Book Review: Transmutation, The Inside Story

Book Review: Transmutation, The Inside Story

By Steven B. Krivit

June 12, 2020

Tenth in a Series on the Rutherford Nitrogen-to-Oxygen Transmutation Myth

Transmutation, The Inside Story was written by physicist Robin Marshall and self-published on Sept. 12, 2019. The paperback version is 137 pages. (ISBN-10: 107974584X / ISBN-13: 978-1079745849)

Robin Marshall is an emeritus professor of physics from the University of Manchester, recognized science for his research in the field of high-energy physics. Among other awards and honors, he is a Fellow of the Royal Society, was a Fellow of the Institute of Physics, and was awarded the Max Born Medal and Prize by the German Physical Society.

From the back cover: “This is a true story. It is a story of Manchester, discovery and physics, and very little comes truer than that. When the year has a ‘19 in it, you can be sure that Manchester will be at the fore. 1819 was the pinnacle of the ‘19s – Peterloo, when Manchester made sacrifices for the Nation. In 1919, Ernest Rutherford, later Sir, even later Lord, became the planet’s first alchemist.”

I must disclose that this is not an impartial review. In fact, my actions may have precipitated Marshall’s decision to write this book. Before discussing Marshall’s book, some backstory is required for context. In 2014, I was writing my own book, Lost History, which I self-published two years later, in 2016. During research for the book, I identified and described the perpetuation of a 70-year myth that depicted physicist Ernest Rutherford as the world’s first successful alchemist. According to the myth, he performed the experiment which demonstrated the first artificial transmutation of elements, specifically, changing the element nitrogen to oxygen.

In May 2019, I learned that the University of Manchester, in collaboration with the U.K. Institute of Physics History of Physics Group, planned to hold a one-day meeting to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Rutherford’s discovery of the first artificial transmutation of elements. On learning about the meeting, scheduled for June 8, I immediately contacted the organizers and university officials. I informed them that the title and the basis for the meeting were factually incorrect.

According to my investigation, Rutherford’s 1919 papers did not mark his discovery of the first artificial transmutation performed at Manchester. Rather, those papers marked his discovery of the proton, in experiments he performed at Manchester. The credit, I explained to the organizers and university officials, for the first artificial transmutation, actually belonged to Patrick Blackett, when he published, in 1925, experiments he performed at the University of Cambridge.

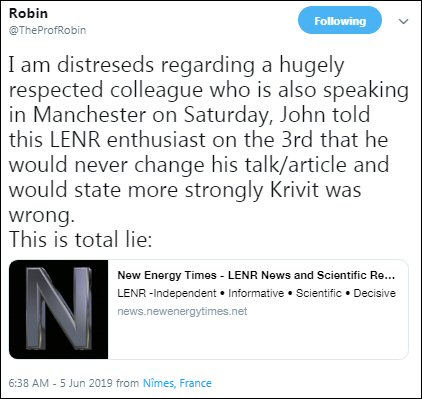

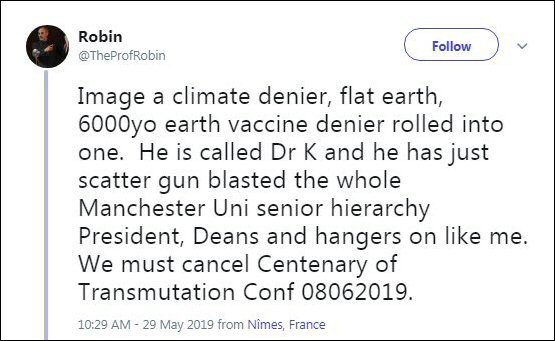

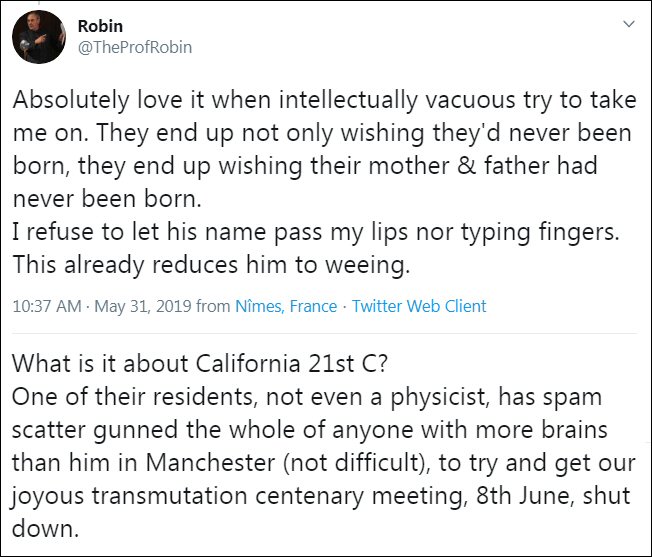

Before the meeting took place, Marshall reacted adversely to my surprising news. He disagreed strongly with my analysis of the history and my conclusion. Marshall took to Twitter to express himself. He promised his readers that the key speaker for the planned meeting, Rutherford expert John Campbell, was going to show that I was wrong. Marshall imagined that I had intended to shut the centenary down rather than encourage the centenary to mark the proper discovery, that of the proton. Marshall’s response was not unique but it was the most extreme reaction that I had encountered. His reaction added drama to what would have been an otherwise dull story about science history.

Three days before the “Centenary of Transmutation” meeting, Marshall wrote on his Twitter account that he was asked to comment and review my “paper.” (Actually, it was not a journal paper but my news article “University of Manchester to Celebrate Wrong Transmutation Discovery.”) He had submitted his review to an unnamed journal in an attempt to show that I was wrong about the discovery credit. Marshall complained on Twitter that the editor had rejected his review, but he was nonetheless determined to triumph. He posted his entire review, as screenshots, to his Twitter feed with exciting preambles to each page.

The “Centenary of Transmutation” meeting took place as scheduled on June 8, 2019, without any change to the title or agenda. Peter Rowlands, a 30-year member of the U.K. Institute of Physics History of Physics Group, opened the meeting with a 38-second introduction and emphatically asserted that the University of Manchester held the bragging rights for the first artificial nuclear transmutation.

“Welcome, ladies and gentlemen, to this celebration of the centenary of transmutation, which took place in this very department 100 years ago,” Rowlands said.

Sean Freeman, the head of the University of Manchester School of Physics and Astronomy spoke next. I had previously been in communication with Freeman. A year earlier, on June 26, 2018, I had written to Freeman and Martin Schröder, the vice-president and dean for the Faculty of Science and Engineering at Manchester. I told them both that a Web page from the physics department depicted the incorrect version of the transmutation discovery. Schröder wrote back to me the following day and, for the most part, expressed his agreement with my findings and conclusions. He thanked me for bringing the error to their attention and, after two rounds of edits, he and Freeman brought the page much closer to the facts as shown by my investigation. (Their page still contains a minor conflation of the historical events.)

After Rowlands’ introduction, Freeman gave his talk — and contradicted Rowlands. Rutherford expert John Campbell followed Freeman. He too, contradicted Rowlands. Freeman and Rowlands discussed many details about Rutherford’s achievements, but neither of them claimed that Rutherford had performed and discovered the first artificial transmutation. Instead, Freeman and Campbell discussed the correct discovery associated with the centenary: Rutherford’s 1919 discovery of the proton.

Sean Freeman speaking at the “Centenary of Transmutation”

Freeman also told the audience that Blackett, at Cambridge, had shown the transmutation of nitrogen to oxygen. In each of their respective chronological narratives, when Freeman and Campbell arrived at the year 1919, they spoke accurately and precisely about Rutherford’s proton discovery.

Marshall had promised his Twitter followers that Campbell was going to “state more strongly Krivit was wrong.” Instead, Campbell said nothing in his talk about Rutherford transmuting nitrogen to oxygen. Instead, Campbell admitted that he was wrong. He said that he had relied on secondary sources that were to blame for his mistake:

“I just assumed that the people writing about Rutherford who knew him were right, but then I’ve found out they never looked at the article — I assumed — records of the day, and just formed their own guesswork.”

John Campbell speaking at the “Centenary of Transmutation”

In the discussion after Campbell’s talk, the audience had a chance to resolve the incongruity between the advertised purpose of the meeting (Rutherford’s transmutation discovery) and the undisclosed revised purpose of the meeting (Rutherford’s proton discovery). Nearly all the audience discussions centered on transmutation. Campbell repeatedly and accurately responded to the audience that, no, Rutherford never claimed that he had transmuted nitrogen to oxygen. In a separate document, I performed a detailed analysis of the meeting discussion and answered some of the audience questions that Campbell did not answer adequately.

A month later, I responded to Marshall’s Twitter-published review in an open letter. I explained how Marshall had misunderstood a fundamental aspect of Rutherford’s experiments.

Marshall thought that when Rutherford discussed oxygen, that it was in the context of experiments performed with nitrogen gas, and that oxygen was the result of a transmutation from nitrogen. Marshall didn’t understand. Rutherford had performed separate experiments; one experiment used nitrogen gas in the chamber, the other experiment used oxygen gas in the chamber. When Rutherford mentioned oxygen in his papers, he was only referring to the similarities of the particle kinetics of experiments performed in the presence of oxygen to the particle kinetics of experiments performed in the presence of nitrogen.

Marshall wrote and self-published Transmutation, The Inside Story as an attempt to prove that the transmutation discovery belonged to Rutherford. Much of his book is anecdotal and contains ancillary aspects to the history. Only a few pages in the book attempt to provide direct support for Marshall’s thesis.

(Page 56): “Rutherford did have transmutation in mind, but kept quiet about it in public until these papers appeared in 1919. He did mention in a personal letter to Bohr in December 1917 that he was trying to do it and asked Bohr to regard it as private.”

Suffice it to say, Marshall provided no direct quote and no citation. Rutherford said no such thing to Bohr, and had no such intention. The actual quotation from Rutherford’s letter, which is quite well known, is this: “I am also trying to break up the atom by this method – Regard this as private.” In that paragraph, Marshall also associated the word transmutation with his own his own phrase “trying to do it.” But that is an inaccurate conflation. Rutherford’s intention was not to transmute one element to another but to break apart the atom so as to learn its structure and develop support for his satellite model of the atom.

(Page 63): “It is significant that he noticed that what should have been nitrogen behaved like oxygen.”

This is, of course, Marshall’s fundamental misunderstanding of the set of experiments, as I already explained in my open letter.

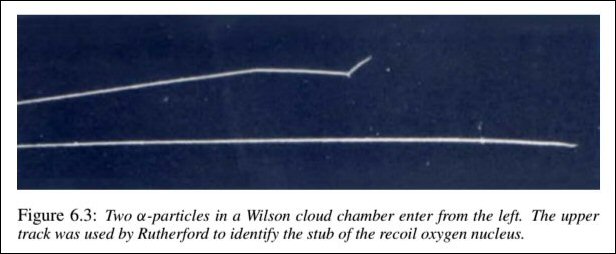

Lower on the page, Marshall traveled further down the road from fact to falsehood. He displayed an image with two particle tracks. Below the image, he wrote this caption:

(Page 63): “Two alpha particles in a Wilson cloud chamber enter from the left. The upper track was used by Rutherford to identify the stub of the recoil oxygen nucleus.”

Again, Marshall provided no direct quote and no citation. In reality, the image Marshall depicts as Figure 6.3 did not come from any of Rutherford’s four 1919 papers. In fact, there are no images of any particle tracks in in any of Rutherford’s set of four papers. Based on my investigation, there is no evidence that Rutherford identified any residual nucleus from his experiments as oxygen before Blackett’s 1925 publication. This image and caption, which Marshall purports to be the primary evidence for his argument, is a complete fabrication.