Who Started the Ernest Rutherford Transmutation Myth 87 Years Ago?

June 6, 2019 — By Steven B. Krivit —

Sixth in a Series of Articles on the Rutherford Nitrogen-to-Oxygen Transmutation Myth

The myth that the discovery of the first artificial transmutation (nitrogen to oxygen) belonged to Sir Ernest Rutherford was one of the longest-running myths in the history of modern physics. Who caused nearly all physics and science history textbooks written in the last half-century to incorrectly attribute Rutherford as the world’s first successful alchemist? Who caused the Nobel Foundation, countless universities and science institutions to give the credit to Rutherford when it, in fact, belonged to a research fellow working in Rutherford’s Cambridge lab named Patrick Blackett?

Physicist Sir Ernest Rutherford (1871-1937) is a legendary figure in science history. Some people consider Rutherford to be among the 10 greatest physicists in history. Some call him the father of modern physics. The world’s first confirmed artificial transmutation of one element into another has been described by many people as among Rutherford’s three greatest accomplishments. The discovery, however, belonged instead to a research fellow named Patrick Blackett, who worked in Rutherford’s lab at Cambridge University. Although a few historians recorded the discovery correctly, the myth that the discovery belonged to Rutherford was pervasive for 70 years. But how did this myth originate? This article answers that question.

Two Discoveries

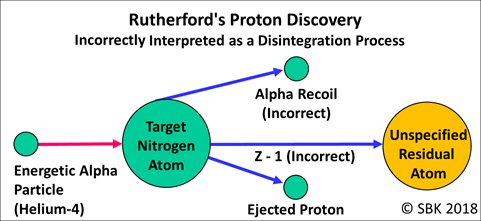

The results of the groundbreaking experiments performed and reported in 1919 by Rutherford are now clear: Protons were emitted as a result of the bombardment of an alpha particle on a target nucleus.

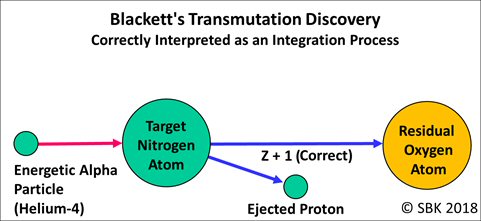

The results of the groundbreaking experiments performed and reported in 1925 by Patrick Blackett are also now clear: The alpha particle was momentarily integrated into the target nucleus and caused the nucleus to increase its atomic number by one, transmuting nitrogen into oxygen, while ejecting a proton.

Unknown Source

The prevalence of the mistaken attribution of the transmutation discovery went back at least to 1948, as shown by a frame in a comic book produced by the General Electric Co. and sponsored by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. However, in September 2018, after I had shown a draft of my first article in this series to Matthew Chalmers, the editor of the CERN Courier, he astutely pointed out that the origin of the myth had to have occurred before 1948.

“As you state,” Chalmers wrote, “Rutherford did not make claims to transmutation in his 1919 papers, nor was that his objective. So when and how did the myth arise? In other words, when was it first shown that it was Blackett, not Rutherford? You reference a 1948 cartoon, but surely the myth had already been established by then? It seems this is an interesting aspect of the story that could offer a rich addition to your draft.”

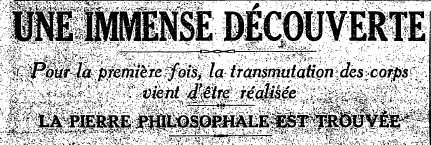

I hadn’t known the answer to Chalmers’ question when I was writing Lost History. I knew that it wasn’t in Rutherford’s set of four “Collision of Alpha Particles With Light Atoms” papers published in June 1919. I had searched the news archives immediately after that date to look for clues. I found nothing until I got to December. On Dec. 8, 1919, Charles Nordmann, writing for the Paris newspaper Le Matin published a Page 1, Column 1 story about Rutherford; apparently, Nordmann thought he had big news.

Headline from Dec. 8, 1919, article in Le Matin: “AN IMMENSE DISCOVERY The Transmutation of Elements Has Just Been Achieved for the First Time”

The article said nothing about any recent news that might have triggered the story. My search revealed no related news at the time or during the previous five months. After I obtained a translation of the article, I learned that the underlying story in Le Matin was only about Rutherford’s bombardment of a nitrogen nucleus and the emission of a proton.

Nordmann had spun the story as a modern-day discovery of alchemy and transmutation: “The transmutation of chemical elements, that old dream that preyed on the mystic minds of alchemists during the Middle Ages, has just been accomplished for the first time.”

But his article included nothing about transmuting nitrogen to oxygen or, for that matter, any element into another. Nordmann had jumped the gun. Nevertheless, this was not the source of the nitrogen-to-oxygen myth. Nor could it have been; Blackett didn’t report the oxygen finding until 1925.

Motivated by Chalmer’s suggestion, I dug deeper and found what appeared to be the original sources of the myth.

1932 Source

One of the few scholars to argue with me about the credit for this transmutation discovery was Karl Grandin, the Nobel Foundation’s science historian. Grandin is the director of the Center for the History of Science at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and the Chair of the History of Physics Group of the European Physical Society. Grandin had told me, among other things, that Rutherford had “reinterpreted” his 1919 results after learning about Blackett’s 1925 results. Something about that word seemed strange. It led me to a search result on a Harvard University Web site: an article written by Rutherford called “Artificial Transmutation of the Elements.” It was a reprint from the McGill News. At my request, Lori Podolsky, an archivist at the McGill University Archives, kindly sent me a copy of the original September 1932 article.

Before I discuss this September 1932 Rutherford article, I need to note a major event in science history that occurred in April 1932: the dawn of high-energy physics. Physicists Ernest Thomas Sinton Walton (1903-1995) and John Douglas Cockcroft (1897-1967) at Cambridge had used an electrical device to accelerate particles; thus, they were able to demonstrate transmutation reactions with much greater ease and efficiency than Blackett had done using the random particles emitted from a radioactive source. For this work, Cockcroft and Walton were awarded a Nobel Prize in 1951 “for their pioneer work on the transmutation of atomic nuclei by artificially accelerated atomic particles.” [1]

Rutherford wrote in his September 1932 article that he was invited by the editor of the McGill News to write a brief statement of the recent work in Cambridge on the transmutation of the elements.

In the article, after Rutherford explained the requirement of swift, high-energy alpha particles to effect atomic transmutation, and under the subheading “Artificial Transmutation,” he began to discuss his 1919 work and Blackett’s 1925 work. Rutherford wrote about himself in third person and began rewriting history:

Rutherford, in 1919, bombarded nitrogen gas with swift alpha particles from radioactive substances and found that high-speed hydrogen nuclei, or free protons as we now term them, were liberated. … This was the first time that definite evidence had been obtained that an atom could be transmuted by artificial methods…

The mechanism of this method of artificial transformation of atomic nuclei was brought out clearly by Blackett, who obtained direct evidence that, in the case of nitrogen, the colliding alpha particle was captured by the nucleus, the disturbance resulting in the ejection of a proton. Since the alpha particle has a mass 4 and charge 2, the nitrogen nucleus, of mass 14 and charge 7, is transformed by the capture of an alpha particle and loss of a proton into a new element of mass 17 and charge 8, in other words into an isotope of oxygen. Subsequently, a stable isotope of oxygen of mass 17 has been found to exist in ordinary oxygen.

Contrary to Rutherford’s statement, he had obtained no “definite evidence” that he had transmuted one element into another, changing nitrogen into oxygen. As Article 2 in this series shows, the only evidence he obtained was that a proton was ejected from the collision of an alpha particle with a nitrogen nucleus.

Blackett didn’t “bring out the mechanism more clearly.” Blackett, in fact, disproved Rutherford’s 1919 hypothesis that the primary mechanism was one of disintegration. Furthermore, to clear up any confusion caused by John Campbell’s article in Physics World this week, Rutherford’s 1932 statement above shows that he suffered no delusion about the transmutation mechanism: Nitrogen had been transformed into oxygen, not hydrogen.

Blackett’s discovery of the transmutation of nitrogen to oxygen never made the news headlines. Therefore, with Rutherford’s new and public reinterpretation of his 13-year-old experiment, assisted by the earlier publicity from journalists like Nordmann, people naturally associated the nitrogen-to-oxygen transmutation with Rutherford, and the myth was born.

1933 Source

The following year, in 1933, Rutherford continued his reconstruction of science history. On October 11, 1933, he gave a lecture, broadcast by the British Broadcasting Corporation, called “The Transmutation of the Atom.” A transcript of the lecture was published in The Scientific Monthly in January 1934. He began by telling listeners that “the possibility of the transmutation of one kind of matter into another has always exerted a strong fascination on the human mind since the early days of science.” He told listeners that, for the past 30 years, he had been actively engaged in investigations in transmutations. Here again, in his 1933 BBC lecture, Rutherford claimed he had made the transmutation discovery:

The first successful experiments in transmutation are comparatively recent, dating back to the year 1919.

Again, he claimed that he performed the experiments with the aim of, and with the achievement of, evidence of transmutation and that Blackett had merely revealed the underlying mechanism:

I made in 1919 some experiments to test whether any evidence of transformation could be obtained when alpha particles were used to bombard matter. … This was the first time that definite evidence was obtained that an atom could be transformed by artificial methods. In the light of later experiments by Blackett, the general mechanism of this transformation became clear.

By 1919, Rutherford had made no experiments to test for and had obtained no evidence of changed elements. That wasn’t his intention. The actual objectives of his 1919 work were a) to resolve the uncertainty of the source of the hydrogen atoms measured by Marsden, b) to throw light on “the character and distribution of forces near the nucleus,” and c) to try to “break up the atom.” Nowhere in his 1919 papers did he express an intention or claim to transmute or transform one element into another.

By 1933, Rutherford could see the immense significance of the transmutation experiments, thanks to Cockcroft and Walton’s newly developed particle accelerator:

My listeners may quite naturally ask why these experiments on transmutation should excite such interest in the scientific world. It is not that the experimenter is searching for a new source of power or the production of rare and costly elements by new methods. The real reason lies deeper and is bound up with the urge and fascination of a search into one of the deepest secrets of nature. Until a few years ago, we had to be content with the knowledge that the whole of matter in the universe, including our own bodies, was made up of 90 or more distinct chemical elements, but we had little definite knowledge of the inner structure of their atoms or of the processes by which one element could be converted into another. Now, for the first time, we are able to investigate these problems by direct experiments in the laboratory, and we are hopeful we shall soon add widely to our knowledge.

1935 Source

In December 1935, the Institution of Electrical Engineers filmed Rutherford giving an overview of the early developments in atomic science. [2] Here is my transcript of the recording:

In our laboratories today, we live in an atmosphere dim with the flying fragments of the exploding atoms. And on this occasion, I wish to say a few words on the methods and ideas employed to break up atoms and to realize, if even on a small scale, the old dream of the alchemists of transmutation of one element into another.

This is a problem in which I have been personally engaged during the greater part of my scientific life, and during this time, I witnessed an astonishing increase of our knowledge. At the close of the 19th century, the labors of the chemists had resolved the matter of our material world into 80 or more distinct elements. And the atoms of these elements appeared to be permanent and indestructible by the forces then at their command.

A great change in their ideas resulted from the discovery of the electron and of the spontaneous radioactivity observed in the heavy elements uranium and thorium. Soddy and I were able to show in 1903 that radioactivity was a sign and measure of the instability of atoms and that the atoms of uranium and thorium were undergoing a series of spontaneous transformations, giving rise to 30 or more new radioactive elements. These elements were ephemeral and broke up according to a definite law, and either a massive alpha particle or a light beta particle was hurled out during the explosion of an atom.

It soon became clear that this property of radioactivity was confined to only a few elements, while a great majority of the ordinary elements seem to be permanently stable over periods of time measured by geological epochs. The next problem was to examine whether means could be found to break up the stable elements by artificial methods. Before this could be attempted with any chance of success, it was necessary to have a clearer conception of the structure of atoms. The idea of the nuclear structure of atoms, which I suggested in 1911, has proved very useful for this purpose.

It became clear that, to effect a veritable transformation of an atom, it was necessary to change the charge or mass of a nucleus or both together. Now, the minute nuclei of atoms are held together by powerful forces, and to effect their disintegration, it seemed likely that a very concentrated source of energy must be applied to the individual atom. The bombardment of the nuclei by the energetic alpha particles from radium appeared to be the most promising method for such a purpose. Acting on these views, I found in 1919 that the nitrogen nuclei could be transformed by bombarding them with swift alpha particles; hydrogen nuclei, or protons, as we now term them, being ejected with high speed as a result of the transformation.

Later, we were able to show that a number of light elements could be transformed in a similar way. Progress in our knowledge of the mechanism of these transformations became more rapid when powerful electric methods were developed to count automatically the swift particles ejected during these nuclear explosions.

It became clear that, to extend our knowledge, a more copious supply of bombarding particles of different kinds was necessary. Charged atoms of various sorts can be produced in vast numbers by the electric discharge through gases and then accelerated by the use of high voltages. In this way, we have been able to obtain through our experiments in transmutation, intense beams of protons and alpha particles, while the discovery of heavy hydrogen has given us a new projectile of remarkable efficiency in transmuting atoms.

By these and other new methods, we were able to break up atoms in a great variety of ways and produce a number of new elements, or rather, isotopes of known elements not observed before. Some of these are found to be unstable and break up according to a definite law like a radioactive element. The discovery in these experiments of neutrons and charged atoms of mass 1 has proved of great significance and importance and has given us a much clearer understanding of the actual structure of nuclei.

This new field of work is now attracting much attention throughout the scientific world, and the progress of our knowledge is very rapid. We are witnessing today the rise of a new department of fundamental knowledge: nuclear chemistry, which is concerned with reactions and changes that may be brought about in the minute world of the atomic nucleus.

Rutherford knew in 1919 that he had changed nitrogen into something else; he just did not know what that was. Without direct evidence of the new element, of course, he made no transmutation claim at that time:

Considering the enormous intensity of the forces brought into play, it is not so much a matter of surprise that the nitrogen atom should suffer disintegration as that the alpha particle itself escapes disruption into its constituents. (Collisions IV, p. 587, ¶ 1)

In his Bakerian lecture, delivered June 3, 1920, he made some guesses, wrong guesses, about the identity of the newly transmuted atom:

The expulsion of a mass 3 carrying two charges from nitrogen, probably quite independent of the release of the H atom, lowers the nuclear charge by 2 and the mass by 3. The residual atom should thus be an isotope of boron of nuclear charge 5 and mass 11. If an electron escapes as well, there remains an isotope of carbon of mass 11. The expulsion of a mass 3 from oxygen gives rise to a mass 13 of nuclear charge 6, which should be an isotope of carbon. In case of the loss of an electron as well, there remains an isotope of nitrogen of mass 13. The data at present available are quite insufficient to distinguish between these alternatives. [3]

Only after Blackett’s 1925 work did Rutherford learn that the residual atom had not decreased in atomic number but increased, becoming oxygen. But in this 1935 video, Rutherford remembered history the way he wanted to: omitting the discovery of the first natural elemental transmutation by chemists Sir William Ramsay and Frederick Soddy and omitting the discovery of the first artificial elemental transmutation by Blackett.

References

1. Cockcroft, J.D.; Walton, E.T.S. (April 30, 1932) “Disintegration of Lithium by Swift Protons,” Nature129(649)

2. Source: Video Recording by the Institution of Electrical Engineers. Video Date: December 1935

3. Rutherford, Ernest (1920) “Nuclear Constitution of Atoms” [Bakerian Lecture], Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 97-A, 374-400; reprinted in The Collected Papers of Lord Rutherford of Nelson O.M., F.R.S. Published under the Scientific Direction of Sir James Chadwick, F.R.S., Chadwick, James, ed., 3, George Allen and Unwin, p. 14-38, (1965)