Italy to see for myself.

Red Flags

In the days leading up to my site visit, I began asking Rossi and Levi detailed questions about the experimental design and their data. I asked them the same, normal questions that I had always asked scientists who had made power claims. But they had no answers or data for me. Bad sign. At that point, I had also not been able to get a clear understanding of the device configuration. I asked Rossi for a schematic of his experiment, but he didn’t have one. Another bad sign. I was developing concerns, but I hoped things would clear up once I met with them in person. That didn’t happen.

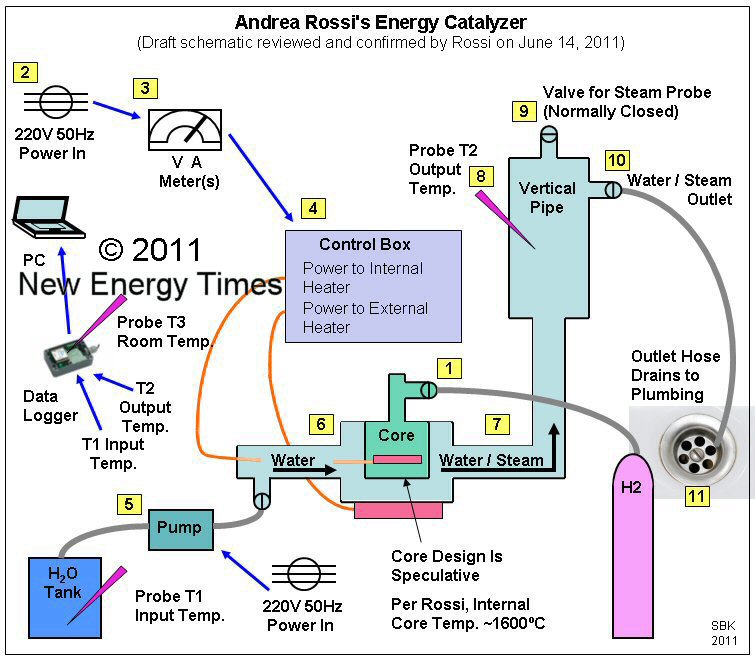

Before I left the U.S., I drew a schematic based on my best understanding of the system at the time. When I met Rossi, one of the first things I did was to ask him to confirm its accuracy. He did, and, in fact, NASA engineers later used my schematic when Rossi came to NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, to entice their interest.

Welcome to My Laboratory!

I arrived at the address Rossi gave me, Dell’Elettricista 6-C, Zona Industriale Roveri, on Tuesday, June 14, 2011, at noon. 6-C was one of the suites in a single-story building that housed a variety of light-industrial companies. The name shown on Suite 6-C was Filli Rossi Pneumatica, which translates to Rossi Brothers Tires.

The large bay door of Suite 6-C was open, and I saw lots of automotive equipment and a few men inside working. I asked a man for Andrea Rossi, and he said I was at the wrong place. He brought me back outside and around to the back of the building.

Two large garage doors opened to reveal a large, nearly empty room, 7,500 square feet in size. The room was barren except for a few dozen folding chairs, folding tables, and a self-standing automated coffee machine.

Rossi greeted me with a friendly handshake and offered me a quick tour of the premises. Inside the large room, situated in a corner, were two smaller rooms. One was a bathroom, and next to that, in a room not much larger than a small bedroom, sat a set of four of Rossi’s devices on top of a sturdy table. Two large tanks of hydrogen stood against the wall. I had been to many laboratories by that time; this was no laboratory.

Sergio Focardi and Rossi’s wife, Maddalena Pascucci

A much smaller room was built inside one corner of the space. Rossi told me it was his laboratory.

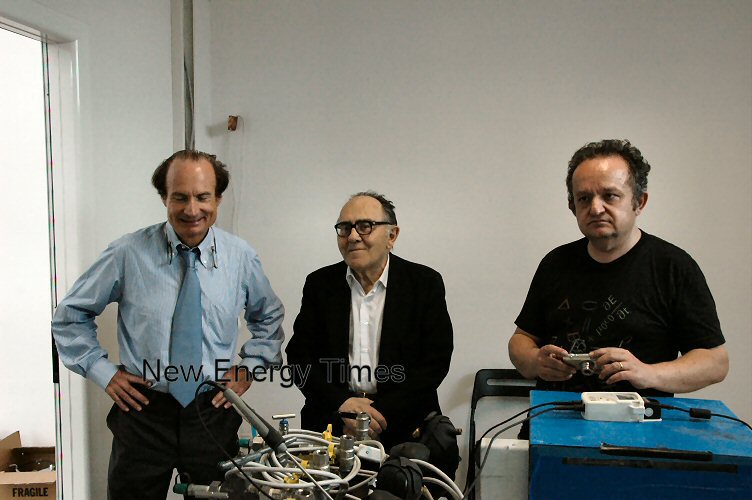

The E-Cat trio: Andrea Rossi, Sergio Focardi, Giuseppe Levi

Four of Rossi’s E-Cat devices. Pay attention to the black hose on the right.

Tools used by Rossi’s plumber to build the E-Cat nuclear reactors

Rossi’s Energy Catalyzer System

Rossi’s Energy Catalyzer System

Rossi’s device consisted of a few small copper pipes soldered to each other, about two feet in length. Water was pumped in from one side and — allegedly — it became fully vaporized and steam came out the other side, into a tall or short vertical pipe, and then out through a black hose. The black hose went to a plumbing drain in the next room. On the inside and outside of the core of the device, Rossi had placed electric heaters to activate a secret nickel-powder-based catalyst.

Rossi said his secret catalyst was heating the water much more than was possible by the electrical heaters alone. He said it was turning all the water into steam. According to his measurements, he put in 770 watts of electrical power. He said that he produced a thermal output of 4,900 watts. The evidence for his power gain, he said, was that all the water was vaporized into steam, which is ordinarily a straightforward power calculation.

I did not figure out that Rossi’s device was specifically designed to send unvaporized water down the drain, thus invalidating his power claim. My readers figured this out. Until I went to see Rossi and his device for myself, nobody had seemed to notice or discuss the absence of visible steam or raise questions about the black hose going into the plumbing drain.

Theoretical Physicist vs. Mechanical Engineer

One of my readers, an Italian mechanical engineer gave me a tip after learning I was heading to Italy. He told me that water expands volumetrically 1,600 times when it turns to steam. He told me that, when I got to Rossi’s lab, I should specifically look for this. He said, “Imagine you’re driving on the highway at 60 miles per hour and you put your hand out to feel the wind. That’s how strongly the steam should be coming out of the output hose.”

Hey! Where’s the Steam?

The first thing I noticed when Rossi demonstrated his device to me is that no steam was coming out of the device. I saw no plume of steam rising dramatically out of the device, as had been visualized and depicted by some of Rossi’s fans. Instead, to my amazement, no visible steam was coming from the device at all. I contained my amazement and continued filming.

During the demonstration, Rossi eagerly showed me the physical components of the device. He showed me the water input and described how it flowed from a jug on the floor into the device. He volunteered to show me the power input meter. On my request, he immediately opened the cover to a large blue electronic control box and encouraged me to look and film inside.

He did not volunteer to show me the most important thing: the steam output or any steam measurements. In fact, I had to ask him three times. I saw that Rossi had a black hose hooked up to the output of the device; it ran into the next room and down a hole in the wall.

Here’s what happened next: Rossi decided that he had shown me everything important about the device, and he started to talk about the energy calculation. I interrupted him. I told Rossi, “Let’s talk about the hydrogen — and then the output.” This was my first request to see steam output. Rossi explained the process of filling hydrogen from the tanks into device.

When he was done explaining the hydrogen, he stumbled with his words; he wasn’t sure what he wanted to discuss next. I reminded him: “Let’s talk about the heat output.”

This was my second request to see steam output. For the second time, however, Rossi explained the water input. Eventually, he got around to explaining the black hose and the output. Rossi did not volunteer to show me any steam coming out of the device.

He stopped talking and waited for my next question. I reminded him again: “We can see the steam?”

“Yeah, sure,” Rossi said.

He walked into the adjacent room. There were three holes in the wall, two of them covered with metal plates. The holes looked exactly as if they were the hot supply, cold supply, and drain for a sink. The black hose was shoved into the center hole.

Rossi bent down and was about to pick up the hose with his hands but stopped. He said, “Just a moment.”

I didn’t know why he stopped, so I paused the camera. He went into the next room and returned with a cloth in one hand and a sponge in the other hand. Then I understood; he knew he couldn’t put his hands directly on the hot hose.

He grabbed the hose and nervously said, “Just a moment” two more times. Before he pulled the hose out of the wall, he slowly and carefully lifted a drooping section of the hose higher than the hole so the water would go down the drain. Rossi pulled the hose out of the wall and showed me the end of it for five seconds and asked, “OK?” He quickly put the hose back in the wall.

No, it was not OK. I couldn’t see or hear any steam flowing. Surely it couldn’t be that bad, I thought. Even if there had been invisible superheated steam jetting out of the hose, I couldn’t hear anything. I paused the camera and asked him if there was a better background we could use to see the steam. Levi was wearing two black T-shirts. He took one off and held it as a backdrop. I start the camera again.

Rossi didn’t want to keep the hose out of drain for a long time. Before pulling it out, he asked me, “Are you ready?”

I said yes, and he pulled it out and held it against Levi’s T-shirt. Now I could see steam coming out: very slowly, in tiny puffs, like a small electric tea kettle on a low setting. The steam was obviously not superheated because it was visible immediately at the exit point of the hose. The exit velocity was so slow that it made no sound.

I immediately suspected that I was observing exactly what the mechanical engineer had told me to look for and that, if this was Rossi’s physical evidence, I had just filmed the evidence of his fraud. I asked Rossi to explain what we were seeing.

“This is steam. And of course, it is not that much visible because it is very hot. Being very hot, it has less density,” Rossi said.

To get the information that I knew engineers would need to confirm Rossi’s power gain claim, I asked Rossi, “So what flow rate is going [in] right now?”

“In this moment, we are making 7 kg of water per hour,” Rossi said. I knew that he meant he was feeding in water at a rate of 7kg per hour.

I talked about and filmed the outlet hose. I knew the engineers would need that information, too.

I asked Rossi what else we should discuss or show for the demonstration — in case he had inadvertently omitted any important details.

All of that is in the first video:

The Math

There was nothing else to see, so we walked over to the easel, and he drew out the calculations, step by step, which were supposed to support his claimed power gain. By this point, just by the exit velocity alone, I had enough information to suspect that Rossi was pulling a hoax. However, because I wanted to review the evidence with technical experts before confronting Rossi, I kept my thoughts to myself and did not confront him.

Rossi’s calculations are in the second video:

During that demonstration that I witnessed, Rossi claimed that his device was producing several kilowatts of power. Based on that, 11,200 liters of steam per hour should have been exiting the Energy Catalyzer. Independent engineers, after watching my video footage, calculated that the steam exit velocity should have been between 76 and 137 miles per hour. Instead, my video shows the steam exit velocity close to 10 miles per hour.

Crucially, Lewan, who had seen Rossi’s device first, didn’t seem to know this, despite his physics degree. Neither did the two Swedish physicists, Hanno Essén and Sven Kullander, who had already encouraged the public to embrace Rossi’s device.

Down the Drain?

At the time, Essén was a theoretical physicist at the Royal Institute of Technology as well as the president of the Swedish Skeptics Society, an organization that is supposed to debunk pseudoscience. Essén had told Lewan that he had checked Rossi’s device and that Rossi’s claim was valid. I interviewed Essén on July 8, 2011. Here’s an excerpt of our conversation:

KRIVIT: Are you aware that many people have calculated that the exit speed [of the steam] should be 50 to 100 km/h?

ESSÉN: Sounds like a lot. No, I wasn’t aware of that. There was not a huge water flow going in, so, intuitively, [the inflow] was consistent with the amount of steam coming out.

KRIVIT: People who have made the speed calculations have written that the speed coming out of a 10mm hose of that length should be really fast; it should have [audible] sound and [visible] momentum. It doesn’t seem like you saw anything like that.

ESSÉN: So where did it go then?

KRIVIT: Probably down the hose into the drain.

ESSÉN: Down the drain? There was no drain.

KRIVIT: Where was the hose going when you saw it?

ESSÉN: There was a room [next] door where there was a hole in the wall, and from that point there was a vent going up. Drops could also go down as far as I understood. There was dripping from the hose, and there was steam going up. It was some kind of ventilator.

Anybody with basic plumbing experience would have immediately recognized that the three holes in the wall, just outside the toilet room, were for a sink: hot supply, cold supply, and the drain.

Levi Interview

I conducted interviews with Levi, Focardi, and Rossi when I was there. Levi described to me his experience when he first began to believe Rossi’s claims:

I was feeling as somebody that has arrived on a new island. Imagine you are traveling on a boat and you see an island that was not on the map. And you just traveled, and you are walking on a new island, and the island is almost completely not known, and you want to tell it to everybody. Then you go back and say, “At this coordinate, there is a new island.” And, of course, you have people saying, “Look on the maps; there is not an island there. You are mistaken, you were in the wrong position, and so on.” But I was quite sure of what I have seen.

The only basis on which Rossi and his collaborators claimed as evidence that all of the water was vaporized into steam was the alleged use of a steam-quality measuring instrument. When I was there, no such instrument was present. Therefore, in my interview with Levi, I asked him how the steam quality was measured. He didn’t answer me directly but said that Rossi had a technical report on the steam measurements.

“There was a check made of the steam by a qualified chemist, Galantini,” Levi said. “When you do this kind of measurement, if there is someone who is an expert in one field, in one type of measurement, I will let them do that measurement so that I am sure of the result.”

Levi had simply taken Rossi at his word. When I interviewed Rossi the following day and asked him the same question about how the steam was measured, Rossi said there was no technical report.

Focardi Interview

Before my interview with Focardi, he told me that he wanted Rossi to join us. During the interview, Focardi looked to Rossi to translate my questions into Italian and asked Rossi to translate his answers into English. This was surprising to me because I had never met an Italian scientist who did not speak English. Focardi gave some unclear answers, and he generally appeared confused.

Rossi Interview

In my interview with Rossi, he generally responded to my questions smoothly and with ease, though not necessarily factually. Many of Rossi’s responses were ambiguous. Sometimes, they were inconsistent with his responses to other questions.

The most peculiar part of our dialogue occurred when I asked him about his moment of discovery:

KRIVIT: There must have been some point at which you saw something that you said, “Wow! This is strange.” Do you remember that moment?

ROSSI: Yes, because I burned a finger.

For a Eureka moment, his response was surprisingly simple. I asked him for more details. I have transcribed his exact response:

KRIVIT: Can you tell me more about that moment?

ROSSI: Yes, uhh, because, umm, I was, uh, uh, working with a, with a small reactor which was made of, uh, umm, of copper, was made of copper, uh, and with a small lead shielding, and I was giving energy with a resistance, uh, giving, eh, some sort of temperature. At a certain point, the, the temperature raised very suddenly, and, uh, and I had in my, the, the, uh, left finger of, uh, of, uh, the, the, the, the finger of, umm, uh, the index of my left hand, umm, sit on a, a part of this small reactor which was as big as this, and I burned the top of the finger. That has been the moment when I had the first, let me say, strange result. It was 1997, and I was in the United States.

After conducting hundreds of interviews with scientists in the previous decade, I knew that, if there was one thing any scientist would know clearly and be able to vividly recall, it would be their moment, or moments, of discovery. It’s a story they would have told many times. It was clear to me that he had just made up his response on the spot.

I had never conducted an interview with someone who gave so many responses that were factually inconsistent. Nevertheless, he sat there in front of my camera, for the most part, confidently, with poise and ease. I asked myself what kind of a person was capable of doing this, and I didn’t like the answer.

Return the Coffee Machine

By the end of the interview, I assumed that he knew that I knew that he had fabricated a lot of his answers. I couldn’t wait to get out of there. In fact, I couldn’t wait to get out of Bologna. My train wasn’t for another few hours, but I told him I had to get to the station right away.

Rossi left the building before me. I packed up my gear and waited outside for my ride. Before I left, two men came over from the tire shop next door and took the coffee machine away. There had been no power in the main room, it had been supplied by a long extension cable from the next suite. I remembered that some of the workers from the tire shop had come in while I was filming the interviews to get their cups of coffee. I realized that Rossi had borrowed the coffee machine. This was no laboratory. The show had been staged for my benefit, and it was over.

Trouble Begins

The trouble began when I was waiting for the taxi. Alex Passi, a professor of linguistics at the University of Bologna, walked up to me and asked me for my evaluation of Rossi’s systems. I had met Passi a few weeks earlier. He had helped me translate Rossi’s autobiographical Petroldragon story. Passi also had a long-standing interest in energy innovations and had participated in a panel to evaluate an unrelated energy claim some years earlier.

I began explaining my concerns to Passi. In hindsight, I wish I had not done so.

I told him that the flux of steam coming out appeared to contradict Rossi’s claim of kilowatts of heat production. I told him it looked like a gross exaggeration. Passi’s face became ashen, and he immediately understood the gravity of my concerns. He insisted that I immediately tell Levi. I told Passi that I was reluctant to do so before having a chance to prepare a comprehensive report and speak with experts, particularly with engineers familiar with steam production.

Passi insisted that it would be inconsiderate of me not to immediately tell Levi my concerns. Reluctantly, I agreed. Passi got Levi on the phone, who told him that we would meet him at a restaurant in downtown Bologna.

I had not yet understood the issue of the mixed stream — part water and part steam — coming out of the device, going into black hose and down the drain. All I knew at the time was that the output velocity looked very wrong. This meant that Rossi’s claim of energy gain was bogus. If Rossi had faked it, how had he done it? I had no idea at the moment. The only concern I had heard in advance was something to do with “steam quality.”

Physics on Napkins

Eventually, after Passi and I had received our meals, Levi arrived and sat down with us. Levi appeared annoyed about our disruption to his own lunch. We began discussing physics and drawing on napkins.

As I feared, it did not go well. Levi was taken aback at my suggestion that Rossi’s “steam expert,” a chemist actually, may not have measured the steam correctly. Levi was incensed that I, someone without a degree in physics, would question his judgment and suggest that he had overlooked a fundamental potential source of error.

In Naples

Eventually, Passi dropped me off at the train station, and without any further issues, I caught my train to Naples. There, I was met by several researchers who had been active in LENRs for many years. They were curious about what I had observed in Bologna. We plugged my video camera into their television screen, and they saw for themselves. When it got to the part where the puffs of steam were coming out of the black hose, they all busted out laughing.

The following evening, I published a short news report about my visit in Bologna. It was nothing like the gratuitous news stories that Lewan had been producing. Instead, my preliminary report suggested that there may have been serious faults with the measurements and claims. I made no claims of fraud at that time.

Attacks and Indignation

Within 24 hours, Rossi was no longer the gentleman he had been when I had visited and interviewed him. He responded to fans on his blog by calling me names, making things up about my visit, insisting that the steam measurements had been done properly, and writing that Levi had contacted an attorney. Levi also expressed his indignation and wrote an open letter to me that his friend Daniel Passerini published on his blog on June 17, 2011.

“You insulted me,” Levi wrote, “and my university, trying to say that I’m not knowledgeable enough in my area, tried to scare me and put me under psychological pressure in order to obtain undisclosed data.”

On June 19, 2011, Passi wrote to Levi, and me to try to smooth things out.

“Steven feels that his legitimate questions did not receive strong enough answers,” Passi wrote. “Giuseppe was taken aback by a mode of address which he perceived as aggressive. As a person who has grown up in two cultures, I feel that a lot of what went wrong the other day descends directly from the different ways Americans and Europeans handle potential conflict of opinion in a professional situation. I know that the both two of you are honest and dedicated to your professions. Give this a little bit of time, and try to get all the fuzzy points cleared up, if possible.”

As I later learned, the concerns that I had expressed to Levi about the accuracy of the steam measurements were irrelevant. There was a much bigger problem. Rossi’s “steam expert” could not possibly have measured the steam correctly; he didn’t use an instrument designed to measure steam. The even larger problem, again as I later learned, was that Rossi’s device was designed to allow hidden quantities of unvaporized water to pass from the output of his device, through the black hose, and down into the hole in the wall.

I uploaded the video of Rossi’s device to YouTube. I didn’t tell anybody that I had done so. The character attacks against me and the legal saber-rattling had slightly intimidated me. Yet, within a few weeks, dozens of experts in science and engineering from around the world had found and watched my video. Unsolicited, they began sending me highly detailed scientific and technical analyses. I selected the best from among the contributions and compiled them into a 200-page report that I published on July 30, 2011.

Technical Analyses

In a nutshell, the analyses in our July 30, 2011, report showed that the rate of steam that was coming out of Rossi’s device didn’t match his claim of the production of 5,000 Watts of thermal power. Not by a long shot.

The steam coming out of Rossi’s device looked exactly like what you would expect to see coming out of a 1,000 Watt electric tea kettle on a low setting. And in fact, that’s about how much electricity was going into Rossi’s device.

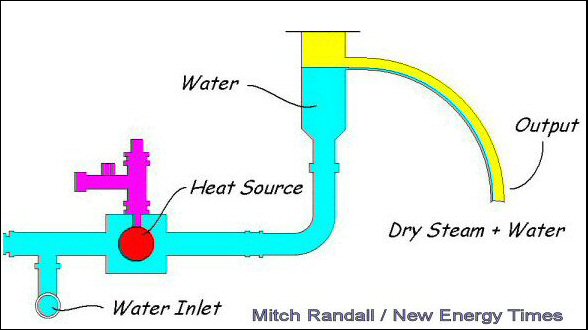

As the diagram below shows, the design of Rossi’s E-Cat provided a simple way for Rossi to hide and send unvaporized water down the drain and thus deceive observers.

Rossi’s E-Cat is designed to conceal and feed unvaporized water down the drain and thus deceive observers who fail to notice the lack of a high flux of steam output. Randall’s diagram indicates water in blue and steam in yellow.

The insights provided by the scientists and engineers who contributed to our Report #3 had significantly resolved the public uncertainty about Rossi’s claim. But Rossi was able to continue keeping hope alive for some of his fans and believers for several years after that. That broader story, including Rossi’s eventual $11 million jackpot, is explained in another article, “The Pied Piper of Bologna: Andrea Rossi’s E-Cat ‘Cold Fusion’ Fraud.”

Fraud

I had seen no evidence of Rossi’s claim of extraordinary levels of thermal power production. Neither Rossi, nor Focardi, nor Levi showed me any scientific data from any experiments that supported their claims. Those facts, combined with the lack of the expected steam flow and the presence of a system to divert unvaporized steam down the drain, led me to conclude that Rossi’s E-Cat claim was fraudulent.