Open Letter to Dr. Robin Marshall, Emeritus Professor, University of Manchester

July 9, 2019 — By Steven B. Krivit —

Ninth in a Series on the Rutherford Nitrogen-to-Oxygen Transmutation Myth

Dr. Robin Marshall

Emeritus Professor, University of Manchester

Fellow of the U.K. Royal Society

Fellow of the U.K. Institute of Physics

Dear Dr. Marshall,

I am responding to the eight-page comment you posted on your Twitter account about a statement I published in my May 14, 2019, New Energy Times article “The World’s First Successful Alchemist (It Wasn’t Rutherford)“:

According to the myth, Rutherford bombarded nitrogen nuclei with energetic alpha particles and, in doing so, became the world’s first successful alchemist, changing the element nitrogen into the element oxygen.

Marshall-1: “Comments on the Paper by Steven B. Krivit”

The title of your comment is labeled as if I have published an article in a scientific journal. Although I appreciate the generosity of your attribution, the only sentence from me that you have quoted comes from my May 14, 2019, news story. I understand why you wrote the date May 2019 at the top of your first page, but I am puzzled about your including the date “January 2019.”

Marshall-2: “Rutherford bombarded nitrogen nuclei with helium nuclei and observed the production of hydrogen nuclei and noting with surprise that the main recoil nucleus behaved more like oxygen than nitrogen, thereby irrefutably demonstrating nuclear transmutation, changing one element into another and becoming the world’s first successful alchemist.”

I understand your confusion here, and I can help sort it out. You did not provide a citation for your assertion, but from my knowledge of the history, you seem to be referring to this June 1919 statement by Rutherford:

We have drawn attention in Paper III to the rather surprising observation that the range of the nitrogen atoms in air is about the same as the oxygen atoms. (Rutherford, Collisions IV, p. 586, ¶ 1)

When I was listening to the recording of the June 8 University of Manchester “Centenary of Transmutation” meeting, an audience member expressed the same confusion in the discussion after John Campbell’s talk.

The confusion is most easily resolved by looking at the first of Rutherford’s four papers in this series. In these experiments, Rutherford used a variety of gases to be examined in the containing vessel: air, hydrogen, nitrogen — and oxygen. Initially, Rutherford was examining the kinetics of alpha bombardment in the presence of each of these gases. The energetic alpha particle, on impact with each gas in the vessel, set the nuclei of hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen, respectively, into motion. Rutherford identified these faster atoms as swift hydrogen, nitrogen or oxygen atoms, respectively. Here are some excerpts from his papers that illustrate the concept:

On the nucleus theory of atomic structure, it is to be anticipated that the nuclei of light atoms should be set in swift motion by intimate collisions with alpha particles. From consideration of impact, it can be simply shown that, as a result of a head-on collision, an atom of hydrogen should acquire a velocity 1.6 times that of the alpha particle before impact. (Rutherford, Collisions, p. 537, ¶ 1)

In a previous paper (III), we have seen that the number of swift atoms of nitrogen or oxygen produced per unit path by collision with alpha particles is about the same as the corresponding number of H atoms in hydrogen. (Rutherford, Collisions IV, p. 584, ¶ 4)

In his Collisions papers, whenever Rutherford speaks about a “recoil atom,” he is always talking about atoms in each of the examined gases that are set into swift motion by collisions with alpha particles. He is never speaking about a residual atom that would result from a transmutation.

When Rutherford mentions oxygen in his papers, he is mentioning it only in the context — using chemistry terms — of a reactant, not as a product. Using physics terminology, he mentions oxygen only as a target, not as a residual atom. For example:

In the first place, we have seen that the passage of alpha particles through nitrogen and oxygen gives rise to numerous bright scintillations which have a range of about 9 cm. in air. These scintillations have about the range to be expected if they are due to swift N or O atoms … (Rutherford, Collisions IV, p. 581, ¶ 3)

Above, Rutherford is talking about the number of swift (accelerated) atoms of nitrogen or oxygen, when such atoms are impacted by the energetic alpha particle. Rutherford is talking only about kinetics of the reactants that he knows are in the system: either nitrogen or oxygen. He is comparing only the quantity and range of swift nitrogen atoms when the vessel is filled with nitrogen gas and, alternatively, swift oxygen atoms when the vessel is filled with oxygen gas.

To sum up, the only time Rutherford was talking about oxygen in any of these four papers was when he was talking about the swift oxygen atom after it was struck by the energetic alpha particle, when the vessel was filled with oxygen.

Your statement, for which you failed to provide any direct source citation from Rutherford, reflects your mistaken opinion:

According to all known facts, Rutherford bombarded nitrogen nuclei with helium nuclei and observed the production of hydrogen nuclei and noting with surprise that the main recoil nucleus behaved more like oxygen than nitrogen, thereby irrefutably demonstrating nuclear transmutation, changing one element into another and becoming the world’s first successful alchemist.

Rutherford never, in any of his 1919 papers, said anything about nuclei behaving more like oxygen than nitrogen. Your mistaken interpretation of Rutherford’s discussion of oxygen invalidates the foundation of your argument. For the sake of completeness, however, I will proceed through the rest of your comment for additional matters that may be worthwhile to address.

Marshall-3: “One can add that he also showed that the hydrogen nuclei (protons) did not come from the alphas.”

This is not an ancillary finding; this is in fact the substantive finding of his 1919 papers: the experimental discovery and proof of the proton.

Marshall-4: “Rutherford knew what was happening and that he had changed one element into another. That is irrefutable.”

Rutherford was certainly smart enough to suspect that he had changed one element into another. But he didn’t have experimental evidence to support such a radical claim. In his four 1919 papers, therefore, Rutherford said nothing about changing one element into another. And what Rutherford might have thought doesn’t matter. What matters is what he published. And he published nothing in 1919 about changing one element into another. Blackett did — in 1925.

Marshall-5: “He not only recorded the final state nucleus, which was expected to be nitrogen, but he made the ‘surprising observation’ that its range (determined by atomic number and velocity) made it look more like oxygen. … and what appeared to be oxygen. This is transmutation.”

This is the same mistake you made about oxygen, which I explained in Marshall-2.

Marshall-6: “Rutherford made no mention in his paper IV of the fate of the alpha that resulted from what he called the disruption.”

You are mistaken about this matter, as well. He mentioned his presumption about the fate of the alpha in his paper IV:

Considering the enormous intensity of the forces brought into play, it is not so much a matter of surprise that the nitrogen atom should suffer disintegration as that the alpha particle itself escapes disruption into its constituents. (Collisions IV, p. 587, ¶ 1)

Rutherford also stated this clearly in the first of his 1919 Collisions papers:

Taking into account the intense forces brought into play in such collisions, it would not be surprising if the helium nucleus were to break up. No evidence of such a disintegration, however, has been observed, indicating that the helium nucleus must be a very stable structure. (Collisions I, p. 561, ¶ 2)

Additionally, Rutherford’s speculation in 1920 (Bakerian Lecture) that the nitrogen nucleus, after bombardment, lost mass as a result of the emission of a proton, provides further support that Rutherford believed that the alpha particle did not enter the nitrogen nucleus.

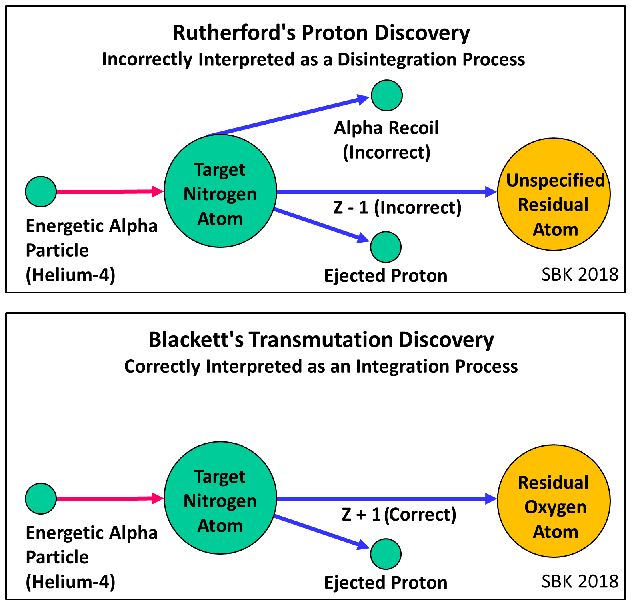

Marshall-7: “The first of Krivit’s diagrams did not happen in the laboratory nor in Rutherford’s head.”

The opposite seems to be true: 1) Rutherford identified the ejected swift hydrogen atom (later called the proton); 2) he did not specify the identity of the residual atom; 3) he wrote that the alpha particle hit the target nitrogen atom and that the alpha particle itself was not broken up: and 4) in his Bakerian Lecture, Rutherford assumed that the alpha particle did not enter the nitrogen atom. This is precisely what my first diagram below clearly shows. I welcome any substantive argument you may offer, and if you can suggest a better diagram, I welcome that, as well.

Marshall-8: “At the 1921 Solvay Conference, Rutherford gave a rapporteur talk, “La Structure De L’ Atome,” reproduced in full in the proceedings in French and surely unread by Krivit. … It shows without a doubt that the international physics community in 1921 talked normally about transmutation. … Perrin in 1921 used the word ‘transmutation’ to describe Rutherford’s discovery, and Krivit simply cannot undo that, 100 years later. The truth is on the record.”

I must disappoint you again. Five years ago, I did locate those proceedings, and I hired a professional to translate them from French to English. The initial insight comes not from Rutherford but from Jean-Baptiste Perrin:

Mr. Rutherford’s experiments seem to prove that we must reject that notion of a simple impact. The alpha projectile, due to its high velocity, and despite a very strong electric repulsion, can reach the immediate vicinity of the nucleus with its speed significantly reduced. At that moment, a “transmutation” takes place, probably consisting of an intranuclear rearrangement with the nucleus’ possible capture of the incident alpha (as we don’t know what becomes of it).

Remember that the previous year, in his Bakerian Lecture, delivered June 3, 1920, Rutherford suggested that a transmutation had occurred, although he did not use that word:

The expulsion of a mass 3 carrying two charges from nitrogen, probably quite independent of the release of the H atom, lowers the nuclear charge by 2 and the mass by 3. The residual atom should thus be an isotope of boron of nuclear charge 5 and mass 11. If an electron escapes as well, there remains an isotope of carbon of mass 11. The expulsion of a mass 3 from oxygen gives rise to a mass 13 of nuclear charge 6, which should be an isotope of carbon. In case of the loss of an electron as well, there remains an isotope of nitrogen of mass 13. The data at present available are quite insufficient to distinguish between these alternatives.

As you know, Rutherford’s guesses in that lecture were wrong. But there’s no reason to fault him for the wrong guesses because he did not have direct experimental evidence with which to illuminate the precise nature of the reaction process or the residual nucleus.

Perrin, not Rutherford, suggested that the process might fundamentally be one of integration rather than disintegration. After hearing what Perrin said, Rutherford agreed with him:

It could very well be that the alpha particle enters into some sort of temporary combination with the nucleus.

Did the international physics community talk about transmutation in 1921? Yes, of course. Did Rutherford suspect at the time that transmutation was occurring? Yes, of course. Did he have direct evidence for the transmutation of one element to another? No. Could he therefore have honestly claimed discovery credit for transmutation? No, he couldn’t do so then; nor can you do so for him retroactively.

Marshall-9: “Marsden is worth quoting. In his talk at the Rutherford Jubilee Conference in Manchester in 1961, he said of Rutherford’s 1919 experiment ‘This was the first observed case of artificial transmutation of atoms.'”

I am well aware that people who were close to and worked with Rutherford, for example Thomas Edward Allibone, were misled. (See my published letter to the editor of the Royal Society.) The fact that Marsden got the history wrong makes this myth even more fascinating.

Marshall-10: “But what does Blackett himself have to say about the situation? Does he give a clue, because I will believe him, a physics Nobel prizewinner, more than Krivit with a business degree. … This dispatches and demolishes Krivit’s main thrust; Blackett also uses the word “disintegration” and gives credit for the discovery to Rutherford.”

You seem to be confused again. As you know, Blackett did not use the word transmutation there. He used the word disintegration, and he was right to do so; it was the word Rutherford had initially used, and it described the process that Rutherford initially assumed. Blackett makes his own discovery quite clear, though he does so with some modesty:

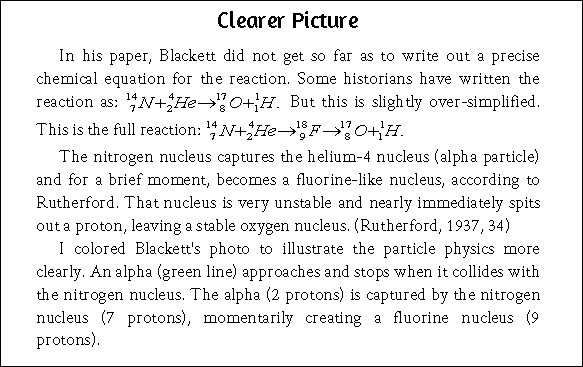

The novel result deduced from these photographs was that the alpha was itself captured by the nitrogen nucleus with the ejection of a hydrogen atom, so producing a new and then-unknown isotope of oxygen, oxygen-17.

Blackett rightfully claimed credit for deducing the process and identifying the residual nucleus.

Marshall-11: “The actual nuclear reaction.”

You have written two pages to show that I did not understand the actual nuclear reaction. Most authoritative sources publish a simplified version of the reaction and skip the intermediate fluorine state. That’s what I did in my news article. In my book, however, published three years ago, I explained the full nuclear reaction, although not in as much detail and not with the technical eloquence you used.

Excerpt from Page 287 of the book Lost History, by Steven B. Krivit

Warm regards,

Steven