1. New Energy Times Uncovers Serious Discrepancies in ITER Fusion Facts

By Steven B. Krivit

By Steven B. Krivit

Dec. 14, 2016

Synopsis: Representatives of the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) claim that the world’s largest fusion reactor, when complete, will produce 500 megawatts of thermal energy and that it will produce 10 times more energy than is put in. It will not. In fact, at best, the $21 billion reactor likely will have a zero total net power balance, not 500 MW. Rather than 10 times the power input, the output likely will be equal to the total power input. Based on the same underlying misunderstanding, the 1997 Joint European Torus (JET) fusion experiment, which fusion proponents say achieved 65 percent of break-even, actually came only within 2 percent of total system breakeven.

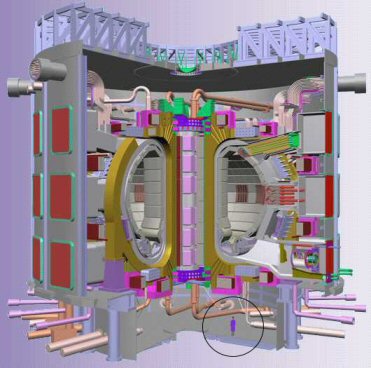

While I was doing research for my book Fusion Fiasco, primarily about the 1989 “cold fusion” fiasco, I came across conflicting information about thermonuclear fusion research that was difficult to believe. This information has a direct and significant impact on the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), under construction now in Cadarache, France.

At an estimated cost of $21 billion, ITER is the most expensive science experiment on Earth. Financial and technical support for the project comes from the European Union, China, India, Japan, South Korea, Russia and the United States. As this article shows, that support has been based on a massive discrepancy between the stated progress of fusion research and the actual progress.

Members of the public and government representatives have agreed to fund ITER based on the hope that the reactor will lead to a source of clean, greenhouse-gas-free energy. Experimentally and theoretically, the principal of thermonuclear fusion is sound. Scientists believe that fusion is the process that powers the sun. The primary challenge in fusion research has been to sufficiently emulate the conditions on the sun. However, creating those conditions on Earth — confining ionized hydrogen isotopes close enough, densely enough, and long enough for a sustained fusion reaction — has been daunting.

For many years, fusion scientists have been enthusiastic about progress they have claimed to make. The primary goal has always been to produce more energy than the fusion reaction consumes, even for just a brief moment. But throughout this time, scientists have been content simply to achieve break-even: getting out as much energy as is consumed.

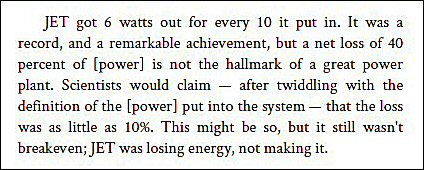

Here’s an example reported by Charles Seife in his book Sun in a Bottle:

Charles Seife, Sun in a Bottle: The Strange History of Fusion and the Science of Wishful Thinking, Penguin Books, 2009

As Seife indicates, the conventional understanding is that JET came 65% of the way to producing as much power as the system consumed. Despite the fact that Seife dedicated his book to critiquing fusion research, he, like every other science journalist, was misled by the fusion promoters’ use of confusing terminology.

In fact, JET did not come anywhere close to making as much power as it consumed. The real fusion power output from JET was only 2 percent of the total system power input.

Here is how this stunning discrepancy and false impression have taken root: Fusion proponents have knowingly perpetuated a misunderstanding between the concepts of system power input and fusion power input. Sometimes, they use the term plasma power instead of fusion power.

System power input is the total power level required to operate all required components of a fusion reactor. Fusion power input is a small subset of system power input; it refers only to the input power required to heat the core of the reactor. Every nonspecialist who has written about fusion has not realized the distinction between the two concepts and has inadvertently misreported these facts.

The typical claim by fusion promoters is that the 1997 experiment at JET set a world record of 16 megawatts of power and that it produced 65 percent of its input power. At face value, one of these numbers cannot be correct. If the experiment produced 16 MW of net power, then the output/input ratio would be greater than 100 percent. In fact, both numbers are gross misrepresentations, and the underlying truth has been hidden simply by omission.

Nick Holloway, the media manager for the Communications Group of the Culham Centre for Fusion Energy, which operates the Joint European Torus, gave me the key facts only when I asked him directly. The total system input power used for JET’s heralded world-record fusion experiment was about 700 MW. (PDF Archive)

Holloway explained that the vast majority of power that goes into the JET reactor goes not to heating the reactor core but to feeding the copper magnetic coils and into other subsystems that are required to operate the reactor. When I interviewed Stephen O. Dean, the director of Fusion Power Associates, a nonprofit research and educational foundation, he concurred.

“The applied fusion power,” Dean wrote, “is not a relevant measure of progress since these have all been experiments not designed for net [power]. The input referred to is just the input to the plasma and does not include the power to operate the equipment.” (PDF Archive)

Thus, a more accurate summary of the most successful thermonuclear fusion experiment is this: With a total input power of ~700 MW, JET produced 16 MW of fusion power, resulting in a net consumption of ~684 MW of power, for a duration of 100 milliseconds.

In other words, the JET tokamak consumed ~98 percent of the total power given to it. The “fusion power” it produced, in heat, was ~2 percent of the total power input.

Now that we understand the distinction between system break-even and fusion (or plasma) break-even, the facts about the ITER power claims become clear.

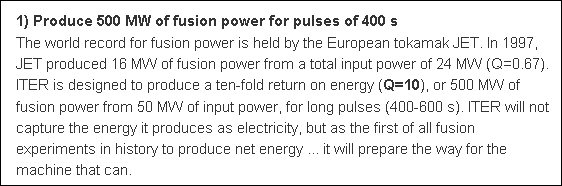

Answer #1 to the question “What will ITER do?” from the official ITER Web site. The value of 24 MW for the total input power is wrong. The correct value is about 700 MW. Source: https://www.iter.org/sci/Goals (Retrieved Dec. 13, 2016)

The values given by fusion proponents to reporters, as shown in the news clippings below, have been widely circulated.

Geoff Brumfiel, “Fusion’s Missing Pieces,” Scientific American, June 2012

Nathaniel Scharping, “Why Nuclear Fusion Is Always 30 Years Away,” Discover Magazine, March 23, 2016

Davide Castelvecchi and Jeff Tollefson, “U.S. Advised to Stick With Troubled Fusion Reactor ITER,” Nature, May 27, 2016

ITER is not likely to produce any excess power, let alone excess energy. It will not generate any electricity. As with the power values for JET, the stated power values for ITER are based only on the ratio of fusion power out to plasma heating power in; the 500 MW value has nothing to do with net system power.

The Japan Atomic Energy Agency Web site is one of the few, if only, fusion organizations to provide honest information: “ITER is about equivalent to a zero (net) power reactor, when the plasma is burning.” (PDF Archive)

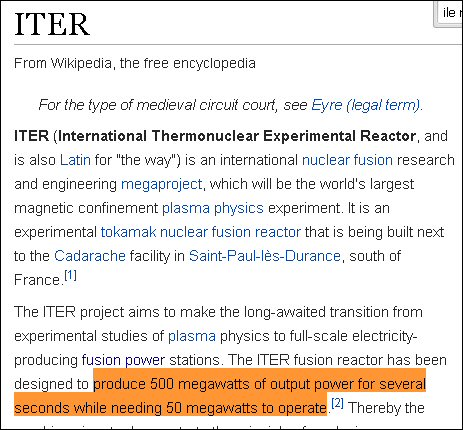

Common misunderstanding of required operating power, as shown in Wikipedia image from Dec. 14, 2016

To perform the largest fusion experiments, ITER must draw electrical input power from a dozen hydroelectric and nuclear fission power plants in the nearby Rhône Valley. The Japanese Web site says that other ITER requirements during the fusion pulses lead to a total steady power consumption of 200 MW during the pulses. The Japanese Web site does not specify any additional power required to prepare for the pulses. But more power requirements are likely.

According to the ITER Web site, the power supply for ITER is planned to have a capacity of up to 620 MW. The total installed power for ITER, according to a technical document, “Power Converters for ITER,” written by Ivone Benfatto, working with the European Fusion Development Agreement in Garching, Germany, will be about 1.8 GVA. All facts indicate that the idea that ITER will consume only a total of 50 MW of electricity to produce 500 MW of heat is erroneous.

ITER will not generate 450 MW of net power output because the reactor will require much more than the 50 MW of electrical input power needed just to heat the plasma. The 50 MW value is the only number for power input that has been disclosed publicly. The actual total input power required to operate the entire ITER reactor system has not been clearly disclosed. However, external power supplied to the reactor from the local grid is planned to have a capacity of 620 MW. Thus, the ITER reactor will not generate 10 times the total power needed to run it.

More details and references are in Chapter 3 of my book Fusion Fiasco.

Dec. 15, 2016 Addendum: As Fusion Fiasco (pages 35-37) shows, testimony from fusion representatives to Congress gave the erroneous impression that JET had produced net power in the millions of Watts. Congress approved funding for ITER based on this misunderstanding. Members of the European Union research commission may have been told a similar erroneous concept. An archived webpage from the official European Union energy research section said that JET had accomplished its mission and that “the scientific and technical basis has now been laid for demonstrating net fusion energy production.”

Dec. 16, 2016, Update: Text has been added to several of the captions.

Note: This article has been edited. The original article contained critical comments about several journalists that were inaccurate.